Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of nodal staging surgery before chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for locally advanced cervical cancer in the era of positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT).

Methods

A modified Markov model was constructed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of para-aortic staging surgery before definite CRT when no uptake is recorded in the para-aortic lymph nodes (PALN) on PET/CT. Survival and complication rates were estimated based on the published literature. Cost data were obtained from the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Strategies were compared using an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). Sensitivity analyses were performed, including estimates for the performance of PET/CT, postoperative complication rate, and varying survival rates according to the radiation field.

Results

We compared two strategies: strategy 1, pelvic CRT for all patients; and strategy 2, nodal staging surgery followed by extended-field CRT when PALN metastasis was found and pelvic CRT otherwise. The ICER for strategy 2 compared to strategy 1 was $19,505 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). Under deterministic sensitivity analyses, the model was relatively sensitive to survival reduction in patients who undergo pelvic CRT alone despite having occult PALN metastasis. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis demonstrated the robustness of the case results, with a 91% probability of cost-effectiveness at the willingness-to-pay thresholds of $60,000/QALY.

For patients with locally advanced cervical cancer (LACC), the current guidelines recommend primary chemoradiotherapy (CRT) [1]. Therefore, pre-therapeutic staging has an important role in the management of patients with LACC. Assessment of the nodal involvement of para-aortic lymph nodes (PALN) is critical to determine the field of radiation therapy (RT).

The value of pre-treatment surgical PALN assessment has been evaluated in previous studies; however, the survival benefit of surgical staging has not yet been determined. One randomized trial failed to show any benefit of surgical staging [2]. This trial was stopped prematurely after an interim analysis owing to a significant reduction in survival for patients staged surgically. Conversely, surgical staging has been shown to improve survival compared to conventional radiological staging in three Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) trials (GOG 85, GOG 120, and GOG 165) [3]. Recently, a Cochrane review concluded that the decision to offer pre-treatment surgical PALN assessment needs to be individualized in LACC [4].

In the era of positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), the role of surgical staging should be re-evaluated. PET/CT is the most accurate imaging method for assessing extrapelvic disease in LACC [5]. Its high true-positive rate for PALN metastasis suggests that surgical staging is unnecessary when uptake is noted in the paraaortic area. However, the overall false-negative rate of PALN involvement is around 12%, most of which is attributable to non-detectable nodal disease [6]. As such, surgical staging is potentially beneficial for patients who test negative for PALN on PET/CT. Considering postoperative complications and the high cost of surgical staging, a comprehensive cost-effective analysis is required to clarify the best treatment strategy for patients with LACC [47].

We sought to create a model to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of nodal staging surgery followed by tailored CRT compared to pelvic CRT for the treatment of LACC when no uptake is found in PALN on PET/CT.

A modified Markov model was constructed using TreeAge Pro software (TreeAge Software Inc., Williamstown, MA, USA). The model evaluated two strategies for patients with stage IIB or higher disease that were scheduled to undergo CRT for curative intent when no uptake was recorded in PALN on PET/CT (Fig. 1). The strategies were (1) pelvic CRT in line with PET/CT results and (2) nodal staging surgery, followed by extended-field CRT if PALN metastasis was found and pelvic CRT otherwise. The Markov states were (1) active treatment; (2) completed primary treatment without complications; (3) completed primary treatment with acute complications; (4) completed primary treatment with late complications; and (5) death. The cycle length was 1 year, and the time horizon for the analysis was 5 years.

Under strategy 1, all patients were assumed to receive whole pelvic external-beam radiation (WPRT), six cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy, and additional vaginal cylinder brachytherapy regardless of PALN status. Under strategy 2, all patients were assumed to receive PALN dissection up to renal vessel level followed by definite CRT; if PALN metastasis was found following surgery, extended-field RT, six cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy, and additional brachytherapy would be performed; if no metastasis was found in the PALN, patients would undergo WPRT, six cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy, and brachytherapy. The baseline model was developed from a payer's perspective. Costs included hospital and professional costs associated with surgery, CRT, treatment of toxicity, and complications. Institutional Review Board approval was waived in this cost-effectiveness analysis due to using datasets open to the public.

Survival data were extracted from the literature. We categorized three cohorts to estimate outcomes: cohort 1, patients who undergo pelvic CRT without PALN metastasis; cohort 2, patients who undergo pelvic CRT only, despite the presence of occult PALN metastasis (unstaged PALN metastasis); and cohort 3, patients who undergo extended-field CRT due to PALN metastasis (fully staged PALN metastasis). Strategy 1 included the outcomes of cohorts 1 and 2, while strategy 2 included the outcomes of cohorts 1 and 3.

For patients receiving pelvic CRT in the setting of no PALN involvement, 5-year overall survival was estimated based on the published literature [891011]. Survival for individuals with occult PALN metastasis treated with extended-field CRT (cohort 3) was similar to that for patients without PALN metastasis and whose disease was managed with pelvic CRT alone (cohort 1) [1213]. As no survival data were available for patients who receive pelvic CRT only, despite the presence of PALN metastasis (cohort 2), this assumption was varied in the sensitivity analysis to correct for the uncertainty in the assumption. Five-year overall survival for patients with unstaged PALN metastasis (cohort 2) was modeled at 45%, reflecting a 30% reduction in survival compared to nodal staging surgery followed by extended-field CRT in occult PALN metastasis (cohort 3). Considering the 12% baseline false-negative rate for PET/CT in detecting PALN metastasis, strategy 1 included 88% of cohort 1 and 12% of cohort 2, and strategy 2 consisted of 88% of cohort 1 and 12% of cohort 3. Assuming that the survival rate in cohort 2 was 30% less than that in cohort 3, we could infer that the 5-year overall survival rate for patients in strategy 2 was approximately 2.4% higher than that of patients in strategy 1 in terms of baseline PET/CT performance.

Quality of life (QOL) adjustments are listed in Table 1. We also assumed same utility conditions as suggested in a previous study [14]. QOL during the treatment phase was estimated at 0.76 [15]. For the 3 months of recovery from radiotherapy (RT), utility was assumed to be 0.86 [16]. Loss in QOL from acute gastrointestinal (GI) complications was based on toxicity for grade 3 to 4 nausea/vomiting/anorexia and diarrhea or proctitis [1718]. Acute genitourinary (GU) QOL was estimated based on the utility value for cystitis [19]. Patient QOL from chronic GI and GU toxicities was based on utilities for bowel obstruction and rectovaginal/vesicovaginal fistula [20]. Upon completion of active treatment, patients were assumed to return to a cervical cancer survivor utility score for Korea (0.898) unless they experienced late complications, in which case the appropriate utility score was then applied [21].

We assumed the same toxicity conditions as suggested in a previous study [14]. In this study, toxicity was based on conventional RT technology. Baseline probability estimates are shown in Table 1. Acute GI toxicities include nausea/vomiting/anorexia and diarrhea or proctitis. Bowel obstruction was included as a chronic GI condition. Acute GU toxicities included cystitis, and chronic GU conditions were rectovaginal and vesicovaginal fistulas.

Costs were incorporated into the model using claims data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (Table 2). Amounts are expressed in US dollars; the exchange rate was 1,121.00 Korean won to one US dollar in July 2013. A payer perspective was used.

Costs excluding complications were investigated using microcosting, which calculates costs after listing the total resources used and matching the unit cost of each component. Nodal staging surgery costs included fees for laparoscopic surgery, pathology, anesthesia, and 4 days of admission. Since intensity-modulated RT was not commonly used in Korea at that time, its associated cost was not included in this model. Chemotherapy costs were calculated for a hypothetical woman with a body surface area of 1.5 m2 and included the cost of administration, pre-medication, and the chemotherapeutic agent. The calculated dose for the chemotherapy regimen was cisplatin at 40 mg/m2. For complications, patient-level costs were collected and the average cost calculated. All patients were assumed to incur the cost of cancer treatment, excluding palliative care, when entering the first Markov cycle. Costs attributed to the final year of life were obtained from a retrospective assessment of Korean health-care costs attributed to the last year of life in patients with terminal cervical cancer [22].

Key assumptions of our study are as follows: (1) all surgical staging is performed using an extraperitoneal laparoscopic approach, and nodal staging surgery is 100% sensitive and specific; (2) if PET/CT shows negative findings in PALN, occult nodal metastases (unstaged PALN) measure less than 5 mm at the time of surgical staging; and (3) definite CRT is performed within 4 weeks of nodal staging surgery and no damage results from a delay in starting curative treatment. In addition, we do not consider other postoperative complications, with the exception of lymphoceles and lymphedema, as the incidence of these complications is very low if a highly skilled surgeon performs the operation using an extraperitoneal approach.

Effectiveness was calculated in quality-adjusted life years (QALY). Costs are discounted at 5% annually. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is the ratio of the additional economic impact of a strategy relative to the improvement in QALY.

We conducted one-way sensitivity and probabilistic sensitivity analyses to evaluate the impact of a variation in parameters on the resulting ICER. One-way sensitivity analyses were carried out based on the performance of PET/CT (false-negative rates), rates of postoperative complications, and survival reduction when pelvic CRT alone was performed for patients with unstaged PALN metastasis. To quantify the comprehensive effect of uncertainty, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis was tested using a Monte Carlo simulation.

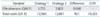

In the base-case analysis, with a 12% false-negative rate of PET/CT detecting PALN metastasis, nodal staging surgery followed by tailored CRT resulted in an additional cost of $921 per patient, with an increase in effectiveness of 0.048 QALYs. Compared to pelvic CRT alone, the ICER for nodal staging surgery was $19,505/QALY (Table 3).

One-way sensitivity analyses were performed on selected variables in the model across the ranges specified in Table 4. In the base-case model, a 30% reduction in survival is assumed if patients undergo pelvic CRT despite the presence of occult PALN metastasis. As the true effect of unstaged PALN metastasis is unknown in LACC, the percentage reduction in survival was varied for sensitivity analysis. The model was relatively sensitive to changes in survival reduction in patients who undergo pelvic CRT despite the presence of occult PALN metastasis (cohort 2) compared to those who had nodal staging surgery followed by tailored CRT as a result of PALN metastasis (cohort 3). When the reduction in survival was less than 17%, the ICER per QALY saved increases to $50,000, and when the reduction in survival was less than 12%, the ICER increased to $100,000 per QALY saved. The model was insensitive to changes in the performance of PET/CT and postoperative complication rates when rates were varied over clinically reasonable ranges. Nodal staging surgery followed by tailored CRT was more cost-effective than pelvic CRT alone, as the ICER did not exceed $50,000/QALY so long as the false-negative rate for PET/CT is higher than 5%. If postoperative complication rates were below 30%, ICER did not exceed $60,000/QALY.

A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was conducted using a Monte Carlo simulation of 10,000 trials. The acceptability curve, depicted in Fig. 2, shows a comparison between the two strategies. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis demonstrates the robustness of the base-case results, with a 48%, 82%, and 91% probability of cost-effectiveness at the willingness-to-pay thresholds of $20,000/QALY, $40,000/QALY, and $60,000/QALY, respectively.

To date, there is no absolute threshold of cost-effectiveness that policy-makers will consider for a strategy to be acceptable. In the US, $50,000 per QALY is frequently cited as being cost-effective. The ICER threshold in South Korea has not been determined officially. The 'World Health Report 2002' suggests that an intervention that costs less than three times the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for each disability-adjusted life year is cost-effective. As GDP per capita in South Korea in 2011 was $21,539, a willingness-to-pay threshold of $60,000/QALY (around three times the Korean GDP per capita) is used to define a cost-effective strategy from the standpoint of resource utilization in the Korean healthcare system [2324].

In this study, a cost-effectiveness analysis was performed that compared two strategies LACC; the results showed that nodal staging surgery followed by tailored CRT is a cost-effective treatment option within clinically acceptable range of variables. To date, no studies have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of nodal staging surgery in the era of PET/CT.

A major limitation of our study is the lack of survival data for unstaged PALN metastasis in the model as no prospective trial has been performed that compares the outcomes of nodal staging followed by tailored CRT and pelvic CRT without surgical staging in the era of PET/CT. The base-case scenario assumes a 30% reduction in overall survival when patients undergo pelvic CRT despite the presence of occult PALN metastasis. Our model is clearly sensitive to changes in survival differences between patients who undergo pelvic CRT and those with who have nodal staging surgery in cases with occult PALN metastasis. Nodal staging surgery followed by tailored CRT is cost-effective (ICER <$60,000) when survival reduction falls within a clinically reasonable range. At the baseline false-negative rate for PET/CT detecting PALN metastasis (12%), a 15% reduction in the survival rate for patients with unstaged PALN metastasis indicates that the 5-year overall survival rate for strategy 2 is higher than for strategy 1 by approximately 1.7%. Although no randomized trials evaluate the role of surgical staging in the era of PET/CT, prospective studies suggest that nodal staging surgery followed by extended-field CRT provides survival gains for patients with PALN metastases measuring 5 mm or less metastases that would probably be missed by PET/CT [1225].

Other one-way sensitivity analyses show the robustness of our cost-effectiveness results. The proportion of cases of PALN metastasis showing no uptake on PET or PET/CT but proven by histologic analysis to be positive (false-negative rate) was 5% to 17%. Nodal staging surgery followed by tailored CRT is cost-effective for a wide range of false-negative rates for PET/CT detecting PALN metastasis. Moreover, morbidity following surgical staging should be considered together with possible perioperative and late adverse effects. Although we consider only lymphocele and lymphedema, an extraperitoneal approach is shown to reduce perioperative morbidity and particularly the incidence of RT-induced complications [26]. The incidence rates for lymphocele and lymphedema that require intervention following nodal staging surgery are within tolerable range (less than 10%) when performed by highly skilled surgeons [25]. Our model shows that nodal staging surgery is cost-effective with a wide range of postoperative complication rates.

If PET/CT shows negative findings for PALN metastasis, we assume that any occult PALN metastases (unstaged PALN) measure less than 5 mm at the time of surgical staging. Some showed that the survival rate for patients with PALN metastases measuring 5 mm or less (when treated with nodal staging surgery followed by extended-field CRT) is similar to that of women without PALN metastasis [12]. However, a considerable proportion of cases where PALN metastases measure more than 5 mm (6.8%) was found in a prospective trial despite negative uptake in PET/CT [25]. Gouy et al. [25] demonstrated that the event-free survival rate at 3 years in patients with PALN metastases measuring more than 5 mm was just 17%. For PALN involvement greater than 5 mm in particular, the survival gains from nodal staging surgery followed by extended-field CRT are not clear. Therefore, the survival outcome of nodal staging surgery followed by tailored CRT reported in this study may be overestimated.

Other limitations of this study include the assumption that there was no delay in the administration of definite CRT after nodal staging surgery. A major drawback of nodal staging surgery is the resultant delay in starting curative treatment, attributable to either an overburdened surgical schedule or postoperative morbidity [27].

Despite these limitations, our model provides an insight into how clinicians might approach treatment decisions for patients with LACC. Based on previous results, a considerable proportion of patients have PALN metastasis even when no uptake is found in PET/CT. Nodal staging surgery followed by extended-field CRT can be expected to improve survival outcomes in this subgroup without adding a significant economic burden.

In conclusion, nodal staging surgery before CRT is potentially cost-effective in clinically acceptable ranges for LACC when PET/CT shows no evidence of PALN metastasis. While definite data are needed to confirm our results, this study demonstrates the merit of incorporating nodal staging surgery in future prospective trials. This study opens up discussion of the possibility that nodal staging surgery may be cost-effective in the era of PET/CT. Prospective trials are warranted to transfer these results to guidelines.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Schematic model. CRT, chemoradiotherapy; EFRT, extended-field radiation therapy; PALN, para-aortic lymph node; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/computed tomography.

Fig. 2

Cost-effectiveness (CE) acceptability curve comparing two strategies. CRT, chemoradiotherapy.

Table 1

Clinical estimates

| Parameter | Baseline estimate | Range | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Utility | Lesnock et al. (2013) [14] | ||

| Radiation | 0.76 | ||

| Recovery | 0.86 | ||

| Acute GU | 0.68 | ||

| Chronic GU | 0.55 | ||

| Acute GI | 0.62 | ||

| Chronic GI | 0.63 | ||

| Survivor (after 1 year) | 0.90 | Ahn and Kim (2012) [21] | |

| Probabilities | Lesnock et al. (2013) [14] | ||

| Acute GI toxicity/pelvic | 0.08 | ||

| Acute GI toxicity/EFRT | 0.15 | ||

| Chronic GI toxicity/pelvic | 0.03 | ||

| Chronic GI toxicity/EFRT | 0.12 | ||

| Acute GU toxicity/pelvic | 0.02 | ||

| Acute GU toxicity/EFRT | 0.02 | ||

| Chronic GU toxicity/pelvic | 0.03 | ||

| Chronic GU toxicity/EFRT | 0.03 | ||

| False-negative rate for PALN metastasis, PET/CT | 0.12 | 0.05-0.15 | Gouy et al. (2013) [25] |

| Postoperative complication rate (lymphedema, lymphocele) | 0.03 | 0-0.3 | Gouy et al. (2013) [25] |

| 5-Year overall survival | |||

| PALN metastasis, fully staged, followed by extended-field CRT | 0.65 | 0.6-0.7 | Leblanc et al. (2007) [12] |

| PALN metastasis, unstaged, followed by pelvic CRT | 0.45* | 0.4-0.6 | Assumption |

| No PALN metastasis, followed by pelvic CRT | 0.65 | 0.6-0.7 | Rose et al. (2007) [10] |

Table 2

Costs incorporated into the model using claims data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service

Table 3

Cost-effectiveness analysis

| Variable | Strategy 1 | Strategy 2 | Difference | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness (QALY) | 3.755 | 3.803 | 0.048 | - |

| Total costs (US $) | 12,960 | 13,881 | 921 | 19,505 |

Table 4

One-way sensitivity analyses of selected variables

References

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Center (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Cervical Cancer [Internet]. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network;c2014. cited 2015 Jun 10. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#cervical.

2. Lai CH, Huang KG, Hong JH, Lee CL, Chou HH, Chang TC, et al. Randomized trial of surgical staging (extraperitoneal or laparoscopic) versus clinical staging in locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003; 89:160–167.

3. Gold MA, Tian C, Whitney CW, Rose PG, Lanciano R. Surgical versus radiographic determination of para-aortic lymph node metastases before chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Cancer. 2008; 112:1954–1963.

4. Brockbank E, Kokka F, Bryant A, Pomel C, Reynolds K. Pre-treatment surgical para-aortic lymph node assessment in locally advanced cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 3:CD008217.

5. Choi HJ, Ju W, Myung SK, Kim Y. Diagnostic performance of computer tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography or positron emission tomography/computer tomography for detection of metastatic lymph nodes in patients with cervical cancer: meta-analysis. Cancer Sci. 2010; 101:1471–1479.

6. Gouy S, Morice P, Narducci F, Uzan C, Gilmore J, Kolesnikov-Gauthier H, et al. Nodal-staging surgery for locally advanced cervical cancer in the era of PET. Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13:e212–e220.

7. Lee JY. Management of cervical cancer patients with isolated paraaortic lymph node metastases. J Gynecol Oncol. 2013; 24:382–383.

8. Eifel PJ, Winter K, Morris M, Levenback C, Grigsby PW, Cooper J, et al. Pelvic irradiation with concurrent chemotherapy versus pelvic and para-aortic irradiation for high-risk cervical cancer: an update of radiation therapy oncology group trial (RTOG) 90-01. J Clin Oncol. 2004; 22:872–880.

9. Keys HM, Bundy BN, Stehman FB, Muderspach LI, Chafe WE, Suggs CL 3rd, et al. Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:1154–1161.

10. Rose PG, Ali S, Watkins E, Thigpen JT, Deppe G, Clarke-Pearson DL, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized trial comparing concurrent single agent cisplatin, cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy, or hydroxyurea during pelvic irradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:2804–2810.

11. Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, Thigpen JT, Deppe G, Maiman MA, et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:1144–1153.

12. Leblanc E, Narducci F, Frumovitz M, Lesoin A, Castelain B, Baranzelli MC, et al. Therapeutic value of pretherapeutic extraperitoneal laparoscopic staging of locally advanced cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007; 105:304–311.

13. Lim MC, Bae J, Park JY, Lim S, Kang S, Seo SS, et al. Experiences of pretreatment laparoscopic surgical staging in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer: results of a prospective study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2008; 19:123–128.

14. Lesnock JL, Farris C, Beriwal S, Krivak TC. Upfront treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer with intensity modulated radiation therapy compared to four-field radiation therapy: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2013; 129:574–579.

15. Konski A, Watkins-Bruner D, Feigenberg S, Hanlon A, Kulkarni S, Beck JR, et al. Using decision analysis to determine the cost-effectiveness of intensity-modulated radiation therapy in the treatment of intermediate risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006; 66:408–415.

16. Jewell EL, Smrtka M, Broadwater G, Valea F, Davis DM, Nolte KC, et al. Utility scores and treatment preferences for clinical early-stage cervical cancer. Value Health. 2011; 14:582–586.

17. Asukai Y, Valladares A, Camps C, Wood E, Taipale K, Arellano J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in the second-line treatment of non-small cell lung cancer in Spain: results for the non-squamous histology population. BMC Cancer. 2010; 10:26.

18. Gold MR, Franks P, McCoy KI, Fryback DG. Toward consistency in cost-utility analyses: using national measures to create conditionspecific values. Med Care. 1998; 36:778–792.

19. Ernst EJ, Ernst ME, Hoehns JD, Bergus GR. Women's quality of life is decreased by acute cystitis and antibiotic adverse effects associated with treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005; 3:45.

20. El-Gazzaz G, Hull TL, Mignanelli E, Hammel J, Gurland B, Zutshi M. Obstetric and cryptoglandular rectovaginal fistulas: long-term surgical outcome; quality of life; and sexual function. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010; 14:1758–1763.

21. Ahn JH, Kim YH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of HPV vaccine. Seoul: National Evidence-based Coolaborating Agency;2012.

22. Yi JJ, Yoo WK, Kim SY, Kim KK, Yi SW. Medical expenses by site of cancer and survival time among cancer patients in the last one year of life. J Prev Med Public Health. 2005; 38:9–15.

23. World Health Organization. World health report. Geneva: World Health Organization;2002.

24. Eichler HG, Kong SX, Gerth WC, Mavros P, Jonsson B. Use of cost-effectiveness analysis in health-care resource allocation decision-making: how are cost-effectiveness thresholds expected to emerge? Value Health. 2004; 7:518–528.

25. Gouy S, Morice P, Narducci F, Uzan C, Martinez A, Rey A, et al. Prospective multicenter study evaluating the survival of patients with locally advanced cervical cancer undergoing laparoscopic paraaortic lymphadenectomy before chemoradiotherapy in the era of positron emission tomography imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:3026–3033.

26. Occelli B, Narducci F, Lanvin D, Querleu D, Coste E, Castelain B, et al. De novo adhesions with extraperitoneal endosurgical para-aortic lymphadenectomy versus transperitoneal laparoscopic para-aortic lymphadenectomy: a randomized experimental study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 183:529–533.

27. Hong DG, Park NY, Chong GO, Cho YL, Park IS, Lee YS. Survival benefit of laparoscopic surgical staging-guided radiation therapy in locally advanced cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2010; 21:163–168.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download