Abstract

A seven-year-old castrated male Yorkshire terrier dog was presented for a recurrent skin disease. Erythematous skin during the first visit progressed from multiple plaques to patch lesions and exudative erosion in the oral mucosa membrane. Biopsy samples were taken from erythematous skin and were diagnosed with epitheliotropic T cell cutaneous lymphoma by histopathology and immunochemical stain. In serum chemistry, the dog had a hypercalcemia (15.7 mg/dl) and mild increased alkaline phosphatase (417 U/l). Immunohistochemistry was performed to detect parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTH-rP) in epitheliotropic cutaneous lymphoma tissues but the neoplastic cells were not labeled with anti-PTH-rP antibodies. The patient was treated with prednisolone and isotretinoin. However, the dog died unexpectedly.

Malignant lymphoma accounts for 7~24% of all canine neoplasia [6]. Canine epitheliotropic T-cell lymphoma represents only 3~8% of all canine lymphomas [2,8]. It can be subdivided into non-epitheliotropic and epitheliotropic forms [4]. Epitheliotropic cutaneous lymphoma is usually of T cell origin and encompasses a spectrum of disease, including mycosis fungides, Sezary syndrome, and pagetoid reticulosis [5,10,11]. It occurs in old dogs (average age of 9 to 11 years) and has no breed and sex predilection [1]. Four clinical presentations of the disease have been described. Histopathologically, mycosis fungoides is characterized mycosis cells [10]. The objective of this report is to appreciate the clinical course, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of epitheliotropic cutaneous lymphoma in a dog which has rarely been reported in Korea.

Case history and clinical findings: A seven-year-old castrated male Yorkshire terrier dog had a 6 year history of recurrent skin problems such as pruritus, excessive scales, and generalized erythema. Initial physical examination revealed an excess of scales, mild generalized erythema, and no palpable superficial lymph node. There was no evidence of skin infection in basic dermatologic examinations. Allergic dermatitis was suspected on the basis of these history and clinical signs. The dog was initially treated with oral prednisolone (0.25 mg/kg, BID), pentoxifylline (10 mg/kg, BID), and clemastine (0.05 mg/kg, BID). However, the dog did not show clinical improvement. Examination one month later showed a generalized distribution of raised plaques with overlying scales (Fig. 1), ulceration, depigmentation, erythema and tissue proliferation in the oral mucosal membrane, periocular area with exudates and crusts (Fig. 2).

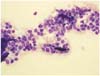

Clinical pathology: Smears of the oral mucous membranes and skin plaques aspirates were stained with aqueous Wright stain (Diff-Quik; International Reagents, Japan). The smears were moderately cellular and the dominant population consisted of medium sized lymphocytes with some macrophages. The lymphocytes had mild to moderate amounts of pale to weakly basophilic cytoplasms with eccentric nuclei or plasmacytic differentiation. Nuclei had fine and smooth chromatin and contained no visible nucleoli. (Fig. 3). These findings strongly suggested cutaneous lymphoma. Other differential diagnoses included histiocytoma, chronic inflammation, and plamsmacytomas.

A complete blood count, serum chemistry panel, and analysis of urine collected by cystocentesis were carried out. Hyepercalcemia (15.6 mg/dl) and increased alkaline phosphatase (417 U/l) were revealed in serum chemistry. Other abnormalities were not presented. Serum parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) and parathyroid hormone (PTH) concentration could not be measured.

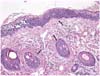

Biopsies were taken from the plaque of abdomen and trunk, fixed with 10% phospate-buffered formalin, routinely processed, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for light microscopic examination. Histologically, diffuse infiltrations of neoplastic lymphoid cells were noted in the intraepidermis and associated follicular epithelium (Fig. 4). The neoplastic cells were round and had distinct cell borders, hyperchromatic nuclei, and moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm were surrounded by clear space. The mitotic rate was low, averaging 1~2/hpf. Sparse to mild infiltration of neoplastic cells were also noted in the superficial dermis. Immunohistochemical studies were performed on paraffinembedded sections with antibodies to specific T-cell maker CD3, the B-cell and plasma cell maker CD79a, E-cadherin, and pancytokeratin using routine avidin-biotin complex methods [3]. The intraepithelial neoplastic cells were strongly positive for CD3 but were negative for CD79a, E-cadherin, and pancytokeratin, thus demonstrating that this tumor was of the T-lymphoid lineage in origin (Fig. 5).

Immunohistochemistry was performed to detect PTHrP (rabbit polyclonal, 1 : 100; Oncogene, USA) by the avidinbiotin-peroxidase complex method for neoplastic tissue, while normal skin was a positive control. However, neoplastic cells were negative for PTHrP.

Treatment: The dog was started on prednisolone (2 mg/kg, PO, BID) and isotretinoin (3 mg/kg/day, PO) [4,12]. After two weeks of therapy, the skin lesions were markedly improved. The serum calcium level was declined to 9.2 mg/dl. However the dog died unexpectedely. Permission for necropsy was denied by the owner.

Four stages have been used to describe the clinical appearance and course of mycosis fungoides: 1.generalized pruritic erythema and scaling (exfoliative erythroderma); 2. mucocutaneous erythema, infiltration, depigmentation, and ulceration; 3. solitary or multiple cutaneous plaque or nodules; 4. infiltrative and ulcerative oral mucosal disease [10]. The exofoliative erythroderma stage is usually misdiagnosed as allergy, scabies, or seborrhea [7]. In stage 3 to 4, clinical features of the disease is usually misdiagnosed as an immune-mediated skin disease (pemphigus vulgaris, bullous pemphigoid, or lupus erythematosus) or non neoplastic, chronic stomatitis. Initially, this patient, whose clinical signs were not controlled by glucocorticoid therapy, was also misdiagnosed with atopic dermatitis. As the disease progressed, a generalized distribution of slightly raised serpiginous or annular plaques with scales, mucocutaneous ulceration, erythema with exudates and crusts developed and the patient was finally diagnosed epitheliotropic T-cell cutaneous lymphoma. Mycosis fungoides may be similar to clinical signs or lesions of so many others diseases like atopic dermatitis, scabies, and pemphigus; therefore, clinicians should consider mycosis fungoides as a differential diagnosis. Although it is probably unnecessary to include mycosis fungoides in the differential diagnosis of the classic forms of these diseases, it should be suspected in patients that fail to respond to appropriate therapy for a more common condition [2,7].

Hypercalcemia is one of the most common paraneoplastic syndromes in dogs with lymphoma, occurring in approximately 10% to 40% of the clinical cases [8]. In dogs with lymphoma, 20% have elevated PTH-rP concentration [8] but hypercalcemia is not a common feature of mycosis fungoides [2]. In humans, Obagi et al. [9] reported that patients with mycosis fungoides who had hypercalcemia exhibited strong expression of PTH-rp in keratinocytes and abnormal lymphocytes while there was a slight immunoreactivity for PTH-rp in keratinocytes as well as the infiltrating lymphocytes in the skin from the patient with mycosis fungoides without hypercalcemia.

In this case, hypercalcemia was presented. However, plasma PTH-rP and PTH were not assayed. We performed immunhistochemistry for neoplastic tissues using anti-PTHrP antibody to detect PTH-rp. In immunohistochemistry, no immunoreactivity for PTHrP was shown in the epitheliotropic lymphoma tissue. Normal skin as a positive control was weakly positive for PTH-rP. Therefore, we could not conclude the reason for hypercalcemia with the mycosis fungoides in this case. Further investigations of hypercalcemia associated with canine mycosis fungoides are needed.

Therapy for mycosis fungoides in dogs has usually been of little or no benefit. Rarely, solitary nodules can be surgically excised, with long-term remissions or cures ensuing [10]. However recurrence is common.

The patient was treated with prednisolone and isotretinoin. Marked remission of clinical signs was obtained three weeks after the treatment. The patient died suddenly at night while visiting our hospital. Thus, we hypothesize that this treatment does not prevent extracutaneous development of neoplastic lesions or eventual death.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Hyperemia, tissue proliferation, erosion, and ulcer in the oral mucosal membrane with crusts and exudates.

References

1. Brown NO, Nesbitt GH, Patnaik AK, Gregory MacEwen E. Cutaneous lymphosarcoma in the dog: A disease with variable clinical and histologic manifestations. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1980. 16:343–345.

2. Campbell KL. . Small Animal Dermatology Secrets. 2004. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus;435–440.

3. Choi US, Jeong SM, Kang MS, Jung IS, Kim DY, Lee CW. Cutaneous lymphoma in a juvenile dog. Vet Clin Pathol. 2004. 33:47–49.

4. Donaldson D, Day MJ. Epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides) presenting as blepharoconjunctivitis in an Irish setter. J Small Anim Pract. 2000. 41:317–320.

5. Foster AP, Evans E, Kerlin RL, Vail DM. Cutaneous T-Cell lymphoma with Sezary syndrome in a dog. Vet Clin Pathol. 1997. 26:188–192.

6. Gregory MacEwen E, Withrow SJ. Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 2001. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;38–39. 558

7. McKeever PJ, Grindem CB, Stevens JB. Canine cutaneous lymphoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1982. 180:531–536.

8. Morrison WB. Cancer in Dogs and Cats. 2002. 2nd ed. Jackson: Teton Newmedia;643663–665.

9. Obagi S, DeRubertis F, BrownMPA-C L, Deng JS. Hypercalcemia and parathyroid hormone related protein expression in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Int J Dermatol. 1999. 38:855–862.

10. Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE. Muller & Kirk's Small Animal Dermatology. 2001. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Sanunders;1333–1338.

11. Thrall MA, Macy DW, Snyder SP, Hall RL. Cutaneous lymphosarcoma and leukemia in a dog resembling Sezary syndrome in man. Vet Pathol. 1984. 21:182–186.

12. White SD, Rosychuk RAW, Scott KV, Trettien AL, Jonas L, Denerolle P. Use of isotretinoin and etretinate for the treatment of benign cutaneous neoplasia and cutaneous lymphoma in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993. 202:387–391.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download