Uterine carcinosarcoma/malignant mixed Müllerian tumor (UC/MMMT) is an uncommon and aggressive gynecological malignancy with poor prognosis. Tumors arise from monoclonal carcinoma cells derived from embryonal mesoderm, which exhibit sarcomatous metaplasia. UC/MMMT usually occurs in postmenopausal women and accounts for 2%-5% of all uterine malignancies [12]. The five-year survival rates are particularly poor (21%-39%). Several case reports and case series describe UC/MMMT occurring after tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer [3456789]. Retrospective studies suggest that the increased incidence of these high-risk malignancies is greater than the observed increase in incidence of endometrial tumors generally following tamoxifen therapy [10111213], though the number of subjects with UC/MMMT in any of these studies is small. The increase in uterine cancers generally following tamoxifen therapy is thought to be driven by the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) through a positive trophic effect on the uterine corpus. Although tamoxifen binds ERβ with equal affinity, there is no observed activation of this receptor [1415]. Whether ER activation exerts any positive effect on UC/MMMTs remains equivocal. Other studies suggest that tamoxifen may upregulate expression of the HER2/neu oncogene in UC/MMMT cells [1617], although any potential effect on the behavior of these malignancies is far from clear. As tamoxifen metabolites can covalently bind DNA, principally forming (E)- and (Z)-α-(deoxyguanosin-N2-yl)-4-hydroxytamoxifen adducts [18], the possibility that tamoxifen therapy is inherently carcinogenic has also been considered. However, tamoxifen-DNA adduct formation in uterine tissues following oral administration occurs at levels too low to be consistent with this being the mechanism driving such endometrial cancers [19].

We identified two unrelated women who developed UC/MMMT as a second primary malignancy following BRCA1-associated breast cancer. Neither of these women received hormone therapy, as their tumors were histologically determined to be unresponsive to hormone therapy (i.e., ER-/progesterone receptor [PR]-). Patient 1 had BRCA1 c.5503C>T (p.Arg1835*), developed breast cancer at 36 years, which was managed with lumpectomy and local radiotherapy, and subsequently developed UC/MMMT at 48 years. Patient 2 had BRCA1 c.2560_2561dupGC (p.Gln855fs), developed breast cancer at 34 years, again treated with lumpectomy and local radiotherapy, and was found to have UC/MMMT at 56 years. Although BRCA1 mutation carriers are at increased risk of developing endometrial cancers compared to the general population, most of this risk is attributable to tamoxifen use [20]. It has also been suggested that BRCA1 mutations may predispose carriers to uterine papillary serous carcinoma specifically [2122]. However, UC/MMMT is not recognized as part of the BRCA1 phenotype. Prompted by this unexpected finding, we conducted a retrospective population-based study to establish whether an association exists between breast cancer and UC/MMMT generally and whether a breast tumor being ER-/PR- has any bearing on this.

We reviewed data from all 387 patients in the Northern and Yorkshire Cancer Registry who were diagnosed with UC/MMMT between January 1998 and December 2007. We also analyzed data for all 85,930 women who could have potentially developed UC/MMMT following breast cancer during this period, i.e., any woman alive for any part of the study period who had been diagnosed with breast cancer at any time prior to the study end date. Data included age at cancer diagnoses and whether hormone therapy had been given at any time for this, as a proxy for ER/PR status of the breast cancer. All study information was released to us in fully anonymized form. As cancer registration is a statutory requirement in the UK, we expect our dataset to be fully representative of the registry population, although we cannot exclude the possibility of minor omissions in the recording of therapies that were started after the registered treatment period.

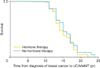

Three hundred eighty-seven patients were diagnosed with UC/MMMT between January 1998 and December 2007, accounting for 5.7% of all recorded uterine malignancies. The mean age at diagnosis was 71 years (range, 28 to 101 years). 85,930 women were alive for at least part of the study period having been diagnosed with breast cancer. In 87 of UC/MMMT cases (22.5%), UC/MMMT represented a second primary malignancy following breast cancer, with an interval of 10-20 years. In a further six UC/MMMT patients (1.6%), UC/MMMT preceded a diagnosis of breast cancer. This co-occurrence of breast cancer together with UC/MMMT in 24% of UC/MMMT patients is significantly higher (p<0.001) than the breast cancer rate (3.0%) seen, at the midpoint of the study period, in women >20 years of age without UC/MMMT. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used with a Cox proportional hazards regression to test the effect of hormone therapy on time to UC/MMMT following breast cancer, against the hypothesis that there would be no difference between the groups. Hormone therapy, as a proxy for hormone receptor status, has no significant effect on the development of UC/MMMT following breast cancer (p=0.55) (Fig. 1). However, the number of cases of UC/MMMT occurring in women following an independent diagnosis of breast cancer (87 out of 85,930) is higher than expected (p<0.001).

This study comprises the largest cohort of UC/MMMT patients to date and suggests that receipt of hormone therapy for breast cancer has negligible effect on the incidence of these tumors. However, the observation that UC/MMMT is overrepresented in our breast cancer population suggests that there may be an as yet unknown, possibly genetic, component to the development of such malignancies. Another potential explanation is that systemic treatment for a primary cancer, i.e., chemotherapy, may increase the likelihood of a second malignancy among treated individuals; however, our patients were managed with surgery and local radiotherapy only. Having identified unrelated women diagnosed with UC/MMMT following ER-/PR-, BRCA1-associated breast cancers, it may be that these aggressive gynecological tumors are a rare manifestation of this high risk genetic cancer predisposition syndrome, which may be avoided by prophylactic hysterectomy. While the risk-reducing role of prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in promoting long-term survival among BRCA1/2 carriers is already established [23], a similar approach may not be clinically practicable for malignancies as rare as UC/MMMT. Further genetic studies of the UC/MMMT population are required to properly establish whether BRCA1/2-or other genes-make a substantial contribution to this clinical phenotype. If so, newer, targeted therapies, such as the PARP inhibitors [24], may be considered as potential candidates to reduce mortality associated with UC/MMMT.

Figures and Tables

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Ruth Burns and Clive D. Griffiths, of the Northern and Yorkshire Cancer Registry and Information Service (NYCRIS), who provided advice and registry data for this work.

References

1. Kernochan LE, Garcia RL. Carcinosarcomas (malignant mixed Müllerian tumor) of the uterus: advances in elucidation of biologic and clinical characteristics. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009; 7:550–556.

2. Ho SP, Ho TH. Malignant mixed Mullerian tumours of the uterus: a ten-year experience. Singapore Med J. 2002; 43:452–456.

3. Friedrich M, Villena-Heinsen C, Mink D, Bonkhoff H, Schmidt W. Carcinosarcoma, endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma and endometriosis after tamoxifen therapy in breast cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999; 82:85–87.

4. Fotiou S, Hatjieleftheriou G, Kyrousis G, Kokka F, Apostolikas N. Long-term tamoxifen treatment: a possible aetiological factor in the development of uterine carcinosarcoma: two case-reports and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2000; 20:2015–2020.

5. McCluggage WG, Abdulkader M, Price JH, Kelehan P, Hamilton S, Beattie J, et al. Uterine carcinosarcomas in patients receiving tamoxifen: a report of 19 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2000; 10:280–284.

6. Kloos I, Delaloge S, Pautier P, Di Palma M, Goupil A, Duvillard P, et al. Tamoxifen-related uterine carcinosarcomas occur under/after prolonged treatment: report of five cases and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002; 12:496–500.

7. Hubalek M, Ramoni A, Mueller-Holzner E, Marth C. Malignant mixed mesodermal tumor after tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004; 95:264–266.

8. Yildirim Y, Inal MM, Sanci M, Yildirim YK, Mit T, Polat M, et al. Development of uterine sarcoma after tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer: report of four cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005; 15:1239–1242.

9. Arenas M, Rovirosa A, Hernandez V, Ordi J, Jorcano S, Mellado B, et al. Uterine sarcomas in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006; 16:861–865.

10. Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Sherman ME, Fraumeni JF Jr. Risk of malignant mixed mullerian tumors after tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004; 96:70–74.

11. Rieck GC, Freites ON, Williams S. Is tamoxifen associated with high-risk endometrial carcinomas? A retrospective case series of 196 women with endometrial cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005; 25:39–41.

12. Swerdlow AJ, Jones ME. British Tamoxifen Second Cancer Study Group. Tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and risk of endometrial cancer: a case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005; 97:375–384.

13. Saadat M, Truong PT, Kader HA, Speers CH, Berthelet E, McMurtrie E, et al. Outcomes in patients with primary breast cancer and a subsequent diagnosis of endometrial cancer: comparison of cohorts treated with and without tamoxifen. Cancer. 2007; 110:31–37.

14. Watanabe T, Inoue S, Ogawa S, Ishii Y, Hiroi H, Ikeda K, et al. Agonistic effect of tamoxifen is dependent on cell type, ERE-promoter context, and estrogen receptor subtype: functional difference between estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997; 236:140–145.

15. Zafrakas M, Kostopoulou E, Dragoumis K, Mikos T, Papadimas J, Bontis J. Expression of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in two uterine mesenchymal tumors after prolonged tamoxifen therapy: report of two cases. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2004; 25:530–533.

16. Raspollini MR, Mecacci F, Paglierani M, Marchionni M, Taddei GL. HER-2/neu oncogene in uterine carcinosarcoma on tamoxifen therapy. Pathol Res Pract. 2005; 201:141–144.

17. Amant F, Vloeberghs V, Woestenborghs H, Debiec-Rychter M, Verbist L, Moerman P, et al. ERBB-2 gene overexpression and amplification in uterine sarcomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2004; 95:583–587.

18. Marques MM, Beland FA. Identification of tamoxifen-DNA adducts formed by 4-hydroxytamoxifen quinone methide. Carcinogenesis. 1997; 18:1949–1954.

19. Martin EA, Brown K, Gaskell M, Al-Azzawi F, Garner RC, Boocock DJ, et al. Tamoxifen DNA damage detected in human endometrium using accelerator mass spectrometry. Cancer Res. 2003; 63:8461–8465.

20. Segev Y, Iqbal J, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Lynch HT, Moller P, et al. The incidence of endometrial cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: an international prospective cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013; 130:127–131.

21. Pennington KP, Walsh T, Lee M, Pennil C, Novetsky AP, Agnew KJ, et al. BRCA1, TP53, and CHEK2 germline mutations in uterine serous carcinoma. Cancer. 2013; 119:332–338.

22. Hecht JL, Konstantinopoulos PA, Awtrey CS, Soslow RA. Immunohistochemical loss of BRCA1 protein in uterine serous carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014; 33:282–287.

23. Evans DG, Ingham SL, Baildam A, Ross GL, Lalloo F, Buchan I, et al. Contralateral mastectomy improves survival in women with BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013; 140:135–142.

24. Drew Y, Mulligan EA, Vong WT, Thomas HD, Kahn S, Kyle S, et al. Therapeutic potential of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor AG014699 in human cancers with mutated or methylated BRCA1 or BRCA2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011; 103:334–346.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download