Abstract

Background

The relationship between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) has been confirmed; however, no clear evidence for the effectiveness of H. pylori eradication on ITP exists thus far. The purpose of this study was to investigate platelet recovery in chronic ITP after H. pylori eradication.

Methods

A total of 25 patients (18 male, 7 female; the median age of 55 years) diagnosed with ITP, whose platelet counts were less than 100×103/µL, were enrolled. They were tested for H. pylori infection by the rapid urea test or urea breath test. All patients received triple therapy for 7 or 14 days to eradicate H. pylori infection.

Results

Of the 25 patients, 23 (92%) were diagnosed with H. pylori infection. Of all the ITP patients, 11 (44%) exhibited a complete response (CR) to H. pylori eradication therapy; 6 (24%), a partial response (PR); and 8 (32%) were nonresponsive (NR). Predictive factors of response after H. pylori eradication therapy were platelet counts at the initial response (27.3% responders among patients with platelet counts <100×103/µL vs 100% responders among patients with platelet counts ≥100×103/µL, P<0.001) and H. pylori infectivity (73.9% responders among the H. pylori positive patients vs 0% responders among the H. pylori negative patients, P=0.032).

Conclusion

This study confirmed the efficacy of H. pylori eradication in increasing the platelet count in ITP patients. Further studies with a larger number of patients are necessary to identify the crucial predictive factors responsible for platelet recovery in chronic ITP patients with the H. pylori infection.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium that colonizes the stomachs of over half the human population. H. pylori is the predominant agent of active chronic gastritis and gastric and duodenal ulcers. H. pylori is a cofactor in the development of both gastric adenocarcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Recently, H. pylori has been implicated in various autoimmune disorders, including pernicious anemia and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) [1, 2]. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in adult ITP patients is 22% in the North American Caucasian population, 29% in the white French population; furthermore, it is nearly 50% in Italy, greater than 70% in Japan, 90.6% in Colombia. In South Korean adults, the prevalence was 64.7% in 1998 and 59.9% in 2005 [2-7].

H. pylori infection is driven by urease, flagella, and adhesions. Virulence factors such as CagA and VacA play roles in colonization and infection. Other virulence factors are H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) and cell-wall lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [8-10]. The role of H. pylori in the development of ITP is not yet known. Many hypotheses have been proposed to address the mechanisms by which H. pylori causes ITP. Platelet-associated immunoglobulin G, CagA, LPS etc., have all been reported to play a role in platelet apoptosis [11, 12].

Until now, there have been many studies on the relationship between H. pylori infection and ITP. Some studies have reported increased the platelet counts subsequent to the eradication of infection [13-17], whereas others have failed to demonstrate the same beneficial effects [18-20].

In this retrospective study of patients with chronic ITP and H. pylori infection, we assessed the efficacy of H. pylori eradication in the restoration of platelet count and identified predictive factors associated with the therapeutic response.

The medical records of 25 adult chronic ITP patients, seen at Kosin University Gospel Hospital in Busan, South Korea, between June 1996 and November 2009, were retrospectively examined for the presence of gastric H. pylori infection. The diagnosis of ITP was made according to the criteria set by the American Society of Hematology (ASH) guidelines [21] based on thrombocytopenia (platelet count of less than 100×103/µL). Cases of thrombocytopenia caused by drugs, pseudothrombocytopenia, family history consistent with inherited thrombocytopenia, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and autoimmune disorders were excluded. Patients with hepatitis were included if they had normal liver function and the inactive virus. Two patients with lymphoma were included; one had complete response to lymphoma treatment at the time of participation and the other was simultaneously diagnosed with ITP and diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Patients were excluded if they had been treated for H. pylori within 2 years of recruitment or if they had been treated with an antibiotic or proton pump inhibitor within the previous 4 weeks.

All 25 patients were screened for H. pylori infection using a 13C-urea breath test (UBT), serum H. pylori antibody, or a rapid urease test (CLO test) by an endoscopic biopsy.

H. pylori infection was treated with standard eradication therapy: amoxicillin 1,000 mg twice daily, clarithromcin 500 mg twice daily, and a proton pump inhibitor 40 mg twice daily for 1 or 2 weeks.

Platelet counts were assessed when patients reached remission after H. pylori eradication therapy, and were again assessed long after the completion of eradication treatment. These platelet counts were compared with those taken at the baseline.

The clinical response to treatment was defined by the International Working Group on ITP [22]. Complete response (CR) was defined as a platelet count of at least 100×103/µL for more than 2 months with or without maintenance therapy. Partial response (PR) was defined as a platelet count of at least 30×103/µL and at least doubling the baseline count over a period of more than 2 months. No response (NR) was defined as a platelet count below 30×103/µL, or when the platelet count did not increase to more than 50% of the pretreatment level with or without maintenance therapy.

Data are expressed as the median (range) as appropriate. The following variables were analyzed to identify factors associated with the improvement in the platelet count after eradication therapy: age, sex, disease duration, H. pylori infectivity, duration of H. pylori eradication therapy, platelet count upon H. pylori eradication, platelet count at initial response, concomitant treatment with steroid, existence of peptic ulcer, hepatitis virus carrier, and survival. A chi-square or Fischer exact test was used for analysis of categorical data; the t test was used to compare groups in which the data involved continuous variables. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Duration of response after H. pylori eradication was graphed by the Kaplan-Meier method. All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS software version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

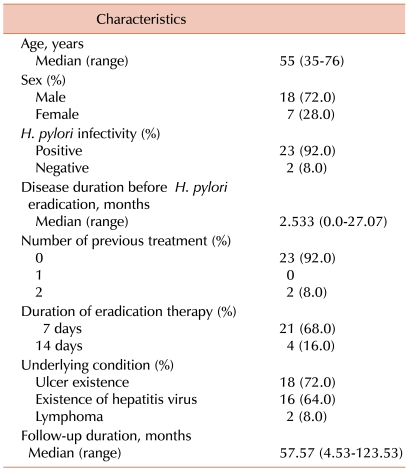

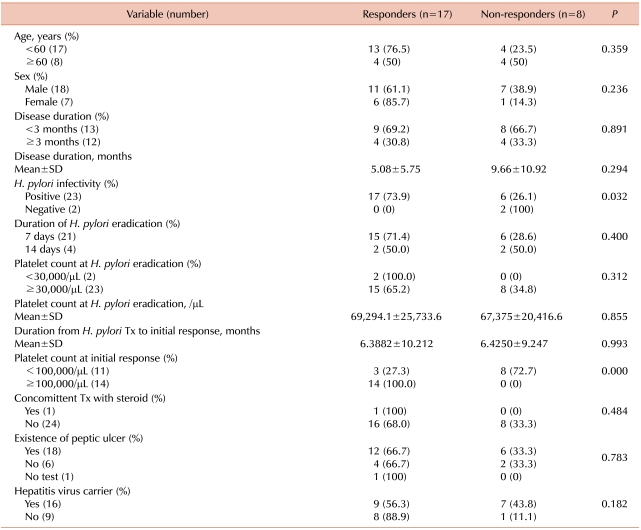

Background characteristics of the patients with ITP are indicated in Table 1. The median age was 55 years (range: 35-76 years), 18 were men (7 women), and the median platelet count was 78×103/µL (range: 6-96×103/µL). The median follow-up duration of this study was 57.57 months (range: 4.53-123.53 months). Twenty-three patients had histologically confirmed H. pylori infection from UBT or CLO test. All patients experienced complete bacterial eradication. Of these patients, 2 had received immunosuppressive and anti-RhD immunoglobulin treatment before H. pylori eradication therapy. Underlying conditions included peptic ulcer in 18 patients (72%), and 16 patients (64%) were carriers of hepatitis B or C, all with low viral titers, and who were not receiving treatment of hepatitis. Of the 2 patients with malignant lymphoma, 1 had achieved CR before the start of H. pylori eradication. The other patient was simultaneously diagnosed with ITP and lymphoma and experienced no platelet recovery after H. pylori eradication.

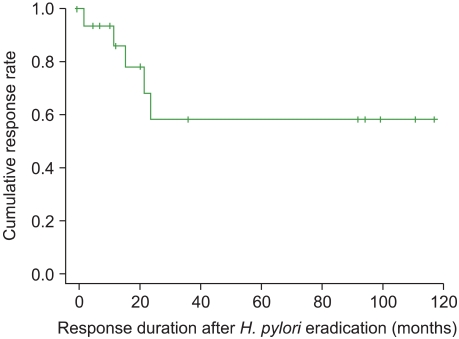

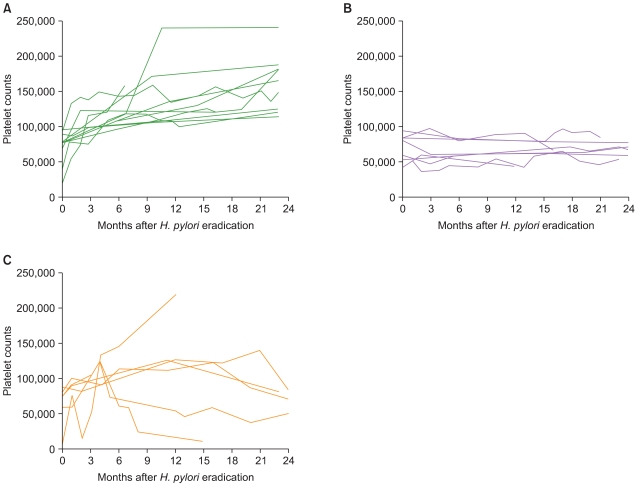

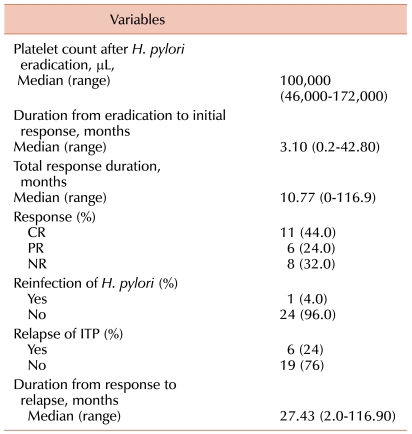

Outcomes after H. pylori eradication of the patients with ITP are indicated in Table 2. CR was obtained in 11 (44%) of the 25 patients, and a partial response in 6 (24%) patients, for an overall response rate (ORR) of 68%. Median follow-up duration was 57.57 months (range: 4.53-123.53 months) in this study. The median duration from eradication to initial response was 3.10 months (range: 0.2-42.8 months). H. pylori reinfection developed in 1 patient (4%) and ITP relapse developed in 6 patients (24%). The 1 H. pylori -reinfected patient also experienced an ITP relapse. The median duration from response to ITP relapse was 27.43 months (range: 2.0-116.9 months). The response duration in patients undergoing H. pylori eradication is shown in Fig. 1. Individual changes in platelet counts in responsive, non-responsive and relapsed patients with complete eradication are shown in Fig. 2.

Predictors of response to H. pylori eradication therapy included platelet counts at the initial response (27.3% responders among patients with platelet counts <100×103/µL vs 100% responders among patients with platelet counts ≥100×103/µL, P<0.001) and H. pylori infectivity (73.9% responders among the H. pylori positive patients vs 0% responders among the H. pylori negative patients, P=0.032) (Table 3). Other tested factors did not differ significantly between the responders and nonresponders. The response rates differed with age and hepatitis virus carrier status but these differences were not statistically significant (hepatitis virus carrier [56.3%] vs none hepatitis virus carrier [88.9%] and <60 years [76.5%] vs. ≥60 years [50.0%]). One patient experienced relapse 2 months after H. pylori eradication therapy, and the patient's platelet counts were restored by treatment with rituximab.

Many studies have shown an association between H. pylori infection and ITP, and substantial evidence has indicated that achieving H. pylori eradication can lead to a significant improvement in platelet counts in these H. pylori-positive ITP patients.

Gasbarrini et al. first reported that patients in whom H. pylori infection was eradicated showed significant increases in platelet count with the disappearance of anti-platelet antibodies [23]. Emilia et al. [16] reported that H. pylori eradicated ITP patients exhibited a significant increase in platelet count. Several studies on the H. pylori eradication therapy in Japan and Korea have documented similarly favorable results. Inaba, Sato, Kohda, Suzuki, and Song et al. demonstrated a favorable platelet response in patients in whom H. pylori was successfully eradicated [13-15, 17, 24]. The results of our study were comparable to those of previous studies and suggested the long-term efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapy in patients with H. pylori infection and ITP. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in the ITP patients in this study was 92%. A CR was obtained in 44%, with a PR obtained in 24%, for an ORR of 68%. These favorable results may be associated with more of our patients having baseline platelet counts of more than 30×103/µL and fewer patients having undergone prior treatment for ITP. We observed a median 27.43-months duration of response after H. pylori eradication (range: 2.0-116.9 months). In comparison with other studies, there were no remarkable differences in the median duration of responders ranging from 4 to 43.5 months [25].

In contrast to our study, an Italian report by Stasi et al. concluded that H. pylori eradication therapy had no favorable effect on patients with ITP [18]. Ahn and Suvajdzić et al. also described a poor response to H. pylori eradication therapy in patients with ITP in the United States and the United Kingdom, respectively [19, 20].

The platelet recovery rate after H. pylori eradication therapy appears to be as heterogeneous between studies as the response rates. In most studies, a shorter ITP duration is correlated with better chance of response [18, 26]. In one study, a complete response was associated with no prior prednisone therapy [27]. The presence of the HLA-DQB1*03 allele has also been associated with higher response rates [12]. There are conflicting reports about the predictive value of some characteristics such as age and baseline platelet count [13, 16, 17, 20]. Our study revealed that after H. pylori eradication both high platelet counts (more than 100×103/µL) at the initial response and the presence of H. pylori infection predicted better platelet recovery. However, no significant difference in the response rate with age or hepatitis virus carrier status was noted between the responders and non-responders. There have been some questions about the association between hepatitis C and autoimmune thrombocytopenia. Panzer et al. suggested that thrombocytopenia in patients with hepatitis C infection may be due to a variety of non-immune and immune mechanisms [28]. In our study, hepatitis carriers exhibited poorer platelet recovery rates than noncarriers, indicating that other mechanisms may be associated with the poor response rate in ITP patients who are hepatitis carriers. On the basis of a previous report that suggests lymphoma has the same mechanism of platelet destruction as primary ITP infection [29]. 2 patients with lymphoma were included in this study to determine whether their H. pylori infection possibly influenced a reduction of their platelet counts. One patient was responsive to the treatment whereas the other was not.

In conclusion, the eradication of H. pylori in ITP patients was effective in restoring platelet counts in patients at one institute in South Korea. A higher platelet count (>100×103/µL at initial response) and the presence of H. pylori infection were associated with platelet recovery after H. pylori eradication therapy. Further studies are required to clarify other causative factors involved in platelet recovery, monitor the duration of response, and understand the mechanism underlying the response to eradication therapy.

References

1. Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:1175–1186. PMID: 12374879.

2. Michel M, Cooper N, Jean C, Frissora C, Bussel JB. Does Helicobater pylori initiate or perpetuate immune thrombocytopenic purpura? Blood. 2004; 103:890–896. PMID: 12920031.

3. Russo A, Eboli M, Pizzetti P, et al. Determinants of Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence among Italian blood donors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999; 11:867–873. PMID: 10514119.

4. Graham DY, Kimura K, Shimoyama T, Takemoto T. Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: current status and future options. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994; 6(Suppl 1):S1–S4. PMID: 7735923.

5. Graham DY, Malaty HM, Evans DG, Evans DJ Jr, Klein PD, Adam E. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in an asymptomatic population in the United States. Effect of age, race, and socioeconomic status. Gastroenterology. 1991; 100:1495–1501. PMID: 2019355.

6. Michel M, Khellaf M, Desforges L, et al. Autoimmune thrombocytopenic Purpura and Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162:1033–1036. PMID: 11996614.

7. Yim JY, Kim N, Choi SH, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter. 2007; 12:333–340. PMID: 17669107.

8. Andersen LP. Colonization and infection by Helicobacter pylori in humans. Helicobacter. 2007; 12(Suppl 2):12–15. PMID: 17991171.

9. Amedei A, Cappon A, Codolo G, et al. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori promotes Th1 immune responses. J Clin Invest. 2006; 116:1092–1101. PMID: 16543949.

10. Taylor JM, Ziman ME, Huff JL, Moroski NM, Vajdy M, Solnick JV. Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide promotes a Th1 type immune response in immunized mice. Vaccine. 2006; 24:4987–4994. PMID: 16621176.

11. Stasi R, Provan D. Helicobacter pylori and Chronic ITP. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008; 206–211. PMID: 19074084.

12. Veneri D, De Matteis G, Solero P, et al. Analysis of B- and T-cell clonality and HLA class II alleles in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: correlation with Helicobacter pylori infection and response to eradication treatment. Platelets. 2005; 16:307–311. PMID: 16011982.

13. Inaba T, Mizuno M, Take S, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori increases platelet count in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in Japan. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005; 35:214–219. PMID: 15733077.

14. Sato R, Murakami K, Watanabe K, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on platelet recovery in patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164:1904–1907. PMID: 15451766.

15. Kohda K, Kuga T, Kogawa K, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on platelet recovery in Japanese patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and secondary autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol. 2002; 118:584–588. PMID: 12139750.

16. Emilia G, Luppi M, Zucchini P, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura: long-term results of bacterium eradication and association with bacterium virulence profiles. Blood. 2007; 110:3833–3841. PMID: 17652264.

17. Suzuki T, Matsushima M, Masui A, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura-a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005; 100:1265–1270. PMID: 15929755.

18. Stasi R, Rossi Z, Stipa E, Amadori S, Newland AC, Provan D. Helicobacter pylori eradication in the management of patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med. 2005; 118:414–419. PMID: 15808140.

19. Ahn ER, Tiede MP, Jy W, Bidot CJ, Fontana V, Ahn YS. Platelet activation in Helicobacter pylori-associated idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: eradication reduces platelet activation but seldom improves platelet counts. Acta Haematol. 2006; 116:19–24. PMID: 16809885.

20. Suvajdzić N, Stanković B, Artiko V, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication can induce platelet recovery in chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Platelets. 2006; 17:227–230. PMID: 16769600.

21. George JN, Woolf SH, Raskob GE, et al. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a practice guideline developed by explicit methods for the American Society of Hematology. Blood. 1996; 88:3–40. PMID: 8704187.

22. Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009; 113:2386–2393. PMID: 19005182.

23. Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F, Tartaglione R, Landolfi R, Pola P, Gasbarrini G. Regression of autoimmune thrombocytopenia after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1998; 352:878. PMID: 9742983.

24. Song MK, Chung JS, Shin HJ, Choi YJ, Cho GJ. Outcome of immunosuppressive therapy with Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Korean Med Sci. 2008; 23:445–451. PMID: 18583881.

25. Stasi R, Sarpatwari A, Segal JB, et al. Effects of eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review. Blood. 2009; 113:1231–1240. PMID: 18945961.

26. Fujimura K, Kuwana M, Kurata Y, et al. Is eradication therapy useful as the first line of treatment in Helicobacter pylori-positive idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura? Analysis of 207 eradicated chronic ITP cases in Japan. Int J Hematol. 2005; 81:162–168. PMID: 15765787.

27. Ando K, Shimamoto T, Tauchi T, et al. Can eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori really improve the thrombocytopenia in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura? Our experience and a literature review. Int J Hematol. 2003; 77:239–244. PMID: 12731666.

28. Panzer S, Seel E. Is there an increased frequency of autoimmune thrombocytopenia in hepatitis C infection? A review. Wien med Wochenschr. 2003; 153:417–420. PMID: 14648921.

29. Liebman HA. Recognizing and treating secondary immune thrombocytopenic purpura associated with lymphoproliferative disorders. Semin Hematol. 2009; 46(1 Suppl 2):S33–S36. PMID: 19245932.

Fig. 1

Response duration after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). The median duration from response to relapse of ITP was 27.43 months (range, 2.0-116.9 months).

Fig. 2

Individual changes of platelet counts in responsive, non-responsive and relapsed patients with complete Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication were shown. Time course of platelet counts after H. pylori eradication therapy in responsive patients (A), non-responsive patients (B), and relapsed patients (C). In Fig. 1(C), 1 patient relapsed at 2 months after H. pylori eradication therapy and then platelet counts recovered after treatment with rituximab.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download