Abstract

We report here a rare case of mesenteric Castleman's disease presenting as a mesenteric mass. A 13-year-old female child was admitted to our hospital complaining of intermittent vague abdominal pain. She had hypochromic anemia, thrombocytosis and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Ultrasonography and computed tomography indicated an intraabdominal mass might represent a lymphoma or gastrointestinal stromal tumor or leiomyoma, but the definitive preoperative diagnosis couldn't be confirmed. The surgical resection of the mass revealed the mesenteric hyaline vascular-type Castleman's disease.

Castleman's disease is rare lymphoproliferative disorder stemming from an unknown etiology, and it is characterized by giant lymph node hyperplasia and a non-malignant course. This disease usually occurs in the mediastinum, lung, neck, axilla, pelvis and retroperitoneum, but mesenteric Castleman's disease is very rarely seen. The clinical presentation is varied, the diagnosis is difficult and optimum management is still unknown. We report here our experience of mesenteric Castleman's disease in a 13-year old female child.

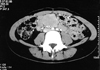

A 13-years old female child was admitted to the Korea University Guro Hospital presenting with intermittent left lower quadrant abdominal pain. On the physical examination, there was 5-cm sized palpable mass at the left lower abdominal quadrant, and the abdomen was without tenderness. The initial laboratory testing showed anemia (a hemoglobin level of 9.6g/dl and a hematocrit of 29.9%), thrombocytosis (platelet: 874K/µl) and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 130 mm/hr. The chest X-ray is normal. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a 3.2×4 cm sized hypoechoic mass lesion with focal peripheral vascularity (Fig. 1). No organomegaly was observed, and further investigations showed the normal level of gammaglobulin. The radiologist thought this mass might be a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) or a lymphoma. To gather more information, a computerized tomography (CT) scan was performed. The CT scan revealed a well circumscribed 4×3.5 cm sized, soft-tissue density, lobulated round mass in the mid-abdominal cavity (Fig. 2). With the CT scan findings, this mass was suspected to be a small bowel stromal tumor, Castleman's disease or lymphoma; therefore, we opted for surgery to get the definite diagnosis and treatment. On the operative field, the egg shaped mass was located at the root of the small bowel mesentery and it measured 5.0×4.5×4.0 cm in size. It was hard and surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule (Fig. 3A). On sectioning, the cut surface showed as a well defined homogenous brownish mass with multifocal whitish foci (Fig. 3B). On histopathologic examination, this mass showed lymphoid follicles separated by bands of connective tissue with centrally located thickened blood vessels, and it was compatible with the hyaline vascular type of Castleman's disease (Fig. 4A, 4B). The patient had an uneventful postoperative course. Her anemia, thrombocytosis and increased ESR all improved at the 3-month follow up.

Castleman's disease was first described by Dr. Benjamin Castleman in 1956 when he described a group of patients with large thymoma-like masses in the anterior mediastinum.1 Although it usually involves the mediastinum, extrathoracic lesion have been reported in the neck, axilla, shoulder region, pelvis, pancreas, nasopharynx and retroperitoneum, but finding Castleman's disease located in mesentery is a very rare event.

The etiology of Castleman's disease is unknown, but there are several hypotheses involving chronic low-grade inflammation, a hamartomatous process, an immunodeficiency state and autoimmunity disorder that have been proposed as likely pathogenetic machanisms.1-4

Castleman's disease can be classified into two types. The first is designated as the hyaline-vascular or angiofollicular type, and it shows small hyaline follicles and intrafollicular capillary proliferation. This type is present in 90% of the patients with Castleman's disease and it is generally seen in the localized cases, and it may present with fever and fatigue, but it is usually asymptomatic.

The other type is the plasma cell type, which less common than the hyaline-vascular type. This plasma cell type is systemic, symptomatic and characterized by fever, sweating, weight loss, anemia, an elevated sedimentation rate and hypergammaglobulinemia.5

The radiologic findings of Castleman's disease are non-specific, and the radiologic study without a pathologic report is not enough for a definite diagnosis. Computer assisted tomographic scan will show a well-defined soft tissue density, and the hyaline vascular type is more contrast-enhanced than the plasma cell type.6 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a low intensity mass on T-1 weighted images and a higher signal intensity on T-2 weighted images.7 The differential diagnosis to distinguish it from lymphoma, leiomyoma, and leiomyosarcoma must be performed.

Surgery is the choice of treatment, and it is also necessary for diagnosis in localized Castleman's disease. Radiation or chemotherapy is may be helpful for treatment, but it is not curative.8,9 Because Castleman's disease has a benign prognosis, if complete resection is difficult, partial resection may be helpful. Extended surgery for Castleman's disease is not needed for treatment, and the physician's extensive pre-operative diagnostic effort is required. This rare and benign disease should therefore be added to the list of disease in the differential diagnosis of mesenteric masses.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

CT scan of the patient shows a well-circumscribed intra-abdominal mass of soft tissue density at the small bowel mesentery.

Fig. 3

A. Macroscopically, the mass was egg shaped, and it measured 5.0×4.5×4.0 cm in size. B. The cut surface showed a well defined homogenous brownish mass with multifocal whitish foci.

Fig. 4

A. On histopathologic examination, lymphoid follicles with centrally located, thick blood vessels and interfollicular nodular hyalinizing fibrosis (hematoxylin and eosin, 100×). B. A lymphoid follicle containing centrally located blood vessels with deposits of hyalin (hematoxylin and eosin, 200×).

References

1. Castleman B, Iverson L, Menendez VP. Localized mediastinal lymph node hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer. 1956. 9:822–830.

2. Keller AR, Hochholzer L, Castleman B. Hyaline-vascular and plasma-cell types of giant lymph node hyperplasia of the mediastinum and other locations. Cancer. 1972. 29:670–683.

3. Lowenthal DA, Filippa DA, Richardson ME, Bertoni M, Straus DJ. Generalized lymphadenopathy with morphologic features of Castleman's disease in HIV-positive man. Cancer. 1987. 60:2454–2458.

4. Frizzera G. Castleman's disease and related disorders. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988. 5:346–364.

5. Seco JL, Velasco F, Manuel JS, Serrano SR, Tomas L, Velasco A. Retroperitoneal Castleman's disease. Surgery. 1992. 112:850–855.

6. Demirpolat G, Pourbagher A, Hekimgil M, Elmas N, Kitis O, Korkut M, et al. Mesenteric Castleman's disease: case report. Abdom Imaging. 2000. 25:551–553.

7. Bartkowski DP, Ferrigni RG. Castleman's disease: an unusual retroperitoneal mass. J Urol. 1988. 139:118–120.

8. Chronowski GM, Ha CS, Wilder RB, Cabanillas F, Manning J, Cox JD. Treatment of unicentric and multicentric Castleman's disease and the role of radiotherapy. Cancer. 2001. 92:670–676.

9. Bjarnason I, Cotes PM, Knowles S, Reid C, Wilkins R, Peters TJ. Giant lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman's disease) of the mesentery. Observations on the associated anemia. Gastroenterology. 1984. 87:216–223.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download