Abstract

Although several studies examined factors that influence conscious sedation, investigation was limited into the gender and age. The aim of this prospective study is to identify the clinical variables of successful conscious sedation during gastrointestinal endoscopy. A total of 300 subjects who underwent gastrointestinal endoscopy were enrolled in a prospective fashion. They completed a questionnaire to assess height, weight, drinking, smoking, education level, recent medication, past medical history, previous experience of conscious sedation, preprocedural anxiety, and apprehension about the procedure. Efficacy of sedation and amnesia were evaluated by the subject and the endoscopist. Amnesic and sedative effects were proportionally related with age (p<0.0001). Preprocedural anxiety level was higher in women (p=0.0062), younger subjects (p=0.035), slender subjects (p=0.041), and in those without previous experience of conscious sedation (p=0.0034). This anxiety level was also related to increased pain (p=0.0026) and alertness (p=0.0003) during the procedure. Lower dose of midazolam is needed for sedation in older subjects. Subjects with a high level of preprocedural anxiety such as women, younger subjects, slender subjects, and those without previous experience of conscious sedation should be sedated with great caution because generally, they complain of much more severe pain and alertness during the procedure.

The aim of conscious sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy is to promote the patient's tolerance and cooperation. Thus, the clinical end-points for sedation should aim for amnesia, anxiolysis, and cooperation rather than hypnosis (1). Although propofol provides faster onset and deeper sedation than standard benzodiazepines, clinically important benefits have not been consistently demonstrated in average-risk patients undergoing standard upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy (2). Besides, intravenous midazolam has been proven to give the best results in gastrointestinal endoscopy due to its safety, rapid onset, shorter duration of action, anxiolysis, and amnesia (3). In addition, opiates provide analgesia, produces synergistic sedation with midazolam, and increase amnesia and patient satisfaction (4). Therefore, gastrointestinal endoscopy is still often performed under moderate sedation with benzodiazepine and narcotics.

The use of conscious sedation is widespread presently, and results in a high degree of satisfaction with the procedure by both patients and physician (3, 4). However, there is no well-defined set of practice guidelines that can be used to determine which patients can undergo successful conscious sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy. By determining the predictive clinical variables, patients scheduled for gastrointestinal endoscopic examination will be ensured of the optimal use of sedation. In addition, the identification of clinical variables in conscious sedation would contribute to better satisfaction for both patients and endoscopists. Here, we identified the clinical variables of successful conscious sedation in the Korean population by using multivariate analysis.

This prospective study was conducted in a single health promotion center at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. From November 2002 to February 2003, a total of 300 adult subjects who were scheduled to undergo diagnostic gastrointestinal endoscopy for routine examination were prospectively considered. Because the intention was to sedate, those who prefered not to be sedated were excluded from the study. We also excluded those who had recently taken medications such as benzodiazepines, opioids, barbiturates, and antihistamines because these drugs influence conscious sedation (5). In addition, those who had diagnosed as psychological disease including dementia and those with severe comorbid disease greater than American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) preoperative patient classification III were excluded from the study (6). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Samsung Medical Center, and each study participant signed an informed consent.

Consistent with routine practice, subjects received lidocaine anesthetic spray in a standard fashion. In the endoscopy room, all the subjects had an intravenous access for midazolam 0.07 mg/kg and pethidine 25 mg injection to achieve conscious sedation. After the injection, subjects were monitored for oxygen saturation, heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Each subject underwent standard diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIF-XQ 240, Olympus optical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) with or without sigmoidoscopy (CF 200S, Olympus optical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). In cases with sigmoidoscopy, the subjects ingested Magcorol 250 mL (magnesium carbonate 10.75 g with anhydrous citric acid 19.5 g; Taejoon, Seoul, Korea) 12 hr before the examination. Endoscopic procedure was performed by one of the four attending endoscopists with an endoscopic assistant nurse. Sigmoidoscopy was performed immediately after upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination.

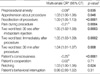

Data collection was completed by the subjects and the endoscopists. Because the adequacy of sedation estimated by the endoscopist does not always correlate with the subjects' own perception, we approached the subject and the endoscopist blindly to each other. Before the application of intravenous midazolam injection, subjects were required to memorize two words, airplane and apple. After the procedure, all of the subjects completed a questionnaire (Table 1-1). Previous experience of conscious sedation (in the questionnaire) included during either the intraabdominal operation or endoscopy.

The efficacy of the sedation was reported by visual analogue scale (VAS) (7). The endoscopist completed a questionnaire about the degree of cooperation (0 extremely poor-100 excellent) and sedation (0 full sedation-100 alert) during the procedure. In addition, the subjects were asked to recall two words which they have heard prior to sedation (Table 1-2). This two word test was performed a total of three times in each subject; 30 sec after midazolam injection, immediately after the procedure, and 30 min after the procedure.

Statistical analyses were done using SPSS software 10.0 and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. The data were reported as mean standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and percentage with 95% confidence interval (CI) for categorical variables. Multivariate analysis was performed with 11 factors (age, gender, body mass index, drinking, smoking, education level, past experience of conscious sedation, type of procedure, total time of procedure, midazolam dose, and biopsy status) to identify clinical predictors of the main outcome (two word test, consciousness, cooperation, retching, behavioral interruption, and pain) as well as preprocedural status (anxiety and apprehension about the procedure). One significant variable (self perceived preprocedural anxiety level) was analyzed by Wilcoxon's two sample test. Spearman's correlation test was used to measure the correlation between two variables expressed as categories.

All 300 subjects completed a questionnaire after the procedure. There was no significant side effect such as oxygen desaturation and life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia. The distribution of subject's variables and procedural variables are summarized in Table 2.

Preprocedural status as assessed by the subject revealed that the degree of preprocedural anxiety level was higher in younger subjects (p=0.035), in slender subjects (p=0.041), in women (Wilcoxon's value=2.74, p=0.0062), and in those without previous history of conscious sedation (Wilcoxon's value=2.96, p=0.030). However, preprocedural anxiety was not related to drinking, smoking, or education level.

Efficacy of the sedation achieved by the endoscopist and the subject are summarized in Table 3. Impact of sedation as assessed by the endoscopist revealed that the degree of consciousness was lower in older subjects (p<0.0001). Degree of amnesia achieved by subjects revealed that older subjects were poor in remembering the procedure (Table 4). In contrast, those who were biopsied during the procedure remembered the procedure much better (p=0.049). In addition, those who underwent sigmoidoscopy with gastroscopy (p=0.032) were relatively alert than those who underwent gastroscopy alone. Slender subjects (p=0.0495) interrupted the procedure more often because of their hyperactive and irritable behavior. Higher preprocedural anxiety level was proportionally related to increased consciousness during the procedure (Table 5). Apart from consciousness, the degree of perceived pain was higher in younger subjects (p=0.0004). Those who revealed a high preprocedural anxiety level complained of much more severe pain (Table 5).

Data from the present study demonstrates that age is the most outstanding factor in conscious sedation. Older subjects generally had a limited understanding of the procedure and showed less anxiety about the procedure. They were easily sedated and exhibited few signs of retching. After the procedure, they complained of little pain and did not remember the procedure compared to younger subjects. This is consistent with a previous study that reports older age is associated with greater patient satisfaction (8). Previous studies reported that midazolam elimination half-life (t1/2) is significantly prolonged in the elderly and midazolam clearance is known to be significantly higher in younger subjects (9, 10). It is also known that, under adequate surveillance, the benefits in terms of tolerance to the procedure of low dose midazolam for gastrointestinal sedation outbalance the risks in older people (11). This means that lower doses of midazolam are needed to reach sedation in older subjects.

The issues of tolerance in conscious sedation appear to deal primarily with anxiety and apprehension. In our study, preprocedural anxiety level was an independent predictive factor for level of sedation and tolerance. Those subjects with high preprocedural anxiety levels complained of much more severe pain and were not easily sedated during the procedure. Females showed higher preprocedural anxiety levels as was reported in a previous study (12, 13). Concerning body mass index, slender subjects were more hyperactive and irritable during the procedure. This might be related with the fact that distribution volume (Vd) of midazolam is significantly increased in obese persons, indicating disproportionate distribution of midazolam into adipose tissue (9). Furthermore, previous experience of conscious sedation was related with lower preprocedural anxiety levels in the present study. It has been shown that individual factors such as personality, prior experience of previous procedures, and the presence of family members influence the level of anxiety and tolerance for endoscopic procedures (14-16). These studies have demonstrated that a higher pre-examination anxiety score and a previous unpleasant endoscopic experience are associated with a reduced tolerance. Although the perception of discomfort and pain may be dependent on cultural characteristics, less anxiety is related to greater patient satisfaction during conscious sedation (8, 17, 18).

The limitation of the present study is that we did not use propofol which recently became popular in conscious sedation. Another limitation is that, apart from gastroscopy examination, we included those patients who underwent both gastroscopy and sigmoidoscopy examinations. These subjects were relatively more alert than those with gastroscopy examinations alone. This result might be related with increased procedural time due to sigmoidoscopy. Furthermore, it can be explained by the fact that lower intestinal endoscopy is associated with greater patient discomfort compared to upper gastroscopy (8).

In conclusion, lower doses of midazolam are needed to reach sedation in the older subjects. Besides, those subjects with high preprocedural anxiety levels such as women, younger subjects, slender subjects, and those without previous experience of conscious sedation, should be observed with great caution because they generally complain of more pain and alertness during the procedure. These factors are predictive of poor tolerance and may enable the identification of the subjects who require more intense conscious sedation.

Figures and Tables

References

1. McCloy R. Asleep on the job: Sedation and monitoring during endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1992. 192:S97–S101.

2. Faigel DO, Baron TH, Goldstein JL, Hirota WK, Jacobson BC, Johanson JF, Leighton JA, Mallery JS, Peterson KA, Waring JP, Fanelli RD, Wheeler-Harbaugh J. Standards Practice Committee. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Guidelines for the use of deep sedation and anesthesia for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002. 56:613–617.

3. Uygur-Bayramicli O, Dabak R, Kuzucuoglu T, Kavakli B. Sedation with intranasal midazolam in adults undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002. 35:133–137.

4. Chokhavatia S, Nguyen L, Williams R, Kao J, Heavner JE. Sedation and analgesia for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993. 88:393–396.

5. Ishiguro T, Ishiguro C, Ishiguro G, Nagawa H. Midazolam sedation for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: Comparison between the states of patients in partial and complete amnesia. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002. 49:438–440.

6. Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL Jr. ASA physical status classifications. Anesthesiology. 1978. 49:239–243.

7. Hong JY, Kang IS, Koong MK, Yoon HJ, Jee YS, Park JW, Park MH. Preoperative anxiety and propofol requirement in conscious sedation for ovum retrieval. J Korean Med Sci. 2003. 18:863–868.

8. Mahajan RJ, Johnson JC, Marshall JB. Predictors of patient cooperation during gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997. 24:220–223.

9. Greenblatt DJ, Abernethy DR, Locniskar A, Harmatz JS, Limjuco RA, Shader RI. Effect of age, gender, and obesity on midazolam kinetics. Anesthesiology. 1984. 61:27–35.

10. Smith MT, Heazlewood V, Eadie MJ, Brophy TO, Tyrer JH. Pharmacokinetics of midazolam in the aged. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1984. 26:381–388.

11. Christe C, Janssens JP, Armenian B, Herrmann F, Vogt N. Midazolam sedation for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in older persons: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000. 48:1398–1403.

12. Levy N, Landmann L, Stermer E, Erdreich M, Beny A, Meisels R. Does a detailed explanation prior to gastroscopy reduce the patient's anxiety? Endoscopy. 1989. 21:263–265.

13. Pereira SP, Hussaini SH, Wilkinson ML. Conscious sedation for gastroscopy. Gastroenterology. 1995. 109:1405–1406.

14. Shapira M, Tamir A. Presence of family member during upper endoscopy. What do patients and escorts think? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996. 22:272–274.

15. Woloshynowych M, Oakley DA, Saunders BP, Williams CB. Psychological aspects of gastrointestinal endoscopy: a review. Endoscopy. 1996. 28:763–767.

16. Drossman DA, Brandt LJ, Sears C, Li Z, Nat J, Bozymski EM. A preliminary study of patients' concerns related to GI endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996. 91:287–291.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download