Abstract

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a rare hereditary disorder characterized by formation of blisters following minor trauma. It has been traditionally categorized by the level of basement membrane zone separation into EB simplex (EBS), junctional EB (JEB), and dystrophic EB (DEB). Recently, hemidesmosomal EB has been proposed as a fourth category, which includes EB with muscular dystrophy and EB with pyloric atresia. We report here on a case of concomitant occurrence of EB and pyloric atresia, a rare form of EB.

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) comprises a group of genetically-mediated skin disorders associated with blister formation induced by trauma. According to the level of basement membrane disruption, EB has been divided into three major categories: EB simplex (EBS), junctional EB (JEB) and dystrophic EB (DEB)1. In addition, two more rare forms of EB, EB with pyloric atresia and EB with muscular dystrophy, have been more recently described as hemidesmosomal EB1. There are variable degrees of cutaneous involvements such as localized or widespread blistering depending on sub-type2-4. EB is diagnosed by immunofluorescence or electron microscopy.

Among the sub-types, EB with pyloric atresia is particularly rare form of EB5. Herein, we report a case of EB associated with congenital pyloric atresia and give a brief review of the relevant literature.

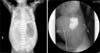

A female premature infant with a birth weight of 2,330 g was born at gestation week 33. On the second day after birth, general condition was much improved and oral nutritional supplements were started. After starting the oral supplements, however, the patient started vomiting and the abdomen became distended. Abdominal radiographs revealed free air in the abdomen. The patient was diagnosed with panperitonitis and underwent emergency surgery. During the operation, gastric perforation was observed and was completely repaired. Abdominal radiographs taken after the operation revealed a single bubble sign representing a distended stomach with no distal gases. Gastrografin was administered for the evaluation of the intestinal obstruction, and showed complete obstruction at the level of the pyloric channel (Fig. 1).

Blood chemistry revealed decreased levels of albumin (2.6 g/dl) and sodium (121 mmol/L), while level of C-reactive protein (35.37 mg/dl) was increased.

One day after the operation, multiple bullae and erosive patches were found. The lesions started at both ankles, which had been secured by plasters during the operation, and extended progressively to the entire body. The patient was referred to the department of dermatology with multiple bullae over the entire body. The patient had no family history of similar lesions. Physical examination revealed multiple variable sized vesicles and bullae over the entire body, but mainly on the extremities. Some lesions showed erosions and crusted patches (Fig. 2). A biopsy taken from a bulla on the lower legs showed separation between the epidermis and the dermis at the level of the dermoepidermal junction without inflammatory cell infiltrates. On electron microscopy, separation was observed in the lamina lucida (Fig. 3A, B). Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive reactions against plectin (Fig. 3C). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with EB with pylroric atresia, a type of hemidesmosomal EB.

A second operation was performed to correct the upper gastrointestinal obstruction. After the operation, the patient was treated with antibiotics (vancomycin and gentamycin) for control of post-operative inflammation and infection. She was also treated with regular skin cleanings, dressing with Vaseline®, antiseptics and topical antibiotics. In addition, electrolyte correction and nutritional supplements were given, and genetic studies were scheduled. However, she was discharged as requested by the parents, who wanted no further treatment.

EB is a rare genetic bullous disorder following minor trauma that is thought to be caused by mutations of proteins in the dermoepidermal junction and upper papillary dermis. Pyloric atresia is a rare congenital disease that causes partial or complete obliteration of the gastric outlet known to occur in less than 1% of gastrointestinal atresias6,7. Since the first report in 19688, some cases of EB with pyloric atresia have been reported. EB with pyloric atresia is an autosomal recessive trait. There is a structural defect of hemidesmosome due to altered expression of α6β4 integrin, which allows the epidermis to adhere to the underlying tissues at the dermoepidermal junction. The altered expression of α6β4 integrin is derived from homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations of genes ITGA6 and ITGB49. These defects can cause various degrees of bullous lesions over the whole body in newborns. In addition, vomiting and abdominal distension may occur due to a failure of lactation by intestinal obstruction. Intestinal obstruction may be the result of scar formation following recurrent damage of the pyloric mucosa10. Recurrent mucosal damage triggers mechanical or chemical irritations that lead to the adhesion of pyloric mucosal tissues10. EB with pyloric atresia may also have various urologic abnormalities, usually found after the neonatal period4. Most cases are severe and lethal in infancy because of the extensive extracutaneous epithelial damage and widespread blistering of the skin1.

In this case, there were multiple, variably-sized bullae characterized by progressive extension from the second day after birth. Intestinal obstruction was also found after the development of gastrointestinal symptoms including vomiting and abdominal distension. However, there was no ureterovesical obstruction in this case. Regular follow-up is needed to monitoring urinary symptoms because ureterovesical obstruction usually occurs after the neonatal period.

Even when intestinal obstructions are surgically corrected, the general prognosis of this disease is poor because of systemic manifestations such as electrolyte imbalance, failure to thrive, protein-losing enteropathy and septicemia. A review of 51 patients who underwent surgical procedures (among 73 patients with EB with pyloric atresia) reported an average survival time of only 70 days, despite surgical correction11. Some patients experienced a longer survival time of around 4 years, but these patients had extended cutaneous symptoms and extracutaneous complications affecting the urologic system and growth.

The diagnosis of EB is made by observation of characteristic clinical manifestations and histopathologic examinations. Electron microscope examination is essential for the diagnosis of EB because the exact level of tissue separation cannot be confirmed by light microscopy. EB with pyloric atresia can be diagnosed by the electron microscopic presence of blisters in the lamina lucida. Recently, genetic mutations have been discovered associated with each type of EB. Therefore, a genetic examination may be helpful for the diagnosis of EB and studies on prenatal diagnosis, genetic consultation and genetic treatment are now underway.

There are no definite treatment modalities in the treatment of EB with pyloric atresia. The treatments are mainly symptomatic including conservative managements such as appropriate dressing, infection control and nutritional supplements. Topical steroids may be used for the management of local inflammation. Despite surgical treatment of concomitant pyloric atresia, the prognosis of this disease is poor due to nutritional disturbance, absorption disturbance and progression of sepsis in many cases. Therefore, active surgical treatment tends to be withheld in patients with EB with pyloric atresia. However, a recent study reported that four of five patients presenting with stable vital signs tolerated treatment well after operation. Post-operatively, four patients were able to accomplish oral nutritional intake and maintain stable vital signs, while one patient died due to sepsis4. Unfortunately, oral nutritional intake after surgery was impossible at the time of discharge in this case. We diagnosed this case as an EB with pyloric atresia. There has been no report of EB with pyloric atresia in the Korean dermatologic literature. Dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of coincidence of vesicular lesions on the skin and pyloric atresia. Moreover, regular follow-up is needed because of the poor prognosis of this disease and the possibility of urologic complications such as ureterovesical obstruction.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Results of X-ray examination. There are no visible bowel gases on the abdominal X-ray except for a single large gastric bubble. In addition, an upper gastro-intestinal series with Gastrografin shows a 'single-bubble sign' representing the obstruction of the gastric outlet.

Fig. 2

Visual appearance of epidermolysis bullosa. Multiple, variably sized bullae, erosions, and crusted patches are scattered on the entire body but mainly on the extremities.

Fig. 3

Histopathologic, electron microscopy and immunohistochemical findings. (A) Histopathologic findings showing a separation between the epidermis and dermis at the level of the dermoepidermal junction (H&E, ×40, Inset: higher magnification view, H&E, ×100). (B) An electron micrograph showing the separation (*) in the lamina lucida. (C) Positive reaction of an immunohistochemical stain for plectin (×400).

References

1. Marinkovich MP, Bauer EA. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Epidermolysis bullosa. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 2008. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;505–516.

2. Sahebpor AA, Ghafari V, Shokohi L. Pyloric atresia associated with epidermolysis bullosa. Indian Pediatr. 2008. 45:849–851.

3. Wallerstein R, Klein ML, Genieser N, Pulkkinen L, Uitto J. Epidermolysis bullosa, pyloric atresia, and obstructive uropathy: a report of two case reports with molecular correlation and clinical management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000. 17:286–289.

4. Lestringant GG, Akel SR, Qayed KI. The pyloric atresia-junctional epidermolysis bullosa syndrome. Report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1992. 128:1083–1086.

5. Samad L, Siddiqui EF, Arain MA, Atif M, Parkash J, Ahmed S, et al. Pyloric atresia associated with epidermolysis bullosa-three cases presenting in three months. J Pediatr Surg. 2004. 39:1267–1269.

6. Al-Salem AH. Pyloric atresia associated with duodenal and jejunal atresia and duplication. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999. 15:512–514.

7. Okoye BO, Parikh DH, Buick RG, Lander AD. Pyloric atresia: five new cases, a new association, and a review of the literature with guidelines. J Pediatr Surg. 2000. 35:1242–1245.

8. Swinburne L, Kohler HG. Symmetrical congenital skin defects in siblings, abstracted. Arch Dis Child. 1968. 43:499.

9. Brown TA, Gil SG, Sybert VP, Lestringant GG, Tadini G, Caputo R, et al. Defective integrin alpha 6 beta 4 expression in the skin of patients with junctional epidermolysis bullosa and pyloric atresia. J Invest Dermatol. 1996. 107:384–391.

10. Butler DF, Berger TG, James WD, Smith TL, Stanely JR, Rodman OG. Bart's syndrome: microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunofluorescent mapping features. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986. 3:113–118.

11. Dank JP, Kim S, Parisi MA, Brown T, Smith LT, Waldhausen J, et al. Outcome after surgical repair of junctional epidermolysis bullosa-pyloric atresia syndrome: a report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1999. 135:1243–1247.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download