Abstract

Carcinosarcoma of gallbladder (CSGB) is a rare malignancy characterized by malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components. Its pathogenesis is unknown and most CSGBs are associated with poor survival because the disease normally presents at an advanced stage, and as a result, curative resection is uncommon. This report describes a case that underwent curative resection. A 77-year-old woman presented with right upper quadrant pain. The preoperative diagnosis was gallbladder (GB) cancer, and thus, curative radical cholecystectomy was performed. However, pathologic examination of the surgical specimen revealed that the tumor was composed of two histologic components of squamous cell carcinoma and spindle cell sarcoma, which was consistent with a diagnosis of carcinosarcoma. The tumor was found to extend to the perimuscular connective tissue and to have metastasized to one lymph node (LN). The prognosis of CSGB remains poor despite curative resection, and thus, the authors recommend that effort be made to improve surgical outcomes.

The vast majority of gallbladder (GB) cancers are adenocarcinomas with carcinosarcomas accounting for fewer than 1% of GB cancers. Carcinosarcoma is characterized by malignant epithelial and mesenchymal elements, and has been reported in many different organs, including the uterus, lung, esophagus, kidney, and pancreas [1]. The prognosis of patients with carcinosarcoma of the gallbladder (CSGB) has been reported to be poor [2]. Accordingly, in most cases curative resection is not possible. The invasive nature and aggressive biology of CSGB adequately explains the limited number of resectabxle cases. Here, we report a case of CSGB treated by curative radical cholecystectomy.

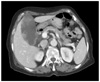

A 77-year-old woman was admitted via our emergency department due to a complaint of severe right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain of one day's duration. Her medical history revealed that she was undergoing treatment for unstable angina. A physical examination revealed a woman in acute distress. Her blood pressure was 150/70 mmHg yet other vital signs were stable. She had no abnormal finding on chest examination. She had mild tenderness in the RUQ, but no rebound tenderness or muscle guarding. She was negative for Murphy's sign. Laboratory findings showed a white blood cell count of 17,000/mm3 (seg; 88%), hemoglobin 10.0 g/dL, C-reactive protein 6.418 mg/dL, serum albumin 2.9 g/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 253 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase 58 U/L. Other laboratory test results, including electrolyte and urinalysis findings, were within normal limits. A tumor marker examination revealed that alpha-fetoprotein (αFP) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were within the normal range, but that carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and cancer antigen 125 (CA125) were mildly elevated (CA19-9 42.6 U/mL and CA125 42.1 U/mL). Chest and abdominal radiographs, electrocardiography, and echocardiography failed to depict any significant abnormality. However, abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed diffuse GB distension and an irregular intraluminal polypoid mass with no demonstrable lymph nodes (LNs) in the pericholecystic and upper abdominal regions (Fig. 1). These radiologic findings suggested GB cancer and, thus, we diagnosed GB cancer and scheduled surgery. At laparotomy, the GB was found to be enlarged to about 6 × 10 cm and to have a thick wall. There was no evidence of distant metastasis. The patient underwent cholecystectomy, which included resection of 3 to 5 cm wedge of liver tissue at the gallbladder bed, and combined LN dissection. Frozen section examination indicated that all resection margins were cancer cell free.

The postoperative specimen showed a tumor size of 7.8 × 5.5 × 1.2 cm, and histologically, the tumor was found to contain distinct regions of squamous cell carcinoma and high-grade spindle cell sarcoma (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the tumor was found to have extended to perimuscular connective tissue and to have metastasized to one of the 14 LNs excised. The stage of patient was classified as type IIIB (T2N1M0) using the classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Final diagnosis was made based on immunohistochemical findings, that is, squamous carcinoma components were stained by cytokeratin but not by vimentin, and conversely, sarcoma components were stained by vimentin but not by cytokeratin (Fig. 3).

Her postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged 14 days postoperatively. The patient and her family refused postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. At 1 month postoperative, abdominal CT revealed no cancer recurrence, but at 70 days postoperative, she revisited our hospital complaining of nausea, vomiting, indigestion, melena, and general weakness. Abdominal CT performed at the time showed a huge metastatic mass involving S4 of the liver, the 1st portion of the duodenum, and multiple, variably sized, cancerous masses with central necrosis in the dependant portion of the abdominal cavity (Fig. 4). Conservative treatment was initiated but she died a few days later.

GB cancers account for 1 to 2% of all cancers. Adenocarcinoma accounts for the majority of primary malignant neoplasms of the GB, and squamous cell carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, tumors with choriocarcinoma-like differentiation, and sarcoma account for the remainder [1]. CSGBs are rare and constitute less than 1% of GB cancers. The symptoms of CSGB are non-specific. The preoperative diagnosis of CSGB is difficult because imaging studies, such as, ultrasonography, CT, and abdominal angiography cannot differentiate it from carcinoma of the GB. Tumor markers such as αFP, CEA, CA19-9 and CA125 are also non-specific [2,3]. Carcinosarcomas are characterized by malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components. The most common epithelial component is adenocarcinoma, but a squamous cell carcinoma component is also frequently present. Furthermore, squamous cell carcinoma is known to grow at twice the speed of adenocarcinomas and to have a poorer prognosis [4]. The most frequent mesenchymal component is spindle cell sarcoma, followed by bone, cartilage, and other mesenchymal tissues [2]. Due to their rarity, the histogenesis and natural history of carcinosarcoma is uncertain. They are generally classified into two groups, namely, "true carcinosarcomas" and "so-called carcinosarcomas. True carcinosarcomas, in which a carcinoma and sarcoma arise simultaneously, exhibit apparent sarcomatous differentiation toward specific tissues, such as, osteoid, cartilage, or striated muscle, whereas so-called carcinosarcomas, in which a sarcomatous reaction occurs in a carcinoma, exhibit epithelial differentiation in a sarcomatoid component, and are termed sarcomatoid or spindle cell carcinomas [5]. The diagnosis of CSGB must be confirmed by microscopic findings and immunohistochemical staining. Microscopically, the diagnosis of CSGB requires the presence of both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal elements, though these may be intimately admixed and show characteristics intermediate between the two cell types. By immunohistochemistry, the carcinomatous component is positive for epithelial markers, such as, cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and the sarcomatoid component is positive for mesenchymal markers like vimentin, desmin and actin.

In CSGB, the sarcomatoid component is negative for epithelial markers, such as, cytokeratin, EMA, whereas sarcomatoid carcinoma is positive for epithelial markers, such as, cytokeratin and EMA [5,6]. In our case, the tumor was composed of squamous cell carcinoma and spindle cell sarcoma, and the squamous cell carcinoma component was positive for cytokeratin and negative for vimentin, whereas the spindle cell sarcoma component was negative for cytokeratin and positive for vimentin.

Therapeutic interventions have not been well defined and no optimal postoperative adjuvant therapy, such as, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, has been established because of the rarity of CSGB and its poor prognosis. CSGB is treated in the same way as other gallbladder cancers. Accordingly, the best treatment option is surgical excision. Cholecystectomy alone is sufficient for cancer cells confined to the lamina propria, whereas more advanced states require resection of a 3 to 5 cm wedge of liver tissue at the gallbladder bed, combined with LN dissection in the absence of evidence of distant metastasis. More extensive procedures, such as, right hepatectomy, probably increase risk and confer no survival benefit [2-5]. In our case, there was no evidence of distant metastasis or of invasion of adjacent organs, and we performed curative radical cholecystectomy.

The prognosis of CSGB patients has been reported to be poor. In many patients at presentation, tumors are large and nodular and invade peripheral organs. Mean survival after diagnosis is only a few months in such cases. The overall 5-year survival rate after surgery is 31.0%. [3] Two factors importantly predict a good prognosis; curative resection and early stage (stage I or stage II) disease, according to the AJCC classification. The 5-year survival rate after curative resection for CSGB is 88.9% when invasion is restricted to the muscularis propria [2,4,6,7]. CSGB may recur as liver metastasis, peritoneal dissemination, or as LN metastasis.

The majority of recurrences occur within half a year of surgery and for those that succumb to the disease, median time to recurrence is 50 days. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy options for CSGB are not well defined. Previous studies have reported the use of chemoradiotherapy after surgical resection, but this treatment conferred no clear advantage [8,9]. In our patient, despite curative resection, the prognosis was expected to be poor due to the presence of the squamous cell carcinoma component and a IIIB postoperative pathologic stage.

CSGB is a rare tumor, characterized by both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components with a poorer prognosis than ordinary gallbladder adenocarcinoma. If curative resection is performed in stage I or II, a good prognosis is possible. More clinicopathological data and further studies are required to identify the prognostic indicators and the histogenesis of gallbladder carcinosarcoma.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Abdomen computed tomography showed diffuse distension of gallbladder (GB) with irregular intraluminal polypoid masses - possible GB cancer rather than xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis.

Fig. 2

Microscopic finding. (A) Well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma components (H&E, ×200). (B) High-grade spindle cell sarcoma components (H&E, ×400).

References

1. Baillie J. Tumors of the gallbladder and bile ducts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999. 29:14–21.

2. Huguet KL, Hughes CB, Hewitt WR. Gallbladder carcinosarcoma: a case report and literature review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005. 9:818–821.

3. Okabayashi T, Sun ZL, Montgomey RA, Hanazaki K. Surgical outcome of carcinosarcoma of the gall bladder: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2009. 15:4877–4882.

4. Uzun MA, Koksal N, Gunerhan Y, Celik A, Guneş P. Carcinosarcoma of the gallbladder: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009. 39:168–171.

5. Nishihara K, Tsuneyoshi M. Undifferentiated spindle cell carcinoma of the gallbladder: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and flow cytometric study of 11 cases. Hum Pathol. 1993. 24:1298–1305.

6. Guo KJ, Yamaguchi K, Enjoji M. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the gallbladder. A clinicopathologic, histochemical, and immunohistochemical study of 21 patients with a poor prognosis. Cancer. 1988. 61:1872–1879.

7. Liu KH, Yeh TS, Hwang TL, Jan YY, Chen MF. Surgical management of gallbladder sarcomatoid carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009. 15:1876–1879.

8. Lumsden AB, Mitchell WE, Vohman MD. Carcinosarcoma of the gallbladder: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 1988. 54:492–494.

9. Hotta T, Tanimura H, Yokoyama S, Ura K, Yamaue H. So-called carcinosarcoma of the gallbladder; spindle cell carcinoma of the gallbladder: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002. 32:462–467.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download