The 18q deletion syndrome occurs in approximately 1/40,000 live births, with a highly variable phenotype [1]. Cardiac anomaly is one of the common clinical features of this syndrome [2]. Although the size of the deletion and break points are variable, it does not correlate with the severity of clinical findings [3]. In this report, we describe a female newborn with a de novo 18q22. 1q23 deletion confirmed by microarray analysis, and a large atrial septal defect (ASD) causing cyanosis.

The patient was born at 44 weeks of gestation, by normal vaginal delivery of a 31-yr-old mother, and had a birth weight of 3,350 g (45-50th percentile). This girl was the second child of non-consanguineous, healthy parents. The patient was intubated and ventilated with 100% oxygen owing to severe initial cyanosis and respiratory distress after 2 hr of birth. Arterial blood gas analysis showed pH 7.367, PCO2 41.4 mmHg, PaO2 42 mmHg, base excess-2 mmol/L, HCO3 23.8 mmol/L, and 80% oxygen saturation, with a fractional inspired oxygen concentration of 1.0.

The chest radiograph showed a moderate sunburst sign without hyaline membrane disease or pneumothorax. Although the persistent cyanosis was sufficient to indicate pulmonary hypertension, an echocardiogram excluded it. Echocardiography revealed situs solitus with normal connections between the atria and the ventricles or the great arteries. The tricuspid valve and mitral valve motion were normal without any abnormality. However, there was a huge 16 mm ASD, almost the size of a single atrium, sufficient to cause cyanosis. Patent ductus arteriosus was observed with a left-to-right shunt, which closed spontaneously in a follow-up study.

A hyperoxia test also excluded lung abnormalities. Oxygen supply was then stopped, and the baby was weaned from mechanical ventilation. Suspecting congenital anomalies, a physical examination was performed by two pediatric physicians at the time of admission. No specific abnormalities were revealed, except for a short palpebral fissure, deep set eyes, and mild midfacial hypoplasia, which became evident at a 6-month follow-up. No hearing loss was observed on either side of the brain stem. Thyroid function test results were unremarkable (thyroid stimulating hormone: 1.55 µIU/mL, free thyroxine: 1.55 ng/dL).

At 6 months of age, the patient's growth was within normal range (weight, 7.1 kg, 25-50th percentile; height, 68.3 cm, 75th percentile) [4]. However, delayed developmental milestones were observed. She could not hold up her head above plane of body on ventral suspension and could not reach out both arms toward objects, which should appear by the age of 3 months [5].

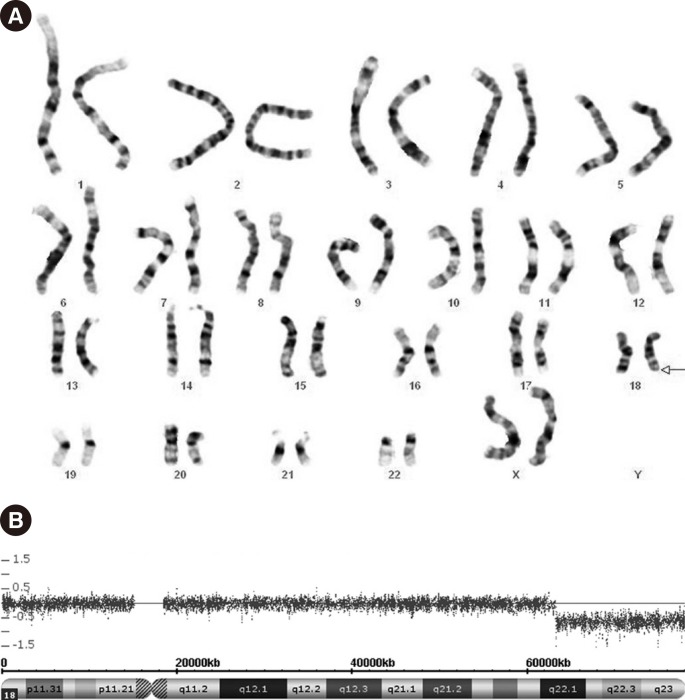

G-banded karyotype analysis (550-band level) performed on peripheral blood samples from the patient revealed the karyotype 46,XX,del(18)(q22.1) (Fig. 1A). Both parents showed normal karyotypes. Genomic DNA from the patient was analyzed by using the CytoScan750K Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic coordinates were based on the human reference sequence assembly (NCBI build 37[Hg19], February 2009). Array analysis on the patient's genomic DNA revealed a 15-Mb (63,244,135-78,013,728) deletion in 18q22.1q23 (Fig. 1B). Important OMIM genes identified as RTTN, CYB5A, TSHZ1, NFATC1, and CTDP1 were deleted.

RTTN encodes rotatin in humans, and mutations of RTTN are known to cause polymicrogyria [6]. However, the effect of complete RTTN loss on human cardiac anomaly has not been studied thus far.

CYB5A encodes a membrane-bound cytochrome, and the loss of this gene can cause hereditary methemoglobinemia, which can further lead to cyanosis. However, methemoglobinemia was not reported in the 18q deletion syndrome, which usually involves CYB5A gene loss. Moreover, our patient showed only 0.8% of methemoglobin in arterial blood detected by a RAPID lab 1265 blood gas analyzer (Siemens Diagnostics, Medfield, MA, USA) at 90 days after birth.

TSHZ1 deletion or mutation can cause congenital aural atresia in the 18q deletion syndrome [7]. A previously reported critical region on chromosome 18 for congenital aural atresia is 18q22.3-18q23 [8]. Although the 18q22.1q23 deletion reported herein encompasses the critical region for congenital aural atresia, including TSHZ1 loss, our patient did not show any auditory anomalies.

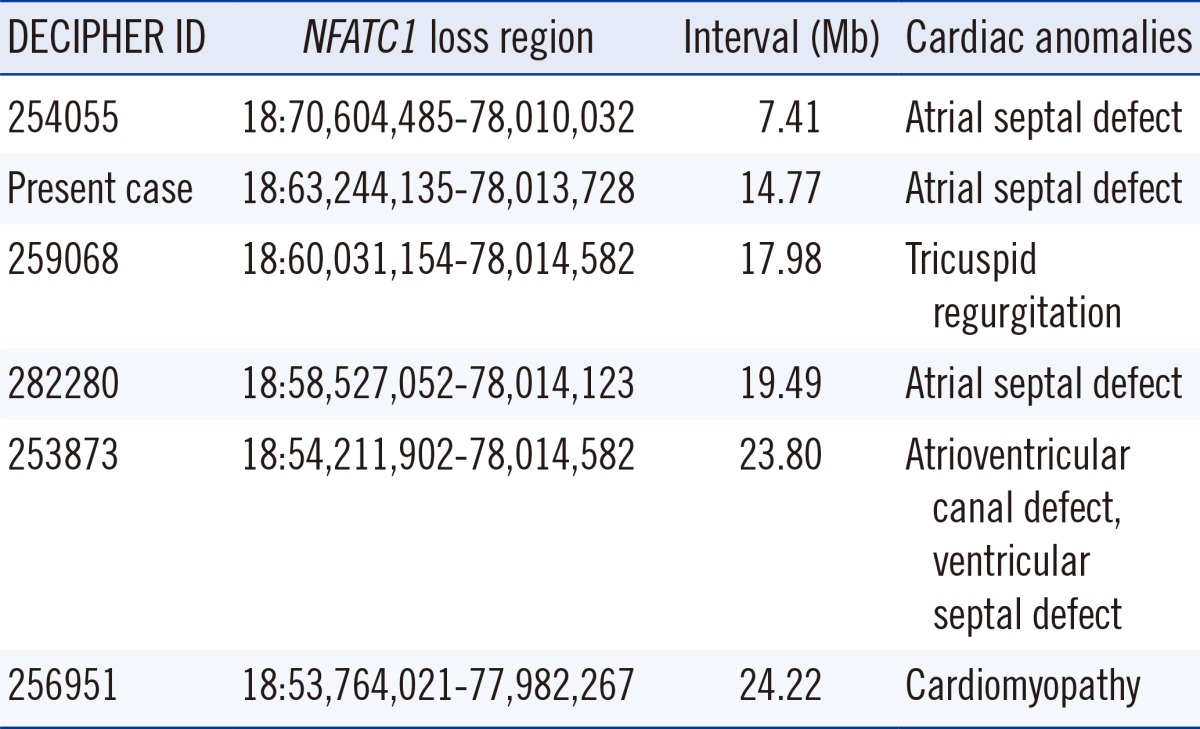

NFATC1 has been known to have a role in human cardiac development, and an insufficiency of the NFATC1 gene product could lead to Ebstein's anomaly [9]. In the DECIPHER database, cardiac anomalies associated with the loss of NFATC1 included atrioventricular canal defect, ventricular septal defect, cardiomyopathy, tricuspid regurgitation, and atrial septal defect; the breakpoints ranged from 53.7 to 70.6 Mb (Table 1) [10]. On the basis of all the cardiac abnormalities found in this chromosomal region in DECIPHER, combined with the breakpoint position (63.2 Mb) and loss of NFATC1 in the patient, multiple cardiac abnormalities were suspected; however, only a single, huge ASD was detected by echocardiography.

While the CTDP1 mutation is a probable cause of congenital cataracts, facial dysmorphism, and neuropathy syndrome (OMIM 604168), the present case of loss of CTDP1 did not show other related symptoms, except for mild facial dysmorphism at a 6-month follow-up.

Except for the large ASD, which rarely causes cyanosis, the phenotype of our case was relatively mild compared with other cases of 18q deletion syndrome having similar deletion sizes. Other factors could be correlated with the loss of genes on the 18q terminal region in order to explain various phenotypes, regardless of the size of the deletion in 18q. Our case supports a relationship between the 18q terminal deletion and ASD, which could be useful for further studies on genotype-phenotype correlations between the18q deletion syndrome and cardiac anomaly.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient and her parents for their dedicated participation. This study made use of data generated by the DECIPHER Consortium. A full list of centers that contributed to the generation of the data is available from https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk and via email from decipher@sanger.ac.uk.

References

1. Cody JD, Ghidoni PD, DuPont BR, Hale DE, Hilsenbeck SG, Stratton RF, et al. Congenital anomalies and anthropometry of 42 individuals with deletions of chromosome 18q. Am J Med Genet. 1999; 85:455–462. PMID: 10405442.

2. Feenstra I, Vissers LE, Orsel M, van Kessel AG, Brunner HG, Veltman JA, et al. Genotype-phenotype mapping of chromosome 18q deletions by high-resolution array CGH: an update of the phenotypic map. Am J Med Genet A. 2007; 143A:1858–1867. PMID: 17632778.

3. Miller G, Mowrey PN, Hopper KD, Frankel CA, Ladda RL. Neurologic manifestations in 18q- syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1990; 37:128–132. PMID: 1700607.

4. Moon JS, Lee SY, Nam CM, Choi JM, Choe BK, Seo JW, et al. 2007 Korean national growth charts: review of developmental process and an outlook. Korean J Pediatr. 2008; 51:1–25.

5. Heo KH, Squires J. KASQ: Korean Ages and Stages Questionnaires/parent-completed development screening tool. Seoul: Seoul community rehabilitation center;2006.

6. Kheradmand Kia S, Verbeek E, Engelen E, Schot R, Poot RA, de Coo IF, et al. RTTN mutations link primary cilia function to organization of the human cerebral cortex. Am J Hum Genet. 2012; 91:533–540. PMID: 22939636.

7. Feenstra I, Vissers LE, Pennings RJ, Nillessen W, Pfundt R, Kunst HP, et al. Disruption of teashirt zinc finger homeobox 1 is associated with congenital aural atresia in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2011; 89:813–819. PMID: 22152683.

8. Veltman JA, Jonkers Y, Nuijten I, Janssen I, van der Vliet W, Huys E, et al. Definition of a critical region on chromosome 18 for congenital aural atresia by array CGH. Am J Hum Genet. 2003; 72:1578–1584. PMID: 12740760.

9. van Trier DC, Feenstra I, Bot P, de Leeuw N, Draaisma JM. Cardiac anomalies in individuals with the 18q deletion syndrome; report of a child with Ebstein anomaly and review of the literature. Eur J Med Genet. 2013; 56:426–431. PMID: 23707655.

10. Corpas M BE, Clayton S, Bevan P, Firth HV. DECIPHER: Database of Chromosomal Imbalance and Phenotype in Humans using Ensembl Resources. Updated on Jul 2014. https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download