Abstract

We compared the outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning for the treatment of patients with advanced hematological malignancies. A total of 75 adult patients received transplants from human leukocyte antigen-matched donors, coupled with either reduced intensity (n=40; fludarabine/melphalan, 28; fludarabine/cyclophosphamide, 12) or myeloablative conditioning (n=35, busufan/cyclophosphamide). The patients receiving reduced intensity conditioning were elderly, or exhibited contraindications for myeloablative conditioning. Neutrophil and platelet engraftment occurred more rapidly in the reduced intensity group (median, 9 days vs. 18 days in the myeloablative group, p<0.0001; median 12 days vs. 22 days in the myeloablative group, p=0.0001, respectively). Acute graft-versus-host disease (≥grade II) occurred at comparable frequencies in both groups, while the incidence of hepatic veno-occlusive disease was lower in the reduced intensity group (3% vs. 20% in the myeloablative group, p=0.02). The overall 1-yr survival rates of the reduced intensity and myeloablative group patients were 44% and 15%, respectively (p=0.16). The results of present study indicate that patients with advanced hematological malignancies, even the elderly and those with major organ dysfunctions, might benefit from reduced intensity transplantation.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with myeloablative conditioning has previously been used as a treatment for patients who suffer from hematological malignancies. However, this approach involves considerable toxicity, particularly in elderly patients and those exhibiting severe organ dysfunctions. Therefore, reduced intensity conditioning was designed, in order to more safely conduct HSCT on such patients.

The allografts perform two important functions. The first of these functions is the restoration of conditioning-induced cytopenia, and the second is the exertion of an anti-tumor effect, commonly referred to as the graft-versus-malignancy effect (1, 2). A conditioning regimen is known to facilitate the success of HSCT, but this does not appear to be crucial. In some situations, the ability of HSCT to cure the patient seems to be dependent to a greater degree on the immunological control of the malignancy by the graft (2). Several investigators have reported comparable results for reduced intensity and myeloablative transplantations in the treatment of patients suffering from hematological malignancies of diverse disease status (3-8). Reduced intensity conditioning depends on graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effects for the eradication of malignant cells. When the intensity of conditioning is reduced, a loss of control of the malignant cells might become apparent in the early period after transplantation. If this is, indeed, the case, reduced intensity transplantation may be difficult to perform on patients with advanced hematological malignancies. Therefore, we have conducted a direct comparison of the outcomes of reduced intensity and myeloablative transplantation in the treatment of patients exhibiting advanced hematological malignancies.

We compared the outcomes of allogeneic HSCT using reduced intensity or myeloablative conditioning for the treatment of patients with advanced hematological malignancies. Between January 2001 and December 2004, 75 adult patients, all of whom exhibited advanced hematological malignancies, received transplantations from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched donors, either related or unrelated, coupled with myeloablative (n=40) or reduced intensity (n=35) conditioning, at the Seoul National University Hospital in Korea. Advanced hematological malignancies were defined as follows: acute leukemia beyond 1st remission, chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) beyond 1st chronic phase (CP), refractory Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), and refractory multiple myeloma (MM) that had progressed after autologous HSCT. A full explanation of the transplantation methods was provided to the patients, and informed consent was obtained from all patients who enrolled in the study.

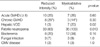

All patients receiving transplantation with reduced intensity conditioning were determined to exhibit contraindications to the myeloablative approach. Contraindications to myeloablative conditioning included advanced age, prior HSCT, major organ dysfunction, or an ECOG performance status of ≥3. The individual reasons for performing reduced intensity HSCT are described in Table 1.

In the reduced intensity group, we used two different fludarabine-based conditioning regimens (Table 2). Among these, the melphalan-containing regimen was used for myeloid malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and CML, and MM. The cyclophosphamide-containing regimen was used for the treatment of lymphoid malignancies (acute lymphoblastic leukemia, NHL) except MM. However, the melphalan-containing regimen was also applied to patients with poor cardiac ejection fractions. Busulfan and cyclophosphamide were used for all of the patients in the myeloablative group.

All patients in the reduced intensity group received cyclosporine (CSP) as a post-transplantation immunosuppressant. CSP was scheduled to be administered at a dosage of 3 mg/kg/day intravenously, or 6 mg/kg/day orally, from days -1 to +30, and then tapered off until day +70 unless the patient developed GVHD. All of the patients in the myeloablative group received four doses of intravenous methotrexate (MTX) combined with CSP (9). The intravenous CSP was replaced by an oral dose in cases in which the patient could tolerate it. The CSP was tapered off and discontinued 6 months after HSCT, contingent on the absence of GVHD. The dosage of CSP was determined on the basis of blood levels in both groups. Acute GVHD was graded from 0 to IV according to the criteria established by Thomas (10), and chronic GVHD was defined and classified according to the Sullivan's criteria (11). In both groups of patients, GVHD treatment normally consisted of methylprednisolone and resumption of CSP, if already tapered.

Supportive cares between the groups were comparable. Prophylaxis against infections was accomplished by the oral administration of ciprofloxacin and fluconazole during the neutropenic period, when the patient's absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was less than 1×109/L. Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim was administered as a prophylactic agent against Pneumocystis jiroveci, after the ANC had risen to a level in excess of 1×109/L. Patients exhibiting chronic GVHD were treated via prolonged sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim prophylaxis.

Means were compared by Student's t-tests. Categorical variables were compared by chi-squared tests. Overall survival and progression-free survival curves were determined using Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimates. Survival curves were compared by log-rank tests, taking the censored data into account. The probability of nonrelapse mortality was calculated using cumulative incidence estimates. Relapse was considered to be a competing risk for nonrelapse mortality. We used the Cox regression model to evaluate the independent effects on survival of several variables. These variables included: type of conditioning, gender of the patient and donor, patient age, type of hematological malignancy, stem cell source, donor source, prior HSCT, and interval between diagnosis and transplantation. All p-values were predicated on likelihood ratio statistics, and were two-sided. Multivariate p-values for a variable reflected the adjustments for all of the other variables in the model. Statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS version 12.0 program (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.).

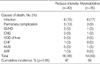

The median follow-up times of the patients with reduced intensity and myeloablative conditionings were 27 and 23 months, respectively. The characteristics of all patients are summarized in Table 3. The median ages of the reduced intensity and myeloablative groups were 50 yr (range, 21-70) and 29 yr (range, 17-49) yr, respectively (p=0.0001). The median ages of the donors for the reduced intensity and myeloablative groups were 46 and 31 yr (p=0.0001). The diagnoses differed slightly between the two groups (p=0.014), as there were more patients with NHL and MM in the reduced intensity group, and also less patients with ALL. The median intervals between the diagnosis and transplantation of the reduced intensity and myeloablative groups were 359 (range, 75-4,328) and 349 (range, 83-4,605) days (p=0.64). Ninety percent of the patients in the reduced intensity group received peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC), as compared with 17% of the myeloablative group patients (p=0.0001). Sixty-eight percent of the reduced intensity group patients and 66% of the myeloablative group patients received transplants from related matched donors (p=0.87). Six of the reduced intensity group patients (15%) had previously received autologous HSCT, and all of them had gone into relapse before being treated via reduced intensity transplantation, whereas none of the myeloablative patients had ever received autologous transplantation (p=0.03). The median cell dose infused for the reduced intensity and myeloablative groups were 5.2×106 CD34+ cells/kg (range, 1.4-25.7×106 CD34+ cells/kg), and 3.3×106 CD34+ cells/ kg (range, 0.9-13.1×106 CD34+ cells/kg), respectively (p=0.003). The median duration of hospital stay for the reduced intensity group patients was 30 days, which was significantly shorter than the 43 days for the myeloablative group patients (p=0.01).

Engraftment failure was detected in 1 patient in the reduced intensity group and 4 patients in the myeloablative group. This was not a significant difference (1/40 vs. 4/35, p=0.18). Neutrophil engraftment (i.e., time to ANC>0.5×109/L) occurred more rapidly in the reduced intensity group (median, 9 days; range, 0-19 days) than in the myeloablative group (median, 18 days; range, 11-38 days) (p<0.0001). The time required to achieve a platelet count in excess of 20×109/L was 12 days (median; range, 7-28 days) in the reduced intensity group, as compared with 22 days (median; range, 9-64 days) in the myeloablative group (p=0.0001).

The incidences of grades II to IV acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) between the reduced intensity and myeloablative groups were comparable, at 25% vs. 26%, respectively (p=0.60). The median day of onset of acute GVHD in the reduced intensity group was day +20 (range 11-35), and also day +20 (range 13-59) in the myeloablative group (p=0.46). The incidence of chronic GVHD among the patients who survived more than 100 days after transplantation was 29% in the reduced intensity group and 14% in the myeloablative group (p=0.30).

Hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD) developed in 1 of the patients (3%) in the reduced intensity group, and 7 patients (20%) in the myeloablative group. These incidences were statistically significant (p=0.02). Febrile neutropenia developed in 33 of the patients (83%) in the reduced intensity group, whereas all of the myeloablative group patients exhibited febrile neutropenia (p=0.01). We noted a trend toward a higher incidence of bacteremia in the myeloablative group (12 patients, 34%), as compared with the reduced intensity group (8 patients, 20%, p=0.16). The frequencies of fungal infection and cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease were similar between the reduced intensity (7% and 3%) and myeloablative groups (9% and 3%). Toxicity profiles are summarized in Table 4.

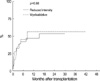

Nonrelapse death and disease recurrence were considered to be competing events for the purposes of this analysis. We detected no difference in the nonrelapse mortality (NRM) of patients receiving reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning. Day-100 and 1-yr NRMs were 33% and 47% for the reduced intensity group patients, as compared with 38% and 56% in the myeloablative patients, respectively (p=0.68, Fig. 1). The causes of NRM did not differ between the groups (Table 5). The most frequently encountered cause of NRM was infection in both the reduced intensity and myeloablative groups (15% and 17%), followed by pulmonary complications and GVHD. Hepatic VOD, as a cause of NRM, was more prevalent in the myeloablative group patients than in the reduced intensity group patients (5% and 0%, p=0.10).

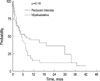

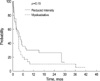

One year overall survival (OS) rates for the reduced intensity and myeloablative groups were 44% and 15%, and the 2-yr rates were 36% and 12%, respectively (p=0.16, Fig. 2). Univariate analysis was conducted using the following factors: conditioning regimen (reduced intensity versus myeloablative), age, stem cell source (PBSC versus bone marrow), donor type (related versus unrelated), prior autologous stem cell transplantation, sex of donor, the interval from diagnosis to transplantation, and diagnosis (acute leukemia and CML versus NHL and MM). None of these factors were found to significantly influence OS. In our multivariate analysis, using Cox regression hazard models, age was determined to be the single significant factor for OS (p=0.01; HR, 1.045; range, 1.011-1.081). We noted a clear trend toward more favorable OS in the reduced intensity group patients. The adjusted hazard ratio of the myeloablative group, as compared to that of the reduced intensity group, with regard to OS, was 2.21 (p=0.09; range, 0.87-5.61). Conditioning type, donor type, and interval from diagnosis to transplantation and disease type were associated with p values of less than 0.1 (Table 6). The proportional hazard assumption was satisfied for all variables in the model. Overall 1-yr progression-free survival (PFS) rates of the reduced intensity and myeloablative group patients were 30% and 10%, respectively (p=0.15, Fig. 3). None of the factors utilized in the univariate and multivariate analyses had any significant influence on PFS.

In this study, we compared the outcome of 40 reduced intensity transplantations with 35 myeloablative transplantations, all of which were conducted at a single institution during the same span of time. Several differences were found between 2 groups. Reduced intensity patients were older and had more major organ dysfunctions than myeloablative patients at the time of transplantation. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation has the potential to cure some of patients with advanced hematological malignancies, but some of the patients, specifically the elderly and those exhibiting severe organ dysfunctions, could not be treated by myeloablative transplantation. Reduced intensity conditioning was developed in order to enable such patients to receive transplants (12-14). Some physicians have raised concerns regarding the possibility of rapid disease progression and resultant treatment failure after reduced intensity transplantation, particularly in patients with advanced hematological malignancies. However, recent reports (3-8) comparing the outcomes of reduced intensity and myeloablative transplantations have obtained results which generally favor reduced intensity transplantation. Our data also support this conclusion. In this study, the 1-yr OS of the reduced intensity and myeloablative groups were 44% and 15%, respectively. Although this is not statistically significant (p=0.16), we noted a clear trend toward higher survival rates for the reduced intensity group. This becomes even more impressive when considering that the patients with reduced intensity conditioning were older, and more frequently exhibited organ dysfunctions, than did the patients with myeloablative conditioning at the time of transplantation.

In this study, we employed two types of fludarabine-based conditioning regimens. One involved melphalan, 180 mg/m2, and the other included cyclophosphamide, 120 mg/kg. The dosages of these drugs (melphalan and cyclophosphamide) were relatively higher than have been used in other fludarabine-based conditioning regimens which included melphalan or cyclophosphamide (8, 15-17). Therefore, the potent anti-malignancy effect associated with the relatively intense reduced intensity conditioning employed in this study might explain the similarities between the PFS rates of the reduced intensity and myeloablative groups in the short-term, and may have also facilitated the establishment of the graft-versus-malignancy effect. Clinical results using identical dosages of melphalan (15) or cyclophosphamide (18) for good-risk patients resulted in PFS rates of 57% and 75%, respectively.

Hematological recovery after reduced intensity transplantation has generally been reported to occur fairly rapidly. According to our results, the median days required for the completion of neutrophil and platelet engraftment were 9 and 12 days, and the engraftment rates were significantly more rapid than those associated with myeloablative transplantation. Such rapid engraftments were reproducibly reported in early studies regarding reduced intensity transplantation (12, 13). In our study, the engraftment failure rate in the reduced intensity group was quite low, comparable to that of the myeloablative group (1/40 vs. 4/35, p=0.18). Reduced intensity conditioning has been known to be associated with a higher risk of engraftment failure than myeloablative conditioning (19). However, the incidence of engraftment failure appears to differ with different reduced intensity conditioning regimens. For example, the administration of fludarabine, combined with 2 Gy of TBI, resulted in a 12% rejection frequency (19). The combination of fludarabine combined with melphalan (8), or the combination of fludarabine with cyclophosphamide (18), as in our study, have tended to report relatively low graft rejection rates.

The development and severity of GVHD has been correlated with cytotoxic tissue injury and the resultant inflammatory cytokine milieu (20). Some investigators have reported lower acute GVHD incidence rates in cases of reduced intensity transplantation (21), while contradictory results also exist (3, 5, 6). The diversity of conditioning regimens, stem cell sources, and GVHD prophylaxis protocols in reduced intensity transplantation might be one reason for this discrepancy. In this study, the incidence of acute GVHD (≥Gr II) in the reduced intensity group (25%) was fairly similar to that of the myeloablative group (26%). The onset of acute GVHD was reported to have been delayed in cases of reduced intensity transplantation, but we noted no differences in acute GVHD onset between our study groups. The single use of CSP as a GVHD prophylaxis and a rapid tapering off of the treatment might explain why we observed no such differences. We also noted a trend toward a higher incidence of chronic GVHD in the reduced intensity transplantation patients (29% vs. 14%). Extant reports also differ (5, 22) with regard to the incidence rates of chronic GVHD in reduced intensity transplantation patients. We believed that higher proportions of PBSC (90% of reduced intensity transplantation) might have explained the higher incidence of chronic GVHD noted in the reduced intensity transplantation group (23).

Most reports, although some exceptions exist, have associated reduced intensity transplantation with less severe infectious complications, especially with regard to bacterial infections (24-27), than are seen in myeloablative transplantation. The lower incidence of infectious complications in reduced intensity transplantation has been explained as follows: i) myeloablative conditioning, which causes an extensive breakdown of mucosal barriers, might result in bacterial translocations within immunocompromised hosts (24, 28), ii) the shorter neutropenic period and prolonged persistence of host immunity after reduced intensity transplantation might also contribute to a lower risk of infection (29). Our study revealed similar results. The incidence of febrile neutropenia (83%) was determined to be significantly lower in the reduced intensity transplantation patients, as compared with the ablative transplantation group (100%). We noted a trend toward a lower incidence of bacteremia in the reduced intensity transplantation group (25%), as compared to the myeloablative transplantation group (43%). However, the degree to which infection contributed to NRM appeared to be similar between the groups (15% and 17%). It is possible that the poor performance status and frequent active infections at the time of transplantation among the patients with reduced intensity conditioning explain, at least in part, the similar infectious death rate between the groups in our study.

The incidence of hepatic VOD in the reduced intensity group was lower than those detected in the myeloablative group, and this difference was significant in our study (3% vs. 20%). In other studies (5, 30), similar results have been reported. Myeloablative conditioning has been associated with harmful cytotoxicity, and appears to result in an inflammatory cytokine milieu around the hepatocytes (31, 32). GVHD prophylaxis containing methotrexate, which was used only in the myeloablative transplantation group in this study, might also have contributed to the higher incidence rates of VOD in the myeloablative group (33).

The cumulative NRM of the reduced intensity and myeloablative transplantation groups were reported to be significantly lower in the reduced intensity group (32% vs. 50% (3) and 16% vs. 30% [5]). However, some investigators have reported similar cumulative NRM incidence rates (4, 6). We detected no differences in the NRM incidence rates between the groups in this study (47% vs. 56%), although our study involved a somewhat higher incidence rate than was reported in previous studies. However, it should be kept in mind that all of the patients in this study had been heavily treated, and were suffering from advanced disease at the time of transplantation. The reduced intensity group patients were all individuals at high risk for NRM (due to old age, poor performance, prior transplantation, recent fungal infections, or major organ dysfunction).

This study clearly has some unique merits. The outcomes of reduced intensity and myeloablative transplantation were determined for the patients treated at a single institution during the same period. Therefore, the so-called 'center effect' and 'time effect', which tend to confound the results of retrospective multicenter or registry studies, had no influence on our results. Also, in our study, the conditioning regimens of the reduced intensity and myeloablative transplantation groups could be assured to be relatively homogeneous.

In conclusion, the results of the current study indicate that patients who suffer from advanced hematological malignancies, even the elderly and those with major organ dysfunctions, might benefit from reduced intensity transplantation. However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, it was a retrospective study. Secondly, the sample size was fairly small. Thirdly, this study did not select for a specific disease type. Therefore, in order to refine applications of allogeneic stem cell transplantation, a large scale randomized clinical trial of reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning will be required.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Cumulative incidences of nonrelapse mortality of patents with advanced hematological malignancies treated by reduced intensity and myeloablative conditionings.

Fig. 2

Overall survivals for patients with advanced hematological malignancies after reduced intensity and myeloablative transplantations.

Fig. 3

Progression free survivals for patients with advanced hematological malignancies after reduced intensity and myeloablative transplantations.

Table 3

Patient characteristics

AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; ABL, acute biphenotypic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; MM, multiple myeloma; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; BM, bone marrow; MRD, matched related donor; URD, unrelated donor.

Table 5

Comparison of the causes of 1-yr nonrelapse mortality for patients receiving either reduced intensity or myeloablative transplants

References

1. Gale RP, Champlin RE. How dose bone marrow transplantation cure leukemia? Lancet. 1984. 2:28–30.

2. Kolb HJ, Schattenberg A, Goldman JM, Hertenstein B, Jacobsen N, Arcese W, Ljungman P, Ferrant A, Verdonck L, Niederwieser D, van Rhee F, Mittermueller J, de Witte T, Holler E, Ansari H. Graft-versus-leukemia effect of donor lymphocyte transfusions in marrow grafted patients. Blood. 1995. 86:2041–2050.

3. Alyea EP, Kim HT, Ho V, Cutler C, Gribben J, DeAngelo DJ, Lee SJ, Windawi S, Ritz J, Stone RM, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ. Comparative outcome of nonmyeloablative and myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients older than 50 years of age. Blood. 2005. 105:1810–1814.

4. Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storer B, Sandmaier BM, Diaconescu R, Flowers C, Maloney DG, Storb R. Comparing morbidity and mortality of HLA-matched unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative and myeloablative conditioning: influence of pretransplantation comorbidities. Blood. 2004. 104:961–968.

5. Diaconescu R, Flowers CR, Storer B, Sorror ML, Maris MB, Maloney DG, Sandmaier BM, Storb R. Morbidity and mortality with nonmyeloablative compared with myeloablative conditioning before hematopoietic cell transplantation from HLA-matched related donors. Blood. 2004. 104:1550–1558.

6. Vela-Ojeda J, Garcia-Ruiz Esparza MA, Tripp-Villanueva F, Ayala-Sanchez M, Delgado-Lamas JL, Garces-Ruiz O, Rubio-Jurado B, Montiel-Cervantes L, Sanchez-Cortes E, Garcia-Chavez J, Xolotl-Castillo M, Rosas-Cabral A, Salazar-Exaire D, Galindo-Rodriguez G, Avina-Zubieta A. Allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation using reduced intensity versus myeloablative conditioning regimens for the treatment of leukemia. Stem Cells Dev. 2004. 13:571–579.

7. Le Blanc K, Remberger M, Uzunel M, Mattsson J, Barkholt L, Ringden O. A comparison of nonmyeloablative and reduced-intensity conditioning for allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2004. 78:1014–1020.

8. Valcarcel D, Martino R, Sureda A, Canals C, Altes A, Briones J, Sanz MA, Parody R, Constans M, Villela SL, Brunet S, Sierra J. Conventional versus reduced-intensity conditioning regimen for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with hematological malignancies. Eur J Haematol. 2005. 74:144–151.

9. Kim I, Park S, Kim BK, Chang HM, Bang SM, Byun JH, Kim DJ, Min WS, Kim HJ, Kim CC. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia: a retrospective study of busulfancytoxan versus total body irradiation-cytoxan as preparative regimen in Koreans. Clin Transplant. 2001. 15:167–172.

10. Thomas ED, Storb R, Clift RA, Fefer A, Johnson L, Neiman PE, Lerner KG, Glucksberg H, Buckner CD. Bone-marrow transplantation (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975. 292:895–902.

11. Sullivan KM. Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease in man. Int J Cell Cloning. 1986. 4:42–93.

12. Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, Kapelushnik Y, Aker M, Cividalli G, Varadi G, Kirschbaum M, Ackerstein A, Samuel S, Amar A, Brautbar C, Ben-Tal O, Eldor A, Or R. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998. 91:756–763.

13. Giralt S, Estey E, Albitar M, van Besien K, Rondon G, Anderlini P, O'Brien S, Khouri I, Gajewski J, Mehra R, Claxton D, Andersson B, Beran M, Przepiorka D, Koller C, Kornblau S, Korbling M, Keating M, Kantarjian H, Champlin R. Engraftment of allogeneic hematopoietic progenitor cells with purine analog-containing chemotherapy: harnessing graft versus leukemia without myeloablative therapy. Blood. 1997. 89:4531–4536.

14. Storb R, Yu C, Wagner JL, Deeg HJ, Nash RA, Kiem HP, Leisenring W, Shulman H. Stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism in DLA-identical littermate dogs given sublethal total body irradiation before and pharmacological immunosuppression after marrow transplantation. Blood. 1997. 89:3048–3054.

15. Giralt S, Thall PF, Khouri I, Wang X, Braunschweig I, Ippolitti C, Claxton D, Donato M, Bruton J, Cohen A, Davis M, Andersson BS, Anderlini P, Gajewski J, Kornblau S, Andreeff M, Przepiorka D, Ueno NT, Molldrem J, Champlin R. Melphalan and purine analog-conditioning preparative regimens: reduced-intensity conditioning for patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing allogeneic progenitor cell transplantation. Blood. 2001. 97:631–637.

16. Ueno NT, Cheng YC, Rondon G, Tannir NM, Gajewski JL, Couriel DR, Hosing C, de Lima MJ, Anderlini P, Khouri IF, Booser DJ, Hortobagyi GN, Pagliaro LC, Jonasch E, Giralt SA, Champlin RE. Rapid induction of complete donor chimerism by the use of a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen composed of fludarabine and melphalan in allogeneic stem cell transplantation for metastatic solid tumors. Blood. 2003. 102:3829–3836.

17. Khouri IF, Keating M, Korbling M, Przepiorka D, Anderlini P, O'Brien S, Giralt S, Ippoliti C, von Wolff B, Gajewski J, Donato M, Claxton D, Ueno N, Andersson B, Gee A, Champlin R. Transplant-lite: induction of graft-versus-malignancy using fludarabine-based nonablative chemotherapy and allogeneic blood progenitor-cell transplantation as treatment for lymphoid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1998. 16:2817–2824.

18. Nakajima H, Oki M, Kishi K, Ueyama J, Miyakoshi S, Hatsumi N, Sakura T, Miyawaki S, Yokota A, Fujisawa S, Mori S, Tanaka Y, Sakamaki H. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide for patients with hematologic malignancies. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003. 25:383–391.

19. Niederwieser D, Maris M, Shizuru JA, Petersdorf E, Hegenbart U, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, Storer B, Lange T, Chauncey T, Deininger M, Ponisch W, Anasetti C, Woolfrey A, Little MT, Blume KG, McSweeney PA, Storb RF. Low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) and fludarabine followed by hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donors and postgrafting immunosuppression with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can induce durable complete chimerism and sustained remissions in patients with hematological diseases. Blood. 2003. 101:1620–1629.

20. Perez-Simon JA, Diez-Campelo M, Martino R, Brunet S, Urbano A, Caballero MD, de Leon A, Valcarcel D, Carreras E, del Canizo MC, Lopez-Fidalgo J, Sierra J, San Miguel JF. Influence of the intensity of the conditioning regimen on the characteristics of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2005. 130:394–403.

21. Parker JE, Shafi T, Pagliuca A, Mijovic A, Devereux S, Potter M, Prentice HG, Garg M, Yin JA, Byrne J, Russell NH, Mufti GJ. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation in the myelodysplastic syndrome: interim results of outcome following reduced-intensity conditioning compared with standard preparative regimens. Br J Haematol. 2002. 119:144–154.

22. Couriel DR, Saliba RM, Giralt S, Khouri I, Andersson B, de Lima M, Hosing C, Anderlini P, Donato M, Cleary K, Gajewski J, Neumann J, Ippoliti C, Rondon G, Cohen A, Champlin R. Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease after ablative and nonmyeloablative conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004. 10:178–185.

23. Cutler C, Giri S, Jeyapalan S, Paniagua D, Viswanathan A, Antin JH. Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic peripheral-blood stem-cell and bone marrow transplantation: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2001. 19:3685–3691.

24. Junghanss C, Marr KA, Carter RA, Sandmaier BM, Maris MB, Maloney DG, Chauncey T, McSweeney PA, Storb R. Incidence and outcome of bacterial and fungal infections following nonmyeloablative compared with myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a matched control study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002. 8:512–520.

25. Busca A, Locatelli F, Barbui A, Ghisetti V, Cirillo D, Serra R, Audisio E, Falda M. Infectious complications following nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2003. 5:132–139.

26. Daly A, McAfee S, Dey B, Colby C, Schulte L, Yeap B, Sackstein R, Tarbell NJ, Sachs D, Sykes M, Spitzer TR. Nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation: infectious complications in 65 recipients of HLA-identical and mismatched transplants. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003. 9:373–382.

27. Meijer E, Dekker AW, Lokhorst HM, Petersen EJ, Nieuwenhuis HK, Verdonck LF. Low incidence of infectious complications after non-myeloablative compared with myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2004. 6:171–178.

28. Filicko J, Lazarus HM, Flomenberg N. Mucosal injury in patients undergoing hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation: new approaches to prophylaxis and treatment. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003. 31:1–10.

29. Maris M, Boeckh M, Storer B, Dawson M, White K, Keng M, Sandmaier B, Maloney D, Storb R, Storek J. Immunologic recovery after hematopoietic cell transplantation with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Exp Hematol. 2003. 31:941–952.

30. Hogan WJ, Maris M, Storer B, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, Schoch HG, Woolfrey AE, Shulman HM, Storb R, McDonald GB. Hepatic injury after nonmyeloablative conditioning followed by allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a study of 193 patients. Blood. 2004. 103:78–84.

31. McDonald GB, Hinds MS, Fisher LD, Schoch HG, Wolford JL, Banaji M, Hardin BJ, Shulman HM, Clift RA. Veno-occlusive disease of the liver and multiorgan failure after bone marrow transplantation: a cohort study of 355 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1993. 118:255–267.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download