Abstract

Chlorhexidine is widely used as an antiseptic and disinfectant in medical and non-medical environments. Although the sensitization rate seems to be low, its ubiquitous use raises the possibility of sensitization in many patients and medical care workers. We describe a patient with anaphylaxis during digital rectal examination with chlorhexidine jelly. Urticaria, angioedema, dyspnea, and hypotension developed within a few minutes of the rectal examination. The patient fully recovered after treatment with epinephrine and corticosteroids. Skin tests for chlorhexidine were undertaken 5 weeks later, showing positive prick and intradermal skin tests. Within 30 min of the skin test, the patient complained of febrile sensation, chest tightness, angioedema, and urticaria on the face and trunk. An enzyme allergosorbent test for latex was negative. We present this case to alert clinicians about hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine that could potentially be life-threatening. We suggest that chlorhexidine should be recognized as a causative agent of anaphylaxis during procedural interventions.

Chlorhexidine, a cationic bisguanide antiseptic and disinfectant, is active against a broad spectrum of bacteria, mycobacteria, some viruses, and some fungi. In a medical setting, it is used as an acetate or gluconate salt, and is commonly used with other antiseptics or local anesthetics. In addition, it is also used in non-medical products such as soaps, cosmetics, toothpaste, and mouthwash. These ubiquitous applications of chlorhexidine raise the possibility of sensitization in a large proportion of the general population (1).

Since the introduction of chlorhexidine, various hypersensitivity reactions to this agent have been reported, including contact dermatitis, photosensitive dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, contact urticaria, occupational asthma, and immediate hypersensitivity reactions such as severe anaphylactic shock (2), which is a rare but life-threatening complication. Recently, there has been an increased focus on hypersensitivity reactions due to chlorhexidine, owing to increased numbers of well-documented reports of chlorhexidine-induced anaphylactic shock (2, 3). In the following case report, we describe a case of anaphylaxis due to topical skin application of chlorhexidine during digital rectal examination.

A 54-yr-old man visited our hospital to assess lower urinary tract symptoms. The patient had been treated for diabetes mellitus and had undergone a hemorrhoidectomy 2 yr previously. His medical history was unremarkable except for an idiosyncrasy to radio-contrast dye, and he had no other atopic disease. The physical examination revealed nothing abnormal. A digital rectal examination was performed with 10 mL 0.05% chlorhexidine as the rectal local disinfectant by a doctor wearing latex gloves. Within 2 min of the examination, the patient complained of faintness and chest tightness. Generalized urticarial rash, facial swelling, and lip swelling subsequently developed. The patient's blood pressure decreased to 75/48 mmHg. He was transferred quickly to the emergency department, and received subcutaneous epinephrine (1:1,000, 0.3 mL), and intravenous chlorpheniramine 45 mg and methylprednisolone 60 mg. Fortunately, his blood pressure increased to a normal level soon after administration of epinephrine, and his skin lesions started to recover within several minutes. The patient was kept under observation for 5 hr and made a complete recovery.

Laboratory results included a: white blood cell count 12,000/m3 (eosinophils 0.7%), hemoglobin 15.3 g/dL, platelet count 261,000/µL, and total immunoglobulin E 17 kU/L (0-85 kU/L). A reaction to latex was suspected, but latex-specific IgE (Latex®, UniCAP, Phadia, Sweden) was not found.

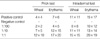

Five weeks later, a skin prick test to common allergens (Dermatophagoides farinae, D. pteronyssinus, molds, and pollens) was negative and a skin test with 5% chlorhexidine (Hexidine solution 5% green®, Green pharmaceutical company, Korea) was performed. A dilution of 1:100 chlorhexidine was weakly positive, however, both dilutions of 1:10 and 1:1 were strongly positive; In addition to skin prick testing, we also performed intradermal test with 5% chlorhexidine. Dilutions of 1:100, 1:10, and 1:1 all gave positive results (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Normal saline and ethylalcohol were used as negative controls, and histamine was used as a positive control. Thirty minutes after the chlorhexidine prick and intradermal tests, the patient complained of febrile sensation, chest tightness, facial swelling, and pruritic skin rash (Fig. 2). He recovered spontaneously several hours later.

Chlorhexidine (chemical formula C22H30Cl2N10-C6H12O7) is a widely used disinfectant in medical and non-medical settings. As an acetate or gluconate salt, chlorhexidine is topically applied to skin or mucous membranes, wounds, burns, surgical instruments, and surfaces.

There was only one case report on anaphylactic shock due to chlorhexidine in Korea. In 2007, Kim et al. reported a severe anaphylactic reaction after the use of chlorhexidine jelly for the urethral catheterization during anesthesia, presenting the positive skin test for chlorhexidine (4). We described a patient who suffered from life-threatening anaphylaxis during a digital rectal examination. Initially, the reaction was erroneously attributed to natural rubber latex. However, the test for latex-specific IgE was negative, leading to a suspicion of an alternative causative agent, such as chlorhexidine. Because skin prick test and intradermal test were positive for chlorhexidine, this case was the second report of chlorhexidine anaphylaxis confirmed by skin test. Owing to the high worldwide use of chlorhexidine, anaphylactic shock associated with this agent is likely to be under-reported. We would like to draw attention to the risks associated with the use of this antiseptic.

Today, there are an increasing number of reports of anaphylaxis due to chlorhexidine (1-8). A previous study reported specific IgE antibodies to chlorhexidine (9). There are several reports that patients with prior sensitization to chlorhexidine and with relatively mild contact dermatitis may be at increased risk of severe immediate-type reactions (10, 11).

Life-threatening reactions are generally associated with mucosal or parenteral exposure (11). Chlorhexidine may cause anaphylaxis by the mucosal route at a much lower concentration than elsewhere, generally as low as 0.05% (3, 6). As a result, it has previously been suggested that chlorhexidine should not be used on mucosal surfaces (11). A case of severe anaphylactic reaction during anesthesia associated with the use of chlorhexidine-impregnated central venous catheters was recently reported (12). Radioisotope studies have shown that chlorhexidine can penetrate unbroken skin. Both local and systemic symptoms have been described in this setting (13).

If an anaphylactic reaction is identified or suspected, basic resuscitative measures should be undertaken. However, it is also important that several diagnostic tests should be performed after recovery to identify the causative agent. The skin prick test is the main test used when hypersensitivity reaction is suspected. This should be performed by a suitably qualified doctor according to well-established criteria (14). It is recommended that, if possible, all potential causative agents are investigated. In patients who have experienced an unexplained allergic event during surgical or interventional procedures, chlorhexidine should be considered as a potential causative agent. Our report demonstrates that chlorhexidine can act as a sensitizer and that life-threatening anaphylactic shock can occur even if it is applied to the mucosa at the recommended concentration of 0.05%.

Application of chlorhexidine to the mucous membranes can cause severe anaphylactic reactions. Hypersensitivity to chlorhexidine is rare, but its potential to cause anaphylactic shock during hospital procedures is likely to be underestimated. We suggest that chlorhexidine should be used with caution and that it should routinely be considered as a causative agent in unexplained fatal reactions associated with medical procedures.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Skin prick (A) and intradermal test (B) with 5% chlorhexidine. A dilution of 1:100 chlorhexidine was weakly positive, and both dilution of 1:10 and 1:1 were strongly positive.

a, a', positive control (histamine); b, b', negative control (saline); c, c', chlorhexidine 1:100 dilution; d, d', chlorhexidine 1:10 dilution; e, e', chlorhexidine 1:1 dilution.

References

1. Ebo DG, Bridts CH, Stevens WJ. Anaphylaxis to an urethral lubricant: chlorhexidine as the "hidden" allergen. Acta Clin Belg. 2004. 59:358–360.

2. Torricelli R, Wuthrich B. Life threatening anaphylactic shock due to skin application of chlorhexidine. Clin Exp Allergy. 1996. 26:112.

3. Jayathillake A, Mason DF, Broome K. Allergy to chlorhexidine gluconate in urethral gel: report of four cases and review of the literature. Urology. 2003. 61:837.

4. Kim TH, Cho SJ, Kim HJ, Noh GJ. Chlorhexidine anaphylaxis after urethral catheterization during anesthesia: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2007. 52:104–106.

5. Krautheim AB, Jermann TH, Bircher AJ. Chlorhexidine anaphylaxis: case report and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 2004. 50:113–116.

6. Wicki J, Deluze C, Cirafici L, Desmeules J. Anaphylactic shock induced by intraurethral use of chlorhexidine. Allergy. 1999. 54:768–769.

7. Garvey LH, Roed-Petersen J, Husum B. Anaphylactic reactions in anaesthetized patients- four cases of chlorhexidine allergy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001. 45:1290–1294.

8. Thong BY, Yeow-Chan . Anaphylaxis during surgical and interventional procedures. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004. 92:619–628.

9. Layton GT, Stanworth DR, Amos HE. The incidence of IgE and IgG antibodies to chlorhexidine. Clin Exp Allergy. 1989. 19:307–314.

10. Ebo DG, Stevens WJ, Bridts CH, Matthieu L. Contact allergic dermatitis and life- threatening anaphylaxis to chlorhexidine. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998. 101:128–129.

11. Okano M, Nomura M, Hata S, Okada N, Sato K, Kitano Y, Tashiro M, Yoshimoto Y, Hama R, Aoki T. Anaphylactic symptoms due to chlorhexidine gluconate. Arch Dermatol. 1989. 125:50–52.

12. Stephens R, Mythen M, Kallis P, Davies DW, Egner W, Rickards A. Two episodes of life-threatening anaphylaxis in the same patient to a chlorhexidine-sulphadiazine-coated central venous catheter. Br J Anaesth. 2001. 87:306–308.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download