Abstract

Objective

To prospectively evaluate the feasibility, safety, and survival of laparoscopic surgical staging in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer.

Methods

From Oct 2001 to Jul 2006, a total of 83 consecutive patients were eligible for inclusion and underwent laparoscopic surgical staging.

Results

Three patients with intraoperative great vessel injury and 1 patient in whom the colpotomizer was unable to be inserted were excluded. Laparoscopic surgical staging was feasible in 95.2% (79/83). Immediate postoperative complications were noted in 12 (15.2%) patients. Prolonged complications directly related to operative procedures numbered 2 (2.5%), and were trocar site metastases. The mean time from surgery to the start of radiotherapy (RT) or concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) was 11 (5-35) days. All patients tolerated the treatment well and completed scheduled RT or CCRT without disruption of treatment and additional admission. The rate of modification of the radiation field after surgical staging was 8.9% (7/79). Five-year progression-free survival and overall survival (OS) rates were 79% and 89%, respectively. The OS of patients with microscopic lymph node metastases, which were fully resected, were comparable to those of patients without lymph node metastasis. However, the OS of patients with macroscopic lymph node metastases that were fully resected were poorer compared with those of patients without lymph node metastasis.

The current staging system for cervical cancer is based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) clinical staging system comprising of pelvic examination, cystoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, chest X-ray and IVP. Lymphatic and lymph node (LN) metastases are the most important metastatic pathways. LN status by surgical procedures was included in ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer.1,2 However, the clinical FIGO stage does not consider LN status.3 In clinical practice, treatment modalities and field have been influenced by imaging studies such as CT, MRI or PET in the management of cervical cancer.4 We reported previously the limitations of pretreatment imaging studies in predicting LN metastases, and showed that the sensitivity of pretreatment MRI and PET/CT was 30.3% and 57.6%, respectfully, compared to pathological diagnosis of LN.5 Radiotherapy planned on imaging studies may reveal two problems in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer. One is missing metastatic LN as a false negative result of the imaging studies, and the other is overtreatment as a false positive result of the imaging studies. Therefore, pathological confirmation by surgical staging is essential.6,7 Another possible benefit of surgical LN dissection is curative resection of bulky metastatic LN to improve therapeutic effect of radiotherapy.7-9

Transperitoneal and extraperitoneal abdominal approaches have been attempted since 1970 and 1980. But, these methods have not accepted as standard treatment modalities because of related morbidity and delay of radiotherapy.10-12 After Laparoscopic LN staging was introduced in 1990, the feasibility, low morbidity and no delay of radiotherapy for such a procedure have been reported.13-17

Laparoscopic LN staging was expected to maximize effect of radiotherapy by modifying radiotherapy field and by resection of bulky metastatic LN.18 This study was conducted to investigate the feasibility, morbidity and treatment modification by pretreatment laparoscopic surgical staging in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer.

This prospective clinical trial was performed to investigate the feasibility, morbidity and treatment modification in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer, from October 2001-July 2006. This study was approved by the institutional review board of National Cancer Center (#NCCCTS-02-025).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: untreated, histologically confirmed FIGO stage IB2-IVA (for stage IIA, maximal diameter of tumor was larger than 4 cm); age 20-75 years; no contraindications to surgical procedure; no evidence of distant metastases; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1; and provision of informed consent to participate in this procedure after the nature of the procedure had been fully explained. MRI and PET or PET/CT were performed preoperatively.

All patients underwent bowel preparation 2 day before surgery. Prophylactic antibiotics were given. All procedures were performed by gynecologic oncologic faculties, gynecologic oncologic fellows and residents. Peumoperitoneum was produced through a Veress needle, which was inserted below the umbilicus. A camera was inserted into the 11 mm sized umbilical port, and then full exploration of abdominal cavity was performed. Two 5 mm sized ports at both lower quadrants were inserted and another 5 mm sized port was inserted into the suprapubic area. Another 11 mm sized trocar was inserted into the left upper quadrant to manipulate the small intestine. Small endo-bags were used to prevent port site metastases. The port sites were irrigated with diluted potadine solution after experiencing port site metastases after laparoscopic surgical staging Apr. 2005. Operators dissected the LN to the contrary part of patients after identifying ureters. All para-aortic LNs were tried to dissected up to the inferior border of renal vein. The upper border of LN dissection was marked with endo-clips. Presacral LN was tried to dissected with preserving the hypogastric nerve. LNs were dissected systemically irrespective of LN enlargement. The peritoneum was left opened. JP drains were inserted into the pelvis to drain and monitor postoperative bleeding. Ports were removed after complete drainage of CO2 gas to avoid the chimney effect.

All patients were treated with 40-44 Gy external radiotherapy followed by intracavitary radiotherapy, high- dose-rate technique using iridium-192 source. Para-aortic LN area was irradiated only when pathologic LN metastases were confirmed. Patients received whole-pelvic irradiation. During external radiotherapy, all patients received chemotherapy: Cisplatin 40 mg/m2, weekly, 4-6 cycles. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (Version 11.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Eighty-four patients with locally advanced cervical cancer were candidates for laparoscopic LN staging. Three patients and 1 patient were excluded from this analysis because of vascular injury and inability to insert a colpotomizer, respectively. Full laparoscopic LN dissection was possible in 79 patients (95.2%). The characteristics of the patients who underwent laparoscopic LN dissection is described in Table 1. Median age was 48.0 (23-72). Body mass index 23.8±3.4 kg/m2, and 79.8% (63/79) patients were FIGO stage IIb, and 83.5% (66/79) patients were squamous cell carcinoma. Ten patients had a history of at least one prior abdominal surgery.

Table 2 lists the surgical results. The median duration of surgery was 230 minutes (145-490 minutes). The total number of LNs dissected was 2,962: 805 para-aortic LNs and 2,157 pelvic LNs. Mean number of LNs dissected per one patient was 38 (14-98): 10 (3-38) para-aortic LNs, and 27 (10-60) pelvic LNs. Metastases was noticed in 38 (48.1%) patients. Also, 31 (39.2%) patients had metastases limited to pelvis and 7 (8.9%) patients revealed para-aortic LN meta stasis with pelvic LN metastases. Para-aortic LN in one of two patients suggestive of metastases by preoperative image was pathologically proven metastasis. Six (7.8%) of 77 patients suggestive of no metastases by preoperative image had LN metastases in the para-aortic LN by pathologic diagnosis. The mean size of metastatic tumor in LNs was 15 mm (0.3-45 mm). Postoperative complications were noticed in 12 (15.2%) patients: silent lymphocele in 3 (3.8%), infected lymphocele in 1 (1.3%), lymphedema in 2 (2.5%), port site bleeding in 1 (1.3%), febrile morbidity in 1 (1.3%), ileus in 3 (3.8%), and wound infection in 1 (1.3%). Complications requiring surgical procedures and intensive care unit (ICU) care were did not develop until after 30 days except for one of three patients with ileus requiring laparoscopic adhesion lysis.

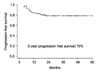

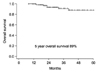

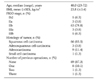

One (1.3%) patient with decreased renal function received radiotherapy only and 78 (98.7%) patients received concurrent chemotheradiotherapy (Table 3). Seven patients who had para-aortic LN metastases received extended-field radiotherapy. The median time from laparoscopic surgical staging to start of radiotherapy was 11 (5-35) days. Laparoscopic ovarian transposition was performed in 17 (21.5%) patients. Serum follicule-stimulating hormone (FSH) was checked in 13 (76.5%) patients, and 10 of 13 (76.9%) patients revealed FSH level of less than 40 mIU/ml. No metastases were observed in the transposed ovaries. Major complications related to radiotherapy were mild abdominal pain and diarrhea. However, neither interruption nor delay of radiotherapy was observed in all patients. Post-radiotherapy complications were observed in 62 (78.5%) cases: simple lymphocele in 16 (20.2%), infected lymphocele in 7 (8.9%), lymphedema in 22 (27.8%), dermato-lymphangitis in 6 (7.6%), post-radiotherapy rectal bleeding in 5 (6.3%), post-radiotherapy hemorrhagic cystitis in 2 (2.5%), deep vein thrombosis in 2 (2.5%), and port site metastases in 2 (2.5%). Median follow up period was 32 (8-60) months. Recurrence was noticed in 16 cases, and 6 patients died of disease. The 5-year progression free survival (PFS) and 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were 79% and 89%, respectively (Fig. 1, 2). When survival was compared by LN status, improved survival was noticed in patients with no LN metastases or microscopic LN metastases, compared to gross LN metastases (p=0.0332) (Fig. 3). Survival difference was not noticed in between patients with microscopic LN metastases and gross LN metastases (p=0.1710).

LN status is not considered in the FIGO staging system of cervical cancer. On the other hand, pathological diagnosis of LNs was one of factors to constitute the FIGO surgical staging system for endometrial cancer and ovarian cancer. However, LN metastases are also significant in cervical cancer as in endometrial cancer or ovarian cancer. In cervical cancer, LN metastases spread sequentially from the pelvic LN to para-aortic LN. Pelvic and para-aortic LN metastases were noticed 16.4% and 2.3% in Ib, 24.5% and 3.2% in IIb, and 26.7% and 6.7% in IIb cervical cancer.19 LN status is reported to be one of the most important factors for recurrence and survival in cervical cancer.20, 21

MRI is limited in differentiating metastatic lymphadenopathy from reactive LN hyperplasia.22 Although PET has revealed 85.7% sensitivity, 94.4% specificity, 92% accuracy in locally advanced cervical cancer,23 sensitivity is limited to 10% (1/10) in cases without LN enlargement on the MRI.24 Therefore, laparoscopic surgical staging may be a valid substitute to overcome such inaccuracies.

Treatment plans for concurrent chemoradiotherapy are determined not by surgical LN staging but such inaccurate imaging modalities. Surgical staging offers accurate information for radiotherapy based on pathological diagnosis. If para-aortic LN metastases are confirmed, extended-field radiotherapy may be offered to the area. If LN metastases were excluded by surgical staging, complications related to radiotherapy at para-aortic area may be avoided. Fagotti et al. analyzed 5 clinical studies for laparoscopic surgical staging and reported 11-25% para-aortic LN metastases in patients with FIGO stage IB-IV cervical cancer.16 In the present study, 1 of 2 patients with LN enlargement in the pretreatment imaging studies revealed pathological LN metastases, and 6 of 77 patients with no evidence of LN enlargement in the pretreatment image studies revealed pathological LN metastases. Therefore, treatment was modified in 7 of 79 (8.9%) patients with cervical cancer in the present study.

The important issues for surgical staging may be postoperative morbidity and delay or interruption of radiotherapy. Introducing laparoscopic surgery to surgical staging minimizes postoperative morbidity and duration of hospitalization. 25 After Childers et al. reported the feasibility of laparoscopic surgical staging with acceptable morbidity and no delay of radiotherapy,25 several investigators further performed laparoscopic surgical staging.15-17 Laparoscopic surgical staging minimized intra-abdominal adhesions and decreases bowel morbidity. Smaller incisions in laparoscopy compared to laparotomy enabled short-term recovery and minimized immune suppression.26 In the present study, the median duration from laparoscopic surgical staging to radiotherapy was 11 (5-35) days, interruption and delay of radiotherapy were not identified.

Postoperative bowel adhesion after surgical staging has been considered to be a cause of bowel complications. Table 2 reveals 12 (15.2%) complications including 3 (3.8%) cases of ileus. Two cases were managed by medical treatment, and one case required laparoscopic adhesion lysis. Table 3 reveals the complications that developed during follow up period after radiotherapy. Complications directly related to surgical staging were port site metastases in 2 (2.5%) cases. After previously experiencing port site metastases, all port sites, especially those used for LN harvesting, were irrigated with diluted potadine solution.27 Other measures conducted to minimize port site metastases were a vertical insertion of port to abdominal wall, minimizing port movement and avoid chimney effect.

Other issues to be discussed are the number of LN harvested and time of operative procedure. In the present study, surgically removed LN of 38 (14-98) per patient were comparable to the results of laparotomy or laparoscopic surgical staging by several investigators.13,16,17,28,29 Median time for operative procedures was 230 (145-490) minutes, and this decreased after gradual accumulation surgical experience.17

To cure 90% of the 2 cm sized cervical cancer, 6,000 cGy radiotherapy was required.30 Therefore, metastatic LN of more than 2 cm are difficult to treat with radiotherapy only, and surgical resection of huge metastatic LN may enhance the radiotherapy effect. The benefits of surgical resection of metastatic LN in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer have been previously described.6,7,31,32 In the present study, survival was significantly decreased in patients with gross LN metastases, compared to microscopic or no LN metastases (Fig. 3). Caution is required to interpret such results, because several different surgical methods may result in diverse results: transperitoneal or retroperitoneal and systemic LN dissection or selective LN dissection.

Another benefit of laparoscopic surgical staging is preservation of ovarian function by ovarian transposition. Morice et al.33 reported that ovarian transposition may be performed in selected patients with no extrauterine disease, no uterine corpus disease, no lymphovascular invasion, under the age of 40 years, and small cervical lesion of less than 3 cm. In the present study, we performed ovarian transposition in 17 young patients who were without extrauterine disease. Preoperative counseling regarding the benefits, such as prevention or delay of menopause, and the risks, such as metastasis or recurrence of ovarian transposition is essential. In the present study, ovarian transpositions was performed in 17 patients. Ovarian function was preserved in 10 of 13 (76.9%) patients, whose serum FSH were checked. No recurrence was identified.

Survival gain through treatment modification by surgical staging was uncertain.16,34-36 Only one prospective randomized clinical trial performed by Lai et al. reported 25% pathological LN metastases, and only resulted in decrease of PFS.28 However, this study has two weak points, such as treatment delay of 3 weeks and shortage of number of harvested LN. Further large randomized prospective clinical trials to reveal possible survival benefits, and especially to identify a subgroup who would benefit from laparoscopic surgical staging will be required. Laparoscopic surgical staging must be limited to clinical trial until there is clear evidence of survival gain.

In conclusion, laparoscopic surgical staging in locally advanced cervical cancer is feasible and safe with acceptable morbidity. But, survival gain with such procedures was not confirmed. So, large prospective randomized clinical trials will be needed to confirm any survival effects.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Progression free survival underwent laparoscopic surgical staging in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer.

Fig. 2

Overall survival underwent laparoscopic surgical staging in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer.

Fig. 3

Overall survival underwent laparoscopic surgical staging in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer by lymph node status.

Table 1

Patient characteristics underwent laparoscopic surgical staging in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer

Notes

References

1. Boronow RC, Morrow CP, Creasman WT, Disaia PJ, Silverberg SG, Miller A, et al. Surgical staging in endometrial cancer: Clinical-pathologic findings of a prospective study. Obstet Gynecol. 1984. 63:825–832.

2. Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Quinn MA, Benedet JL, Creasman WT, et al. Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 6th annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006. 95:Suppl 1. S161–S192.

3. Benedet JL, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Beller U, Creasman WT, Heintz AP, et al. Carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003. 83:Suppl 1. 41–78.

4. Amendola MA, Hricak H, Mitchell DG, Snyder B, Chi DS, Long HJ 3rd, et al. Utilization of diagnostic studies in the pretreatment evaluation of invasive cervical cancer in the United States: Results of intergroup protocol ACRIN 6651/GOG 183. J Clin Oncol. 2005. 23:7454–7459.

5. Choi HJ, Roh JW, Seo SS, Lee S, Kim JY, Kim SK, et al. Comparison of the accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the presurgical detection of lymph node metastases in patients with uterine cervical carcinoma: A prospective study. Cancer. 2006. 106:914–922.

6. Vasilev SA. A modified incision and technique for total retroperitoneal access and lymph node dissection. Gynecol Oncol. 1995. 56:226–230.

7. Cosin JA, Fowler JM, Chen MD, Paley PJ, Carson LF, Twiggs LB. Pretreatment surgical staging of patients with cervical carcinoma: The case for lymph node debulking. Cancer. 1998. 82:2241–2248.

8. Kim PY, Monk BJ, Chabra S, Burger RA, Vasilev SA, Manetta A, et al. Cervical cancer with paraaortic metastases: Significance of residual paraaortic disease after surgical staging. Gynecol Oncol. 1998. 69:243–247.

9. Hacker NF, Wain GV, Nicklin JL. Resection of bulky positive lymph nodes in patients with cervical carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1995. 5:250–256.

10. LaPolla JP, Schlaerth JB, Gaddis O, Morrow CP. The influence of surgical staging on the evaluation and treatment of patients with cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1986. 24:194–206.

11. Lagasse LD, Creasman WT, Shingleton HM, Ford JH, Blessing JA. Results and complications of operative staging in cervical cancer: Experience of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 1980. 9:90–98.

12. Berman ML, Lagasse LD, Watring WG, Ballon SC, Schlesinger RE, Moore JG, et al. The operative evaluation of patients with cervical carcinoma by an extraperitoneal approach. Obstet Gynecol. 1977. 50:658–664.

13. Vidaurreta J, Bermudez A, di Paola G, Sardi J. Laparoscopic staging in locally advanced cervical carcinoma: A new possible philosophy? Gynecol Oncol. 1999. 75:366–371.

14. Schlaerth JB, Spirtos NM, Carson LF, Boike G, Adamec T, Stonebraker B. Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy followed by immediate laparotomy in women with cervical cancer: A gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2002. 85:81–88.

15. Possover M, Krause N, Plaul K, Kuhne-Heid R, Schneider A. Laparoscopic para-aortic and pelvic lymphadenectomy: Experience with 150 patients and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1998. 71:19–28.

16. Fagotti A, Fanfani F, Longo R, Legge F, Mari A, Gagliardi ML, et al. Which role for pre-treatment laparoscopic staging? Gynecol Oncol. 2007. 107:S101–S105.

17. Chung HH, Lee S, Sim JS, Kim JY, Seo SS, Park SY, et al. Pretreatment laparoscopic surgical staging in locally advanced cervical cancer: Preliminary results in Korea. Gynecol Oncol. 2005. 97:468–475.

18. Querleu D, Dargent D, Ansquer Y, Leblanc E, Narducci F. Extraperitoneal endosurgical aortic and common iliac dissection in the staging of bulky or advanced cervical carcinomas. Cancer. 2000. 88:1883–1891.

19. Lim M, Lee S, Park S, Kim S. Clinicopathologic analysis and prognosis of uterine cervical cancer. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2005. 48:302–313.

20. Alvarez RD, Potter ME, Soong SJ, Gay FL, Hatch KD, Partridge EE, et al. Rationale for using pathologic tumor dimensions and nodal status to subclassify surgically treated stage IB cervical cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1991. 43:108–112.

21. Averette HE, Dudan RC, Ford JH Jr. Exploratory celiotomy for surgical staging of cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972. 113:1090–1096.

22. Rockall AG, Sohaib SA, Harisinghani MG, Babar SA, Singh N, Jeyarajah AR, et al. Diagnostic performance of nanoparticle-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of lymph node metastases in patients with endometrial and cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005. 23:2813–2821.

23. Lin WC, Hung YC, Yeh LS, Kao CH, Yen RF, Shen YY. Usefulness of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to detect para-aortic lymph nodal metastasis in advanced cervical cancer with negative computed tomography findings. Gynecol Oncol. 2003. 89:73–76.

24. Chou HH, Chang TC, Yen TC, Ng KK, Hsueh S, Ma SY, et al. Low value of [18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in primary staging of early-stage cervical cancer before radical hysterectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2006. 24:123–128.

25. Childers JM, Hatch K, Surwit EA. The role of laparoscopic lymphadenectomy in the management of cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1992. 47:38–43.

26. Decker D, Schondorf M, Bidlingmaier F, Hirner A, von Ruecker AA. Surgical stress induces a shift in the type-1/type-2 T-helper cell balance, suggesting down-regulation of cell-mediated and up-regulation of antibody-mediated immunity commensurate to the trauma. Surgery. 1996. 119:316–325.

27. Park JY, Lim MC, Lim SY, Bae JM, Yoo CW, Seo SS, et al. Port-site and liver metastases after laparoscopic pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection for surgical staging of locally advanced cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008. 18:176–180.

28. Lai CH, Huang KG, Hong JH, Lee CL, Chou HH, Chang TC, et al. Randomized trial of surgical staging (extraperitoneal or laparoscopic) versus clinical staging in locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003. 89:160–167.

29. Possover M, Krause N, Kuhne-Heid R, Schneider A. Value of laparoscopic evaluation of paraaortic and pelvic lymph nodes for treatment of cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 178:806–810.

30. Wharton JT, Jones HW 3rd, Day TG Jr, Rutledge FN, Fletcher GH. Preirradiation celiotomy and extended field irradiation for invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Obstet Gynecol. 1977. 49:333–338.

31. Morice P, Castaigne D, Pautier P, Rey A, Haie-Meder C, Leblanc M, et al. Interest of pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy in patients with stage IB and II cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1999. 73:106–110.

32. Potish RA, Downey GO, Adcock LL, Prem KA, Twiggs LB. The role of surgical debulking in cancer of the uterine cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989. 17:979–984.

33. Morice P, Haie-Meder C, Pautier P, Lhomme C, Castaigne D. Ovarian metastasis on transposed ovary in patients treated for squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: Report of two cases and surgical implications. Gynecol Oncol. 2001. 83:605–607.

34. Eifel PJ, Winter K, Morris M, Levenback C, Grigsby PW, Cooper J, et al. Pelvic irradiation with concurrent chemotherapy versus pelvic and para-aortic irradiation for high-risk cervical cancer: An update of radiation therapy oncology group trial (RTOG) 90-01. J Clin Oncol. 2004. 22:872–880.

35. Grigsby PW, Heydon K, Mutch DG, Kim RY, Eifel P. Long-term follow-up of RTOG 92-10: Cervical cancer with positive para-aortic lymph nodes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001. 51:982–987.

36. Rotman M, Pajak TF, Choi K, Clery M, Marcial V, Grigsby PW, et al. Prophylactic extended-field irradiation of para-aortic lymph nodes in stages IIB and bulky IB and IIA cervical carcinomas. Ten-year treatment results of RTOG 79-20. Jama. 1995. 274:387–393.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download