Abstract

Clonorchis sinensis is one of the most common causes of trematodiasis that is caused by the ingestion of raw fish contaminated with infective cysts. The adult flukes are predominantly present in the intrahepatic bile ducts, but occasionally they may be found in the pancreatic duct and extrahepatic bile ducts. The clinical manifestations depend on the number of flukes, the period of infestation, and complications such as pericholangitic abscess, cholangitis, bile duct stones, and cholangiocarcinoma. However, primary acute cholecystitis associated with C. sinensis infection is extremely rare. Herein, we report on a case of primary acute cholecystitis associated with C. sinensis infection.

Clonorchis sinensis causes an important foodborne parasitic infection that predominantly occurs as a hepatobiliary disease caused by the ingestion of a raw fish contaminated with infective cysts [1].

On the ingestion of raw fish, encysted parasites are released owing to the action of gastric juice and digestion of the cyst wall by trypsin in the duodenum, and the parasites develop into mature worms. The adult flukes are predominantly present in the intrahepatic bile ducts, but occasionally they may be present in the pancreatic duct and extrahepatic bile ducts.

Hepatobiliary complications of C. sinensis infection include cholelithiasis, pyogenic cholangitis, biliary obstruction, and cholangiocarcinoma secondary to mechanical injury to the biliary epithelium by the suckers of the worm and prolonged inflammation [2,3,4].

However, primary acute cholecystitis associated with C. sinensis infection is extremely rare [5]. Herein, we report on a case of primary acute cholecystitis associated with C. sinensis infection.

A 68-year-old man was admitted to the Emergency Department with a 2-day history of right upper quadrant pain and fever. This patient was resident in a town located near a river and reported a history of occasional ingestion of raw fish.

His past medical history indicated that the patient had undergone radical subtotal gastrectomy and Billroth-II anastomosis because of gastric cancer 10 years ago and inguinal herniorrhaphy two years ago.

The patient exhibited a blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg, a pulse rate of 84 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and a body temperature of 37.8℃. Physical examination indicated that he was acutely ill appearance without icteric sclera; we also noted tenderness in the right upper abdominal quadrant.

Routine hematological and biochemical investigations revealed leukocytosis and abnormal liver function test results: White blood cell, 12,400/mm3 (89% neutrophils); AST, 64 U/L; ALT, 94 U/L; total bilirubin, 2.8 U/L; and direct bilirubin, 1.4 U/L.

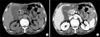

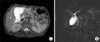

Abdominal CT showed a distended gallbladder, wall thickening, and pericholecystic fluid collection with mild dilatation of the extrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 1). MR cholangiography showed a distended gallbladder, pericholecystic fluid collection, and mild extrahepatic bile duct dilation without obstructive lesion (Fig. 2).

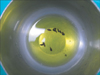

This patient had undergone laparotomy for possible peritonitis and a previous gastrectomy. During surgery, we observed not only turbid bile and necrotized gallbladder without gallstones, but also several flukes in the gall bladder and cystic duct (Fig. 3). On operative cholangiography to investigate the common bile duct (CBD), we did not observe bile duct dilatation or obstructive lesions (Fig. 4).

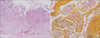

Pathologic examination of the gallbladder showed severe inflammatory mucosal changes and parasite ova, which was confirmed by the presence of C. sinensis (Fig. 5). The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged following the administration of praziquantel.

A recent survey revealed that clonorchiasis, a disease caused by infection with the trematode C. sinensis, remains highly prevalent, particularly in the riverside areas of Korea [6].

Hepatobiliary complications of C. sinensis infection include cholelithiasis, pyogenic cholangitis, biliary obstruction, and cholangiocarcinoma, secondary to mechanical injury to the biliary epithelium by the suckers of the worm and prolonged inflammation. Most patients with complications resulting from C. sinensis infection present with cholangitis due to biliary obstruction by the adult worms or stones [2,3,4]. Although primary acute cholecystitis associated with C. sinensis infection is extremely rare, the frequent ingestion of raw fish over a long period of time in endemic areas may lead to the requirement that C. sinensis related acute cholecystitis be included in the differential diagnosis of suspected cases of clonorchiasis.

In this case study, MR cholangiography revealed mild extrahepatic bile duct dilation, which suggests a history of radical subtotal gastrectomy rather than C. sinensis infection. Furthermore, we observed many flukes in the gallbladder and cystic duct during the surgery, which were not identified by MR cholangiography most likely owing to the flat morphology of the organism and due to its scattered distribution.

Radiological examinations are essential in the diagnosis of biliary tree diseases such as clonorchiasis. Clonorchiasis is primarily detected by screening sonography of the liver according to its pathognomonic findings of diffuse dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts, periductal echogenicity, and floating materials in the gallbladder. Periductal enhancement on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT or MR imaging may be a specific finding of active clonorchiasis [7,8].

Diffuse dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts up to the peripheral margin of the liver is observed, but larger intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts are usually not dilated or minimally dilated. These findings reflect the pathophysiology of bile ducts in C. sinensis. Adult C. sinensis worms usually reside in the medium-sized or small intrahepatic bile ducts. They are rarely found in the extrahepatic bile ducts except in cases of heavy infection. The histopathological changes to the bile ducts due to C. sinensis infection present as mucosal hyperplasia and periductal fibrosis with persistent ductal dilation [7]. We think that the possible pathogenesis of cholecystitis associated with C. sinensis infection might be an allergic reaction to the metabolites released from the adult worm in the CBD and gallbladder.

The relationship between cholelithiasis and C. sinensis infection is controversial. Qiao et al. [2] reported that C. sinensis eggs were detected in gallbladder stones, which suggests an association between C. sinensis infection and gallbladder stone formation, especially pigmented stones. Howerver, Choi et al. [9] reported that any evidence regarding C. sinensis was not related to an increased risk of either gallbladder or extrahepatic stones, but that it is significantly associated with the formation of intrahepatic stones.

In this case, we did not detect any gallstones, and whether C. sinensis infection is the etiological factor for cholecystolithiasis remains unclear.

We report on a rare case of primary acute cholecystitis associated with C. sinensis infection. This finding may provide incentive to initiate further studies of the pathogenesis of clonorchiasis-associated cholecystitis in prevalent areas.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Axial unenhanced (A) and contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography images (B) show a distended gallbladder with wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid collection. It also shows minimal dilatation of the peripheral intrahepatic bile ducts.

References

1. Hong ST, Fang Y. Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis, an update. Parasitol Int. 2012; 61:17–24.

2. Qiao T, Ma RH, Luo XB, Luo ZL, Zheng PM. Cholecystolithiasis is associated with Clonorchis sinensis infection. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e42471.

3. Stunell H, Buckley O, Geoghegan T, Torreggiani WC. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis due to chronic infestation with Clonorchis sinensis (2006: 8b). Eur Radiol. 2006; 16:2612–2614.

4. Shin HR, Oh JK, Masuyer E, Curado MP, Bouvard V, Fang YY, et al. Epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma: an update focusing on risk factors. Cancer Sci. 2010; 101:579–585.

5. Lai CH, Chin C, Chung HC, Liu H, Hwang JC, Lin HH. Clonorchiasis-associated perforated eosinophilic cholecystitis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007; 76:396–398.

6. Kim EM, Kim JL, Choi SY, Kim JW, Kim S, Choi MH, et al. Infection status of freshwater fish with metacercariae of Clonorchis sinensis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2008; 46:247–251.

7. Choi D, Hong ST. Imaging diagnosis of clonorchiasis. Korean J Parasitol. 2007; 45:77–85.

8. Kim GH, Kang DH, Kim TO, Song GA, Heo J, Cho M, et al. MRCP and ERCP findings in clonorchiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 64:439–440.

9. Choi D, Lim JH, Lee KT, Lee JK, Choi SH, Heo JS, et al. Gallstones and Clonorchis sinensis infection: a hospital-based case-control study in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008; 23(8 Pt 2):e399–e404.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download