Abstract

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) is an autosomal dominant disorder that has three major features: multiple neural tumors, café-au-lait spots, and pigmented iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules). The purpose of this case report is to advise physicians of the danger associated with the progression of fast-onset massive hemorrhage to hemodynamic instability, which mandates rapid treatment to prevent the development of a life-threatening condition. A 64-yr-old woman with NF-1 was admitted to the Emergency Department (ED) because of a rapidly growing, 10×5×3 cm-sized mass on the left back area. She had previously undergone surgery for a large subcutaneous hematoma, which had developed on her right back area 30 yr before. She became hemodynamically unstable with hypotension during the next 3 hr after admission to ED. Resuscitation and blood transfusion were done, and the hematoma was surgically removed. The mass presented as a subcutaneous, massive hematoma with pathologic findings of neurofibroma. We report a case of NF-1 that presented as recurrent, massive, subcutaneous hemorrhage on the back region combined with hypovolemic shock.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) is characterized by neurofibromas, pigmented skin lesions (café-au-lait spots), iris hamartomas, and meningeal tumors with a frequency of almost 1 in 3,000 (1, 2). NF-1 is rarely associated with spontaneous hemorrhage. It is thought to be a result of friable vasculature secondary to arterial dysplasia or vascular invasion by the neurofibroma. When bleeding occurs, it is usually from the gastrointestinal tract due to mucosal hypervascular plexiform neurofibroma (2). Massive, life-threatening hemorrhage is rare, and no case of expanding, spontaneous, subcutaneous, recurrent hematoma causing hypovolemic shock has yet been reported. We recommend immediate resuscitation, surgical debridement and hemostasis to improve the survival. We report a patient with subcutaneous hematoma on the left back area assoctated with NF-1, who experienced hypovolemic shock from massive hemorrhage.

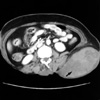

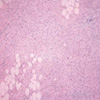

A 62-yr-old woman with known NF-1 was admitted to the Emergency Department (ED) because of a painful and suddenly enlarging mass on the left back area. She had no family history of NF-1. She had a medical history of operation and skin graft of a large hematoma on the right back area 30 yr before, and the biopsy findings were indicative of neurofibroma. On initial physical examination in the ED, the vital signs were blood pressure of 160/90 mmHg, heart rate of 120 beats/min, respiratory rate of 20 breath/min, and an axillary temperature of 36.5℃. On physical examination, there was a soft mass measuring 10×5×3 cm with tenderness on palpation on the left back area. The mass was scarletcolored, non-pulsating, and had a well-demarcated border. Multiple areas of hyperpigmentation (café-au-lait spots) were revealed on her torso and extremities. Axillary frecklings were also revealed. Routine blood samples taken on admission showed a white blood cell count of 11,400/µL, hemoglobin concentration of 12.4g/dL, hematocrit of 37.2%, platelet 244,000/µL, an international normalized ratio of 1.01 (reference range, 0.85-1.30) and a partial thromboplastin time of 29.9 sec (reference range, 29.0-44.0). During the next 3 hr the mass expanded, and the hemoglobin level fell to 8.1 g/dL. At this point, she became hemodynamically unstable with a blood pressure of 73/50 mmHg and a heart rate of 100 beats/min. She was resuscitated with 2.5 L of crystalloid fluid and 1 unit of packed red blood cells and became stable with a blood pressure of 106/60 mmHg. Abdomen and pelvis computed tomography (CT) revealed a huge, subcutaneous, 13×7.6 cm-sized hematoma, along with fluid collection in the posterior and left lateral subcutaneous layer of the thoracolumbar and left lower back area (Fig. 1). Because of the continued expansion of the hematoma and the possibility of hypovolemic shock, she was transferred to the department of chest surgery and underwent emergency surgery to evacuate the hematoma and control the bleeding. On operation, the large hematoma was surrounded with cysts, and many supporting vessels were distributed below the hematoma which oozed blood. Transfusion with a total of 4 units of packed red blood cells and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma was required because of the fall in the hemoglobin level to 1.8 g/dL. Grossly, the tumor was ill-defined, pale yellow, soft, and fibrotic, and it had spread into the fat tissue. Extensive hemorrhage was present on the surface of, but not inside, the tumor (Fig. 2). Microscopically, the tumor was composed of interlacing bundles of elongated cells with wavy nuclei with the fibrillary collagenous background and showed infiltrative growth into the fat tissue consistent with diffuse neurofibroma (Fig. 3). Most of the cells showed a positive reaction for S-100 protein. She was returned to the intensive care unit and remained stable but developed a new hematoma on the operation site without size increase or changes in vital signs and with a steady hemoglobin level of 10.1 g/dL. We presumed that the cause of new hematoma was the residual neurofibroma that could not have been completely removed. During her subsequent hospital stay, she experienced a skin necrosis of 15×10 cm on the operation site, which required debridement and dressing changes twice a day. A skin graft was done on hospital day 21, and she was discharged 50 days after admission.

NF-1 is an inherited disease of the nervous system with a frequency of almost 1 in 4,000. It has no sex predilection and presents in all groups (3, 4). An autosomal dominant inheritance pattern is seen in 50% to 60% of cases; the remaining cases arise as sporadic mutations. The pathogenesis is still uncertain (3). Hemorrhage in NF-1 has been thought to be a result of friable vasculature secondary to arterial dysplasia or vascular invasion by the neurofibroma (1). The neurofibromatous tissue itself also has an abnormal vascular structure with thin-walled ecstatic blood vessels lying in loose neural stroma that replaces the normal adipose tissue (2). Our patient presented with spontaneous, subcutaneous, massive hematoma presumed to have arisen due to bleeding from supporting vessels without evidence of arteriovenous malformation or arteriovenous fistula. NF-1 is further complicated by the possibility of coexisting coagulopathies. Most reported cases have been associated with intrathoracic and gastrointestinal tumors (3). Our patient revealed normal laboratory findings of coagulation. Surgical exploration should be undertaken because fatal hemorrhage is possible if the bleeding is not controlled. There are three key points to reduce the amount of hemorrhage to a minimal level: hypotensive anesthesia, preliminary sutures around the lesion, and ligation of the limited numbers of feeding vessels in the vascular malformation of the neurofibroma (6). Diathermy is of limited use since the tissue is very friable (3). The use of external compression is also recommended to ensure hemostasis. Rapid growth or intratumoral hemorrhage in NF-1 may be an indicator of malignant transformation (5). Patients with large neurofibromas represent a surgical challenge, have a high recurrence rate if tumors are subtotally resected, intense adherence and invasion into tissue, and have a risk of malignant transformation (7). Spontaneous, massive, recurrent hemorrhage in a patient with NF-1 is rare but its early diagnosis to prevent the possibility of progression to hypovolemic shock is essential. Treatment with rapid resuscitation will reduce the life-threatening condition.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Abdomen and pelvis CT showing a huge, subcutaneous, 13×7.6 cm-sized hematoma, along with fluid collection in the posterior and left lateral subcutaneous layer of the thoracolumbar and left lower back area (arrow).

References

1. Rao V, Affifi RA, Ghazarian D. Massive subcutaneous hemorrhage in a chest-wall neurofibroma. Can J Surg. 2000. 43:459–460.

2. Poston GJ, Grace PA, Venn G, Spencer J. Recurrence near-fatal haemorrhage in von Recklinghausen's disease. Br J Clin Pract. 1990. 44:755–756.

3. White N, Gwanmesia I, Akhtar N, Withey SJ. Severe haemorrhage in neurofibroma: a lesson. Br J Plast Surg. 2004. 57:456–457.

4. Restrepo CS, Riascos RF, Hatta AA, Rojas R. Neurofibromatosis type 1 spinal manifestations of a systemic disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005. 29:532–539.

5. Tsutsumi M, Kazekawa K, Tanaka A, Ueno Y, Nomoto Y, Nii K, Haraoka S. Rapid expansion of benign scalp neurofibroma caused by massive intramural hemorrhage. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002. 42:338–340.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download