Introduction

Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries are rare and they have been discovered in 0.67% of the patients who undergo coronary arteriography and in 0.8% of patients at autopsy.1)2) Although rare, they can cause important coronary morbidity and mortality leading to angina, syncope, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction and sudden death.3)

Coronary artery fistula (CAF) is an abnormal communication between an epicardial coronary artery and the cardiac chambers, the major vessels (the vena cavae, sub-pulmonary veins and pulmonary artery) or other structures.4)5) Congenital CAFs joining into the pulmonary artery are rare cardiac anomalies. CAFs arising from two coronary arteries are even rarer, especially when they are combined with valvular heart disease.6-9) Furthermore, a few cases of coronary-pulmonary artery fistula combined with aortic regurgitation have been previously reported.6)9)

To the best of our knowledge, the present report may be the first Korean case of 55-year-old woman with severe aortic regurgitation and she also had bilateral coronary-pulmonary artery fistulas.

Case

A fifty-five year old female patient was admitted with a squeezing type chest pain of 5 days duration, and this symptom was not effort related. She did not have any atherosclerotic risk factors or any significant past medical history. There was no family history of aortic, collagen, vascular or congenital heart disease.

She had a regular pulse rate of 71 beats/min, a blood pressure of 140/30 mmHg and a respiratory rate 16 breaths/min.

On physical examination, cardiac auscultation revealed 4 to 6 grade diastolic murmurs at the aortic and pulmonary areas radiating to the upper back.

Her elecrocardiography demonstrated left ventricular hypertrophy by the voltage. No ST segment and T wave changes were apparent.

The blood chemistries, including the cardiac enzyme and lipid profiles, were within normal limits. On chest X-ray, cardiomegaly was noted (cardiothoracic ratio: 0.6). Both transthoracic echocardiography and transesophageal echocardiography relatively revealed a mildly dilated left ventricle and good regional wall motion with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 65%, but she had severe aortic regurgitation with incapacitated, minimally calcified cusps of the aortic valve (Fig. 1). The thallium 201 myocardial perfusion scintigraphy was normal.

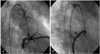

On coronary angiography, the bilateral CAFs arising from the first diagonal branch of the left anterior descending artery and the conal branch of the right coronary artery were detected. Both CAFs drained into the pulmonary artery (Fig. 2). There was no obstructive lesion in all of the coronary arteries and the spasm studies were negitive. On the aortogram, severe aortic regurgitation was detected and the shunt ratio (Qp/Qs) was 1.15 (Fig. 3).

Since aortic valve replacement was required in this case, we recommended CAF ligation during valvular surgery. Yet she wanted to be operated on in the other hospital, and she was then transferred. When we called her by the telephone, she was being treated with medical therapy in the other hospital.

Discussion

The embryogenesis of CAF is uncertain. There are six coronary enlargements in the embryo: three in the developing aorta and three in the developing pulmonary artery. These enlargements normally involute, except for the two from the right and left aortic sinuses. A coronary to pulmonary artery fistula may result from persistence of one or more of the pulmonary arterial enlargements, hence the term accessory coronary artery.10) The relatively high incidence of bilateral CAFs to the pulmonary artery is in accord with this theory.10) Our case also showed that the bilateral CAFs drained into the pulmonary artery, and the pulmonary-systemic flow ratio was 1.15.

CAFs are usually discovered by chance at coronary angiography. In addition, they can be diagnosed during the evaluation of a continuous murmur at the precordium, which is atypical for patent ductus arteriosus, myocardial ischemia and congestive heart failure, and this is rarely found during investigating the etiology of bacterial endocarditis.11)12) The most frequent complaints of patients with coronary artery fistula are angina pectoris, atypical chest pain and lethargy. The pathophysiologic mechanisms of the symptoms are volume overload as a result of the shunt, coronary steal that causes a decreased myocardial oxygen supply and the lack of capillary formation.12) However, small fistulas, and especially those that drain into the main pulmonary artery and the left ventricle, are usually benign. A pulmonary-systemic flow ratio exceeding 1.5 : 1 is recommended as a basic criterion for intervention, but aneurysmal degeneration, coronary rupture or side-branch obstruction may also necessitate surgery.13) In addition, the first manifestation may be sudden death due to myocardial infarction or rupture of its aneurysm or a coronary aneurysm. Moreover, endocarditis, intracardiac shunt and dyspnea can be observed.14)15)

CAFs can be associated with valvular heart disease.5-9) Several cases of coronary to pulmonary artery fistula combined with valvular heart disease, principally mitral stenosis, have been reported.6-8) CAFs combined with severe aortic regurgitation are relatively rare in adults.7)9) To the best of our knowledge, this is the first Korean case of an adult who had bilateral coronary-pulmonary artery fistulas associated with severe non-rheumatic aortic regurgitation. Although CAFs can cause myocardial ischemia by the mechanism of coronary steal, the coexistence of severe aortic regurgitation might augment the myocardial ischemia. Most of these cases that showed valvular heart disease with the coronary artery fistula were not treated with artificial valves, but the fistula was surgically occluded and the patients revealed a good prognosis.5-9) Therefore, if cardiac pathologies with the concomitant coronary artery fistula require surgical treatment, then we recommend the fistula be surgically occluded, as was done in our case with severe aortic regurgitation.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download