Abstract

Objective

The goal of this study is to compare the overall quality of film mammograms taken according to the Korean standards with the American College of Radiology (ACR) standard for clinical image evaluation and to identify means of improving mammography quality in Korea.

Materials and Methods

Four hundred and sixty eight sets of film mammograms were evaluated with respect to the Korean and ACR standards for clinical image evaluation. The pass and failure rates of mammograms were compared by medical facility types. Average scores in each category of the two standards were evaluated. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was used to identify an optimal Korean standard pass mark by taking the ACR standard as the reference standard.

Results

93.6% (438/468) of mammograms passed the Korean standard, whereas only 80.1% (375/468) passed the ACR standard (p < 0.001). Non-radiologic private clinics had the lowest pass rate (88.1%: Korean standard, 71.8%: ACR standard) and the lowest total score (76.0) by the Korean standard. Average scores of positioning were lowest (19.3/29 by the Korean standard and 3.7/5 by the ACR standard). A cutoff score of 77.0 for the Korean standard was found to correspond to a pass level when the ACR standard was applied.

Breast cancer is the second most common female cancer in Korea with increasing incidences (1, 2). Screening mammography for the early detection of breast cancer is the only method known to reducing mortality from breast cancer and inadequate mammogram quality can miss out on early breast cancer or lead to misdiagnosis (3). Furthermore, mammographic sensitivity in Korean women is less than that in Western women, because the frequency of dense mammograms is much greater among Korean women (4). Hence, high quality mammography is crucial for successful breast cancer detections. Stringent regulations and adequate education of personnel are essential to achieve high quality mammographic images, and in advanced countries, voluntary or mandatory mammography accreditation programs have already been established (5).

The Mammography Accreditation Program of the American College of Radiology (ACR) was initially developed as a voluntary program in 1987 in response to inadequate qualities (6, 7), and in 1992, the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) was established to standardize and improve the quality of mammography (7). This act mandates that all mammography facilities meet the minimum quality standards for personnel, equipment, and recordkeeping (7). After the regulations of the MQSA were applied, a remarkable improvement in quality was achieved (7, 8).

The Korean Society of Breast Imaging has continuously been studied and promoted for the education and quality control of mammography, and in 2001, they published a mammography quality control manual (9). In January 2003, 'regulations on the installation and management of special medical equipment' was enacted, and from December 2004 the Korean Institute for Accreditation of Medical Image (KIAMI), which was commissioned by the Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare, has conducted quality control tests on magnetic resonance, computed tomography, and mammography (10). To become an accredited facility, minimum requirements for the personnel, facility, and recordkeeping must all be satisfied. Documentation reviews are performed annually and a detailed inspection is conducted on the third year.

However, we have concerns for the unsatisfactory mammograms taken by other clinics and referred to our hospital despite that they passed the Korean standard for clinical image evaluations. Therefore, repeated mammography should be performed.

This study was undertaken to compare the overall quality of mammographic films taken according to the Korea standards along with the ACR standards for clinical image evaluations and to identify means of improving mammographic quality.

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this retrospective study. The requirement for informed consent was waived.

This study was conducted using film mammograms submitted either to KIAMI for accreditation purposes or to the four university hospitals (located in the different Korean provinces) by other medical facilities for review purposes between December 2007 and March 2008. The latter mammograms were of patients whom were referred to one of the four university hospitals for breast examinations. We analyzed the selected clinical images submitted to KIAMI for accreditations and random images were used in clinical practices to define the status of mammography quality in Korea. The number of mammogram sets per medical facility was less than five. One set of mammograms included standard craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique views. Copied film mammograms, mammograms of patients who had undergone breast surgery or were unable to pose properly due to disability, and mammograms of patients with huge breast masses were excluded. A total of 468 sets of mammograms (148 sets from KIAMI and 320 sets from university hospitals nationwide) from 260 medical facilities were collected. Specifically, there were 17 sets from 13 general hospitals (hospitals with more than 9 specialties and more than 100 beds), 62 sets from 42 hospitals (hospitals with 30-100 beds), 106 sets from 63 radiologic private clinics, 202 sets from 115 non-radiologic private clinics and 81 sets from 27 associations for health promotion (AHPs). General hospitals and radiologic private clinics have full-time radiologists, whereas other hospitals and AHPs usually have full-time radiologists. On the other hand, non-radiologic private clinics employ freelance radiologists.

Six radiologists with more than 5 years of specialized breast imaging experiences, performed clinical image evaluations on mammograms according to the Korean (Figs. 1, 2) and ACR standards (11) on the same day. Orders of the evaluations were randomized with respect to the two different standards. After the evaluation according to the two standards for one set of mammograms, the next evaluation for another set was being performed. The reviewers understood the types of medical facilities performing mammograms in about half of the cases. Mammograms submitted to KIAMI for accreditation purposes were evaluated by two radiologists at KIAMI and mammograms of referred patients were evaluated by four radiologists in their respective university hospitals. All six radiologists had worked as review physicians in KIAMI since 2004, had undergone regular training sessions (more than once a year), and had responsibilities as training special medical equipment managers.

According to the Korean standards, the following categories were used for clinical image evaluations: examination identification (perfect score = 9), positioning (MLO view) (perfect score = 29), positioning (CC view) (perfect score = 20), compression (perfect score = 10), contrast/exposure (perfect score = 12), noise/artifact (perfect score = 14), and etcetera (perfect score = 6). Failure is defined as a total score of less than 60 out of 100. The items assessed in each of these seven categories are listed in Fig. 2 (12).

The same images were evaluated according to the ACR standards, which involve the following eight categories: positioning, compression, contrast, noise, artifact, exposure, sharpness, and examination identification. Image quality was rated using a five-point scale (1 = severe deficiency, 2 = major deficiency, 3 = minor deficiency, 4 = good, 5 = best). For each of the eight categories, specific deficiencies, if any, were recorded as described by Bassett et al. (11). Failure was defined as a score of 1 or 2 in a single category or a score of 3 in multiple categories. However, isolated artifacts or image-labeling deficiencies do not contribute to failure.

Pass and failure rates determined by using the two standards were compared for all medical facilities and by facility type using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test.

In clinical image evaluations based on the Korean standard, average scores for medical facility types were compared by ANOVA test. In addition, average scores of the seven image quality categories and of the items in each of the seven categories were evaluated.

In clinical image evaluation based on the ACR standard, the average scores were determined for the eight image quality categories. For mammograms that failed to meet the ACR standard, frequencies of image quality categories with a score of 1 or 2 were calculated. The specific types and frequencies of deficiencies within each of the eight categories were also evaluated (11).

The Korean and ACR standards were compared accordingly. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to identify the optimal Korean standard pass mark when the ACR standard was regarded as the reference standard.

Statistical significance was accepted for p values less than 0.05. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc version 12.1.4 (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium).

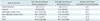

Among the 468 sets of mammograms, 93.6% (438/468) passed and 6.4% (30/468) failed the Korean standard, whereas 80.1% (375/468) passed and 19.9% (93/468) failed the ACR standard, and these pass rates were significantly different (p < 0.001). The pass rates of the two standards and average total Korean standard scores are summarized by medical facility type in Table 1.

The average total score of the 468 sets of mammograms was 79.6, and total scores ranged from 32 to 99. There were 29 sets with a total score of < 60, 44 with a total score of 60-69, 119 with a total score of 70-79, 193 with a total score of 80-89, and 83 with a total score of 90-100. Average total scores by medical facility type are summarized in Table 1. General hospitals and AHPs had significantly higher average total scores than non-radiologic private clinics (p < 0.001).

Average scores for image quality categories were as follows: 7.0/9 for examination identification, 19.3/29 for positioning (in MLO view), 17.7/20 for positioning (in CC view), 9.0/10 for compression, 9.8/12 for contrast/exposure, 11.1/14 for noise/artifact, and 5.7/6 for etcetera. Regarding criteria items within the categories, the average scores for punctate within artifact, for technologist's name within examination identification, and for inframammary fold within positioning in MLO view were lowest (0.2/2, 0.2/1, and 1.2/5 respectively).

Analysis by medical facility type resulted in a pass rate of 100% (17/17) for general hospitals, 95.1% (77/81) for AHPs, 84.9% (99/106) for radiologic private clinics, 74.2% (46/62) for hospitals, and of 71.8% (145/202) for non-radiologic private clinics. The pass rates of general hospitals and AHPs were significantly greater than those of hospitals and non-radiologic private clinics (p < 0.001).

Average scores for the eight image categories were: 3.7 for positioning, 4.1 for compression, 4.1 for contrast, 4.1 for exposure, 4.6 for noise, 4.4 for sharpness, 3.9 for artifact, and 3.8 for examination identification. Of the 93 mammograms that failed the ACR standard, 72 mammograms failed due to a score of 1 or 2 in a single category and 21 failed for a score of 3 in multiple categories. The frequencies of categories with a score of 1 or 2 were 51 (67.1%) for positioning, 24 (30.3%) for exposure, 19 (23.7%) for compression, 18 (22.4%) for contrast, and 8 (9.2%) for sharpness. Table 2 summarized specific deficiencies in image quality categories which deemed serious enough to lead to failure. No serious problem or specific deficiency related to image noise was identified.

All of the 30 sets of mammograms (6.4%, 30/468) that failed the Korean standard also failed the ACR standard, and 63 sets of mammograms that passed the Korean standard failed the ACR standard (Fig. 3). Of these 63 sets, 44 mammograms failed due to a score of 1 or 2 in a single category, and 19 failed due to a score of 3 in multiple categories. Of these 44 sets of mammograms with a severe or major deficiency, the frequencies of categories with a score of 1 or 2 were 29 (65.9%) for positioning, 15 (34.1%) for exposure, 9 (20.5%) for compression, 9 (20.5%) for contrast, and 3 (6.8%) for sharpness.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis revealed that a total score of 77.0 was optimal for the Korean standard pass mark when the ACR standard was regarded as the reference standard (Fig. 4). The independent samples t-test showed that all scores in the Korean standard categories were significantly related to the pass and failure of the ACR standard (p < 0.003).

In Korea, individual mammography screening has become popular since the mid-1990s when the National Health Insurance decided to cover half the costs of cancer screening (13). Today, screening or diagnostic mammography is conducted on thousands of women each year and the number increases steadily. Evaluation methods ensure that high quality images consistently produced are critical to the success of screening programs. Two sets of guidelines, that is, ACR and the European Commission (EU) guidelines, have been made available to standardize mammographic image evaluations (14). The EU guidelines contain criteria for each category of image assessment but general judgments are subjective. On the other hand, the criteria in the ACR guidelines are individually scored and awarded either a pass or a fail (11, 14). Therefore, we compared the Korean and ACR standards.

Before 'regulations on the installation and management of special medical equipment' were enacted in Korea, Lee et al. (15) reported that 64 of 371 (17.3%) mammograms failed to pass the Korean clinical image evaluation standards, and according to Moon et al. (16), 217 of 598 (36.3%) mammograms failed to pass the modified ACR standard. In the present study, 30 of 468 (6.4%) mammograms failed the Korean standard and the average total score was 79.6, which exceeded the pass mark. However, according to the ACR standards, 93 of the 468 (19.9%) mammograms failed. These results indicate that a marked improvement in quality has been achieved since regulations were introduced.

However, failure rates were obviously different for the two standards (6.4% and 19.9%), and the reduction degree in failure rates since regulations were introduced according to the ACR standard (36.3% to 19.9%) was less than that of the Korean standard (17.3% to 6.4%). This suggests that some mammographic images would not be satisfactory for the detection of early breast cancer despite passing the Korean standards, although the overall image quality of mammography was improved.

In a report issued by Moon et al. (16), before the quality control regulations were introduced, poor images were found with increasing orders of frequency, at university hospitals (8.9%), radiologic private clinics (38.2%), hospitals (42.6%), non-radiologic private clinics (47.7%), and AHPs (47.8%). In a study conducted by Lee et al. (15), the failure rate of non-radiologic clinics was relatively high (25.5%) which is similar to our results. In the present study, non-radiologic private clinics had the lowest average total score (score of 76.0) according to the Korean standard and the highest failure rate (28.2%) according to the ACR standard. Our findings show that high levels of quality control have been reached although non-radiologic private clinics without full-time radiologists found it difficult to improve mammographic image qualities. These results indicate that part-time radiologists should be encouraged to react to poor mammograms and that regular education programs should be provided for radiologic technologists in non-radiologic private clinics.

Bassett et al. (11) reported that among 2341 mammography units, 1034 (44%) failed the ACR clinical image evaluation. Of the 6128 categories were cited by reviewers as deficient, and common problems associated with clinical image quality were: positioning (20%, 1250/6128), exposure (15%, 944/6128) and compression (14%, 887/6128). Moon et al. (16) reported that that among 598 mammograms, 217 (36.3%) failed the modified ACR clinical image evaluation. Serious problems were associated with positioning in 23.7% (142/598), examination identification in 5.7% (34/598), and contrast in 4.2% (25/598). According to Lee et al. (15), the average score for positioning was 33.9/49 (69.2%) and the average scores for contrast and exposure were 2.9/4 (72.5%) and 3.7/6 (61.7%), respectively, which were lower than those of other categories. In the present study, the average score for positioning was 19.3/29 (in MLO view) for the Korean standard and 3.7/5 for the ACR standard, and these were the lowest scores for both standards. Moreover, according to the ACR standard, positioning was one of the most frequent categories with serious problems. Although this suggests that positioning is a difficult category, we believe that more training of practicing radiologic technologists is required.

In this study, when the ACR standard was regarded as the reference standard, the cutoff point for the Korean standard by ROC analysis was a score of 77.0, which substantially exceeds the present pass mark of 60. This difference is partially due to the failure rate given to severe or major deficiencies according to the ACR standard, whereas low scores within a category could still result in a pass for the Korean standard. In fact, of 63 mammograms that passed the Korean standard but failed the ACR standard, 44 (70.0%) mammograms failed due to a score of 1 or 2 in a single category. It would be helpful if the pass mark is increased; or, if the penalty is increased for a severe deficiency; or, considering very low score within a single category as a failure.

In 2009, the number of mammography units was about 2400 in Korea, these included film, computed radiography and digital mammography units (17). In our study, the number of mammography units included was 260, which was 10% more. Thus, it is believed that this study reflects the current status of film mammography quality in Korea more accurately than previous studies (15, 16).

However, this study has the following limitations. The first concerns inter-observer variability. Images were examined individually by reviewers, and rating methods are somewhat subjective and solely dependent on individual's understanding of the scale, knowledge and experience. Although all reviews attended regular training sessions at least once a year and had experiences as review physicians in KIAMI, the inter-observer variability still affects evaluations. Secondly, reviewers evaluated the exact same image according to both standards on the same day; thus, second evaluations may have been influenced. Thirdly, reviews already have prior understandings of the medical facilities performing the mammograms in about half the cases; although, they evaluated objectively, preconceptions on the type of facility could affect their clinical image evaluations.

In summary, the pass rate of clinical image evaluation of film mammograms according to the ACR standard was significantly lower than that of the Korean standard. Therefore, we suggest that tighter regulations, such as, raising the pass mark, subtracting more score for severe deficiencies, or regarding a very low score in even a single category as failure, are necessary to improve the mammography quality in Korea.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 3

Mammograms passed Korean standard but failed ACR standard. Average total scores according to Korean standards was 71, but these mammograms failed ACR standard due to score of 2 in exposure category. ACR = American College of Radiology

Fig. 4

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis shows optimal Korean standard pass mark of 77.0, when ACR standard was regarded as reference standard. ACR = American College of Radiology

References

1. Korean National Cancer Center. Report on the statistics for national cancer incidence 2006-2007. Korean National Cancer Center;2009.

2. Ko SS. Korean Breast Cancer Society. Chronological changing patterns of clinical characteristics of Korean breast cancer patients during 10 years (1996-2006) using nationwide breast cancer registration on-line program: biannual update. J Surg Oncol. 2008; 98:318–323.

3. Lee CH. Screening mammography: proven benefit, continued controversy. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002; 40:395–407.

4. Kim SH, Kim MH, Oh KK. Analysis and comparison of breast density according to age on mammogram between Korean and Western women. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2000; 42:1009–1014.

5. Bassett LW. The regulation of mammography. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1996; 17:415–423.

6. Suleiman OH, Spelic DC, McCrohan JL, Symonds GR, Houn F. Mammography in the 1990s: the United States and Canada. Radiology. 1999; 210:345–351.

7. Destouet JM, Bassett LW, Yaffe MJ, Butler PF, Wilcox PA. The ACR's Mammography Accreditation Program: ten years of experience since MQSA. J Am Coll Radiol. 2005; 2:585–594.

8. McLelland R, Hendrick RE, Zinninger MD, Wilcox PA. The American College of Radiology Mammography Accreditation Program. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991; 157:473–479.

9. Korean Society of Breast Imaging. A manual of the mammography quality control. Seoul: Sung Mun Gak;2001.

10. Korean Society of Radiology. Guidance on installation and management of special medical equipments. Accessed April 30, 2012. Available from: http://www.radiology.or.kr.

11. Bassett LW, Farria DM, Bansal S, Farquhar MA, Wilcox PA, Feig SA. Reasons for failure of a mammography unit at clinical image review in the American College of Radiology Mammography Accreditation Program. Radiology. 2000; 215:698–702.

12. Korean Institute for Accreditation of Medical Image. Accessed April 30, 2012. Available from: http://www.ikiami.or.kr/info/KMI418QD.aspx.

13. Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare. National health insurance system. Accessed April 30, 2012. Available from: http://english.mw.go.kr.

14. Li Y, Poulos A, McLean D, Rickard M. A review of methods of clinical image quality evaluation in mammography. Eur J Radiol. 2010; 74:e122–e131.

15. Lee SH, Choe YH, Chung SY, Kim MH, Kim EK, Oh KK, et al. Establishment of quality assessment standard for mammographic equipments: evaluation of phantom and clinical images. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2005; 53:117–127.

16. Moon WK, Kim TJ, Cha JH, Cho KS, Choi EW, Lee YJ, et al. Clinical image evaluation of mammograms: a national survey. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2003; 49:507–511.

17. National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation. Statistics of the diagnostic radiation generator devices installation in the last 5 years. 2010. Accessed April 30, 2012. Available from: http://www.nifds.go.kr.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download