Abstract

Intraosseous arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in the craniofacial region is rare. When it occurs, it is predominantly located in the mandible and maxilla. We encountered a 43-year-old woman with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome affecting the right lower extremity who presented with a left orbital chemosis and proptosis mimicking the cavernous sinus dural arteriovenous fistula. Computed tomography angiography revealed an intraosseous AVM of the sphenoid bone. The patient's symptoms were completely relieved after embolization with Onyx. We report an extremely rare case of intraosseous AVM involving the sphenoid bone, associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome.

Intraosseous arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a rare form of extracranial AVM.5)6) The location most frequently involved is the craniofacial region, especially the mandible followed by the maxilla.2) Most lesions present as excessive, recurrent hemorrhage following dental eruption or surgical extraction.2) We encountered a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) who presented with insidious onset of ipsilateral retroorbital pain, conjunctival injection, proptosis, and diplopia mimicking cavernous sinus dural arteriovenous fistula (CSDAVF) and was found to have an intraosseous AVM involving the skull base.

A 43-year-old female was referred to our hospital under the impression of a left CSDAVF. On presentation, she revealed left chemosis and proptosis that had developed ten days previously following several weeks of ipsilateral retroorbital pain and headache. She also had diplopia mainly due to ipsilateral abducens palsy. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) from the referring hospital showed a dark-signaled void lesion at the left paracavernous region and mild dilatation of the ipsilateral cavernous sinus and superior ophthalmic vein.

On physical examination, her right lower leg was hypertrophied with a geographic pattern of bluish cutaneous stains (Fig. 1). No vascular bruit was audible in the limb and she had no complaints about her leg. There was no family history of note, including no history of vascular malformations. We diagnosed our patient as KTS basis on her features.8)

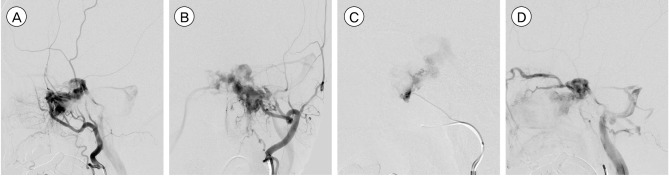

Angiography showed a triangular-shaped vascular chamber fed by multiple feeders of the left external carotid artery (ECA) especially from the terminal branches of the left internal maxillary artery and accessory meningeal artery (Fig. 2A, B, C). The vascular chamber drained via the ipsilateral cavernous sinus with significant reflux into the ipsilateral superior and inferior ophthalmic veins while the inferior petrosal sinus was patent (Fig. 2D). No additional feeder was noted on internal carotid injections and right external carotid angiography. A subsequent right femoral arteriogram showed no vascular abnormalities in her hypertrophied lower leg.

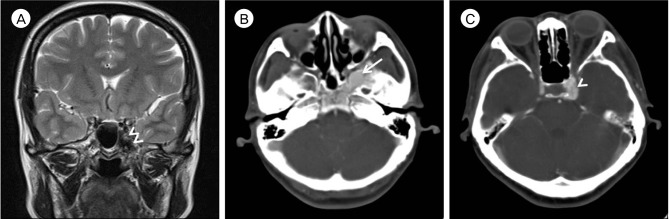

A retrospective review of her brain MRI showed that the vascular mass corresponded with the dark-signaled mass in the left side of the sphenoid body and the medial aspect of the greater wing (Fig. 3A). Subsequent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed an osteolytic space of densely enhancing vascular chamber surrounded by a sclerotic bony margin, consistent with imaging findings of an intraosseous AVM (Fig. 3B, C).

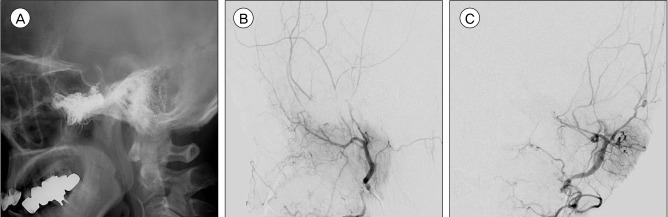

We performed endovascular treatment with Onyx (EV3, Irvine, CA, USA) embolization to relieve her orbital symptoms. The patient was placed under general anesthesia and was heparinized. Vascular access was obtained with a 5F guiding catheter (Envoy, Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA). On the super-selective angiograms of the major feeders, we found that the feeders near the vascular chamber consisted of numerous fine arteries rather than sizeable fistulas. The left accessory meningeal artery was catheterized with a dimethysulfoxide (DMSO)-compatible microcatheter (Rebar 14, EV3, Irvine, CA, USA), which was advanced to be sited in the prenidal position and successfully wedged. Following successful solidification of the reflux, the liquid embolic material (Onyx 18, EV3, Irvine, CA, USA) was injected slowly until it started to fill the draining vein. Three bottles of Oynx were injected. The post-embolization angiogram showed prominent reductions in vascularity and degree of AV shunting. The patient awakened from general anesthesia without any neurologic deficits. She was maintained on low-molecular-weight heparin during the postprocedural period. Her eye symptoms gradually resolved over 3 days and she was discharged without any complications. A 3-month follow-up angiogram demonstrated complete obliteration of the AVM (Fig. 4A, B, C).

Intraosseous AVM is very rare, with most reported lesions involving the head and neck region followed by the vertebra.2)5)6) Thus, our patient was especially interesting, because of not only the rarity of intraosseous AVM but the unusual clinical presentation with orbital symptoms. Most craniofacial AVMs reported to date presented with dental bleeding or other hemorrhage following trauma.2) To our knowledge, there has been no report of intraosseous head and neck AVM presenting with flow-related symptoms. Similar to a benign CSDAVF, this patient may have remained asymptomatic if the major route of venous drainage continued to be via the inferior petrosal sinus (IPS). Our patient became symptomatic due to retrograde reflux to the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins.

Angiographic diagnosis of intraosseous AVM in the skull base was difficult because the nidus was located on the left side sphenoid body and adjacent greater wing, not far from the usual osseous type of skull base DAVF.4)7) In contrast to a typical osseous DAVF, our patient's condition was characterized by a polygonal shaped venous chamber - not a network of fine vessels - within the bone as a large ectatic draining vein. We successfully reduced her orbital symptoms by reducing shunting flow after embolization of the venous chamber using Onyx. However, we do not know how the lesion will eventually resolve.

Considering our patient's limb abnormality, the rare form of intraosseous AVM in this patient may be related to KTS. KTS is characterized as a triad of a localized vascular nevus, congenital varicosities on the same body part, and hypertrophy of tissues on that body part. KTS is frequently associated with congenital vascular malformations.8) However, vascular anomalies of the head and neck region are rarely associated with KTS, and there have been no reports to date on this type of intraosseous AVM in patients with KTS.9) The associations between KTS and vascular abnormalities in the head and neck region, including intraosseous AVM, are not well understood. Numerous protein factors have been found to regulate vascular morphogenesis.10) The KTS susceptibility gene AGGF1 was identified through genetic studies on vascular morphogenesis, but there is no clear evidence so far that KTS is linked to any genetic aberration.1)10) Intraosseous AVM and KTS may be pathogenically similar, in that both are caused by errors in vascular morphogenesis. Future studies of genes involved in vascular anomalies may provide insights into their relationship.

The KTS patients are characterized as having, hypercoagulability, including higher rates of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and thromboembolic complications than non-KTS patients.3) Aggressive intra- and postprocedural DVT prophylaxis has been recommended for these patients, and low-molecular-weight heparin may be effective.9) Our patient was heparinized during the embolization procedure and administered low-molecular-weight heparin afterward. The patient experienced no thromboembolic events during the periprocedural period.

This report describes a very rare case of intraosseous AVM in the sphenoid bone associated with KTS. It was successfully treated with Onyx embolization. If an endovascular treatment is considered in KTS patients, it is important to know specific characteristics of this syndrome, including hypercoagulability, reducing any periprocedural thrombosis related morbidity.

References

1. Alomari AI, Orbach DB, Mulliken JB, Bisdorff A, Fishman SJ, Norbash A, et al. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and spinal arteriovenous malformations: An erroneous association. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010; 10. 31(9):1608–1612. PMID: 20651014.

2. Fan X, Qiu W, Zhang Z, Mao Q. Comparative study of clinical manifestation, plain-film radiography, and computed tomographic scan in arteriovenous malformations of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002; 10. 94(4):503–509. PMID: 12374928.

3. Jacob AG, Driscoll DJ, Shaughnessy WJ, Stanson AW, Clay RP, Gloviczki P. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: Spectrum and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998; 1. 73(1):28–36. PMID: 9443675.

4. Jung C, Kwon BJ, Kwon OK, Baik SK, Han MH, Kim JE, et al. Intraosseous cranial dural arteriovenous fistula treated with transvenous embolization. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009; 6. 30(6):1173–1177. PMID: 19246532.

5. Knych SA, Goldberg MJ, Wolfe HJ. Intraosseous arteriovenous malformation in a pediatric patient. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992; 3. (276):307–312. PMID: 1537171.

6. Louis RG Jr, Yen CP, Mohila CA, Mandell JW, Sheehan J. A rare intraosseous arteriovenous malformation of the spine. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011; 9. 15(3):336–339. PMID: 21663404.

7. Malik GM, Mahmood A, Mehta BA. Dural arteriovenous malformation of the skull base with intraosseous vascular nidus. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1994; 10. 81(4):620–623. PMID: 7931600.

8. Oduber CE, van der Horst CM, Hennekam RC. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: Diagnostic criteria and hypothesis on etiology. Ann Plast Surg. 2008; 2. 60(2):217–223. PMID: 18216519.

9. Star A, Fuller CE, Landas SK. Intracranial aneurysms in klippel-trenaunay/weber syndromes: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2010; 5. 66(5):E1027–E1028. discussion E1028. PMID: 20404675.

10. Timur AA, Driscoll DJ, Wang Q. Biomedicine and diseases: The Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, vascular anomalies and vascular morphogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005; 7. 62(13):1434–1447. PMID: 15905966.

Fig. 1

Photography shows the hypertrophy of our patient's right lower extremity, with bluish cutaneous stains.

Fig. 2

(A, B) Left external carotid angiogram shows the arteriovenous malformation (AVM) fed by the internal maxillary and accessory meningeal arteries. (C) Left accessory meningeal artery injection demonstrates a high flow AVM. (D) The nidus is drained via the ipsilateral cavernous sinus with significant reflux into the ipsilateral superior and inferior ophthalmic veins while the inferior petrosal sinus is patent.

Fig. 3

(A) Brain magnetic resonance image with T2-weighted coronal image shows that the vascular mass corresponded with the dark-signaled mass (Double arrowheads) in the left side of the sphenoid body and the medial aspect of the greater wing. (B, C) Contrast-enhanced brain computed tomography shows a vascular abnormality localized in the sphenoid bone near the left paracavernous region. The abnormal vascular lesion (Arrow) is mainly located in sphenoid bone. The draining vein (Arrowhead) is located in the paracavernous region.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download