Abstract

Purpose

There are scanty epidemiologic data on the prevalence of food allergy (FA) among preschool children in Asia. We performed this study to determine the prevalence and causative foods of immediate-type FA in early childhood in Korea.

Methods

A questionnaire-based, cross-sectional study was performed between September and October 2011. Children aged 0-6 years were recruited from 301 public child care centers in Seoul. Parents were asked to complete a questionnaire on FA. Children with FA were classified into "perceived FA, ever," "immediate-type FA, ever," and "immediate-type FA, current" according to the algorithm.

Results

A total of 16,749 children were included in this study. The prevalence of "perceived FA, ever," "immediate-type FA, ever," and "immediate-type FA, current" was 15.1%, 7.0%, and 3.7%, respectively. "Immediate-type FA, current" was reported by 182 (4.9%) out of 3,738 children aged ≤2 years, 262 (3.4%) of 7,648 children aged 3-4 years, and 177 (3.3%) of 5,363 children aged 5-6 years. Hen's egg (126/621) was the most frequent cause as the individual food item, followed by cow's milk (82/621) and peanut (58/621). Among the food groups, fruits (114/621), tree nuts (90/621) and crustaceans (85/621) were the most common offending foods. The three leading causes of food-induced anaphylaxis were hen's egg (22/47), cow's milk (15/47), and peanut (14/47).

Food allergy (FA) is an adverse immunologic response on exposure to food proteins.1 It affects all ages and symptoms can range from minor reactions to life-threatening anaphylaxis.1 Because the only treatment is avoidance of the offending foods, it is important for physicians to identify the prevalence of FA and common allergens for correct diagnosis and management.

A meta-analysis which assessed the prevalence of FA according to the method of assessment reported a 12% overall prevalence of FA in children between 0-16 years of age based on self-reporting questionnaire survey, and 3% in all ages on the basis of reports including a double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge.2 A study from Thailand reported a questionnaire-estimated prevalence of current FA of 9.3%. However, this rate dropped to 1.1% after oral food challenge tests among children aged 3-7 years.3 The self-reported prevalence of FA in a study conducted in Taiwan was 3.4% in children under 3 years of age and 7.7% in children aged 4-18 years.4 Several recent studies have also provided the prevalence of FA in Korean children. Prevalence of "perceived FA, current" which was assessed by questionnaire in a population-based, cross-sectional study was 3.3% in children aged 6-7 years and 4.5% in children aged 12-13 years.5 A birth cohort study reported a prevalence rate of immediate-type FA of 5.3% during the first year of life.6 However, there is relatively little information available regarding FAs in preschool-aged children in Korea.

Cow's milk, eggs, peanuts, wheat, and soy have been regarded as common causes of FA in childhood, while peanuts, tree nuts, fruit, and seafood are more frequent in adulthood in some reports of North America and Australia.7,8 In Korea, the leading causes of FA have been reported as eggs, milk, and peanut/nuts in infants, while eggs, crustaceans, and fruit were most common causative foods in school children.5,6 These results suggest that common food allergens are different according to the age during childhood.

Until now, studies concerning the prevalence of FA and common food allergens in Korea have been done in infants and school children. However, information on preschool children is not available. In particular, this age group in Korea tends to spend much more time in day care centers and so is at higher risk of serious events by accidental ingestion. The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence and causative foods of immediate-type FA and evaluate the difference according to age in early childhood.

A questionnaire-based, cross-sectional study was performed in Seoul, Korea, between September and October 2011. Children aged 0-6 years were recruited from 301 public child care centers. Parents of all children in the child care centers were given a detailed questionnaire to be completed. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Samsung Medical Center (SMC 2012-09-001) and informed consent was obtained from all parents.

The questionnaire included information regarding sex, age, birth date, and demographic data. If a child had ever had allergic reactions to foods, parents were asked to complete a more detailed questionnaire on the offending foods, time of onset after eating foods, repeated episodes of symptoms, symptoms and past medical history of physician-diagnosed FA. To identify the causative foods, multiple choice questions were given to parents or guardians. Questions regarding causative foods pertained to individual food items (hen's egg, milk, soy, peanut, wheat, buckwheat, and sesame) and food groups (tree nuts, fruits, vegetables, fishes, crustaceans, and meats). The questionnaire also contained whether the causative foods had been excluded from the diet.

FAs were defined as follows, according to the algorithm in Fig. 1. Briefly, a child was regarded to have "perceived FA, ever," if the parents answered "yes" to the question "Has your child ever had allergic reactions to food?" "Immediate-type FA, ever" was determined as having reproducible symptoms within 4 h after ingestion of foods. "Immediate-type FA, current" was considered when a child had maintained restriction of the suspected food. In addition, "physician-diagnosed FA, ever" was defined as a positive answer to physician-diagnosis with allergy tests in hospital settings among children with "perceived FA, ever."

We classified the reported symptoms according to the affected organs: 1) reactions on skin, mucosal tissue or both, such as an urticaria, rash, itching, redness, and angioedema; 2) gastrointestinal symptoms if the reactions involved vomiting, nausea, abdominal pain, or diarrhea; and 3) respiratory symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, and wheezing.9 Anaphylaxis was defined as symptoms that developed rapidly after exposure and affected at least 2 major organs.9 A telephone interview was conducted with parents who reported anaphylaxis to obtain more detailed information.

Data were analyzed using the SPSS 20.0 statistical software for Windows. The Chi-squared test was applied to determine the differences in the proportions. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were applied to examine the association between the prevalence of "immediate-type FA, current" and categorical variables. These included the gender, the age group, the season of birth, and the residential areas. A P value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

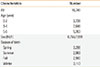

Data were collected from 16,982 children and 233 children were excluded because of incomplete questionnaire responses. A total of 16,749 children (8,758 boys and 7,991 girls) with a mean age of 3.7 years (range 0-6 years) participated in the survey. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the children for whom questionnaires were completed.

The prevalence of "perceived FA, ever," "immediate-type FA, ever," and "immediate-type FA, current" was 15.1%, 7.0%, and 3.7%, respectively (Table 2). In addition, 27.4% out of children who reported to have "perceived FA, ever" had been visited hospitals and underwent allergy tests, and 13.5% out of children with "perceived FA, ever" had been diagnosed as FA by a physician. Only 2.0% (342/16,749) of all subjects reported "physician-diagnosed FA, ever." "Immediate-type FA, current" was reported by 182 (4.9%) of 3,738 children aged 0-2 years, 262 (3.4%) of 7,648 children aged 3-4 years, and 177 (3.3%) of 5,363 children aged 5-6 years. Children aged 0-2 years displayed higher prevalence of FA than other age groups in univariate and multivariate analyses P<0.001). No difference was found in FA prevalence according to gender, residential area and season of birth in univariate and multivariate analyses.

Of the 621 children who responded to have "immediate-type FA, current," hen's egg (126/621) was the most frequent cause as the individual food item in children aged 0-6 years, followed by cow's milk (82/621), peanut (58/621) and soybean (17/621). Among the food groups, fruits (114/621), tree nuts (90/621) and crustaceans (85/621) were the most common offending foods causing allergy (Fig. 2). Of the children for whom "immediate-type FA, current" was reported, 148 (23.8%) showed symptoms to two or more foods. Overall, 584 (94.2%) children demonstrated skin or mucosal symptoms, followed by gastrointestinal symptoms (10.0%), anaphylaxis (7.6%), and respiratory symptoms (6.4%) (Table 3). Out of children with "immediate-type FA, ever," 55 (4.7%) children reported experiencing anaphylaxis at least once. Eventually, 47 (0.3%) children out of all subjects had a restricted diet due to anaphylaxis, after exclusion of eight children who outgrew their symptoms. All of eight children had urticarial and GI symptoms like vomiting and diarrhea and causes of anaphylaxis were milk (1), vegetable (carrot, 1), fruit (apple, 1), sesame (1), fish (1) and crustacean (3). The three leading causes of anaphylaxis were hen's egg (22/47), cow's milk (15/47), and peanut (14/47) (Fig. 3).

The self-reported prevalence of "immediate-type FA, ever" and "immediate-type FA, current" was 7.0% and 3.7%, respectively, showing that FA can be outgrown over time. Among the current immediate-type FA, the leading causative foods were milk (individual food), peanut (individual food), fruits (food group), tree nuts (food group) and crustaceans (food group).

Many studies regarding the prevalence of FA have been conducted in Western countries, but there are scanty epidemiologic data among preschool children in Asia. This is the largest epidemiologic study to evaluate the prevalence of immediate-type FA in preschool-aged children in Korea. The prevalence of FA in the present study was lower compared with 11.5% in Hong Kong Chinese children aged 2-7 years, 12.6% in Japanese children less than 6-years-of-age, and 10.1% in Colombia children aged 1-8 years.10-12 The differences may be due to not only the environmental factors including food consumption but also the structure of the questionnaire, which queried current dietary restrictions, and the repeatability and time lag of symptoms after eating the causative foods. Previous studies in Western countries that utilized serum specific IgE or food challenge tests reported lower rates of 1.2%-4.2%.13,14 Because the oral food challenge test is time-consuming and burdensome in the setting of a large study, we did not perform this test but tried to evaluate true immediate-type FA with questionnaires based on a logical algorithm. A prevalence rate of current FA of 3.3% has been reported in children aged 0-6 years in Korea.15 However, the study population was small (n=919) and the authors defined current FA as having allergic symptoms within the last 12 months and a physician diagnosis of FA, leading to underestimation or overestimation. In the present study, the prevalence of "physician-diagnosed FA, ever" was 2.0% of all children, and was much lower than 7.1% of "immediate-type FA, ever." Moreover, only about a quarter (26.6%) of children who experienced FA symptoms and 60% of children with anaphylaxis visited hospitals and underwent diagnostic tests. These results demonstrate the high prevalence of misunderstanding on the part of the guardians. Correct diagnosis and proper management in children with FA are important responsibilities of guardians; it is apparent from this study that more education is needed in this regard. These findings should be reflected in public policy that encourages guardians to consult medical professionals and to be provided with practical information, because misunderstanding of FA can result in unnecessary diet restriction, nutritional problems, or accidental exposure to offending foods.16

While hen's eggs and milk are universal food allergens worldwide, the order of other common food allergens varies in different countries, reflecting genetic factors, dietary habits, and exposure to allergenic foods early in life.17,18 For example, allergic reactions to peanut and/or tree nuts are common in Western populations, but the prevalence of peanut and/or tree nuts allergy is relatively low in Asian countries.19-22 Our study demonstrated the higher prevalence of peanut and/or tree nuts allergy compared to those in previous Korean studies, suggesting that more Korean children have been exposed to peanut and/or tree nuts frequently than previous years.6,15 In addition, fruits are one of the most common offending foods, which is consistent with our previous data in infants and school children.5,6 The results indicate that fruits were important food allergens from early childhood in Korea, unlikely other countries.14,23 Fruit allergies are a result of genuine reactivity to stable allergens through the gastrointestinal tract or the result of cross-reactivity to homologous pollen or latex-related allergens.24 Allergic reactions to fruits in our study could also have been a consequence of primary or secondary FA, because aeroallergen sensitization is reported to be common in young children.25 One possible explanation for the high prevalence of allergies to fruits and seafood is that they are commonly included in a weaning food in infancy. However, additional studies are needed to investigate the difference between our results and other reports.

Skin and/or mucosal symptoms were the most frequent reactions, similar to previous studies that reported skin reactions in more than 80% of cases.12,17 Anaphylaxis was reported in 0.3% out of all participants, which corresponds to the rate of 0.2%-0.4% among similar age groups in other countries.3,12 However, it is difficult to compare causative foods of anaphylaxis in our results with those in other studies, because of the lack of epidemiological data in this age group and very low frequency of anaphylaxis.

The present study did not reveal any factors associated with FA, although previous studies have suggested risk factors for the development of FA such as a family history of atopic disease, birth season, and the early ingestion of allergenic foods.6,26,27 However, this study had a limitation in assessing risk factors of FA, because our survey did not include questions on aspects including family history, which is known to be related to atopic diseases. In addition, tree nuts, fruits, vegetables, fishes, crustaceans, and meats were classified into food groups, in contrast to individual food items, and this categorization could make it difficult to compare the prevalence of allergy to food groups and single foods. Despite these limitations, our results provide useful information regarding FA in early childhood.

In conclusion, the estimated prevalence of current immediate-type FA was 3.7%, and was higher in younger children. The most common food allergens differed with age. These findings could help physicians to make a correct diagnosis and public health officials to plan targeted programs for FA.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristics | Number |

|---|---|

| All | 16,749 |

| Age (year) | |

| 0-2 | 3,738 |

| 3-4 | 7,648 |

| 5-6 | 5,363 |

| Sex (M/F) | 8,758/7,991 |

| Season of birth | |

| Spring | 3,298 |

| Summer | 2,983 |

| Fall | 2,980 |

| Winter | 3,113 |

Table 2

Prevalence of parent-reported food allergy

Table 3

Frequency of symptoms in children with "immediate-type food allergy, current"

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Seoul Association of Public Child Care Centers for their invaluable assistance. This study was supported by "the Korean Ministry of Environment" and "Food Promotion Fund in Seoul."

References

1. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125:S116–S125.

2. Rona RJ, Keil T, Summers C, Gislason D, Zuidmeer L, Sodergren E, Sigurdardottir ST, Lindner T, Goldhahn K, Dahlstrom J, McBride D, Madsen C. The prevalence of food allergy: a meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 120:638–646.

3. Lao-araya M, Trakultivakorn M. Prevalence of food allergy among preschool children in northern Thailand. Pediatr Int. 2012; 54:238–243.

4. Wu TC, Tsai TC, Huang CF, Chang FY, Lin CC, Huang IF, Chu CH, Lau BH, Wu L, Peng HJ, Tang RB. Prevalence of food allergy in Taiwan: a questionnaire-based survey. Intern Med J. 2012; 42:1310–1315.

5. Ahn K, Kim J, Hahm MI, Lee SY, Kim WK, Chae Y, Park YM, Han MY, Lee KJ, Kim JK, Yang ES, Kwon HJ. Prevalence of immediate-type food allergy in Korean schoolchildren: a population-based study. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012; 33:481–487.

6. Kim J, Chang E, Han Y, Ahn K, Lee SI. The incidence and risk factors of immediate type food allergy during the first year of life in Korean infants: a birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011; 22:715–719.

7. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. 9. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 117:S470–S475.

8. Yun J, Katelaris CH. Food allergy in adolescents and adults. Intern Med J. 2009; 39:475–478.

9. Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, Adkinson NF Jr, Bock SA, Branum A, Brown SG, Camargo CA Jr, Cydulka R, Galli SJ, Gidudu J, Gruchalla RS, Harlor AD Jr, Hepner DL, Lewis LM, Lieberman PL, Metcalfe DD, O'Connor R, Muraro A, Rudman A, Schmitt C, Scherrer D, Simons FE, Thomas S, Wood JP, Decker WW. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report--second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. Ann Emerg Med. 2006; 47:373–380.

10. Leung TF, Yung E, Wong YS, Lam CW, Wong GW. Parent-reported adverse food reactions in Hong Kong Chinese pre-schoolers: epidemiology, clinical spectrum and risk factors. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009; 20:339–346.

11. Iikura Y, Imai Y, Imai T, Akasawa A, Fujita K, Hoshiyama K, Nakura H, Kohno Y, Koike K, Okudaira H, Iwasaki E. Frequency of immediate-type food allergy in children in Japan. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999; 118:251–252.

12. Marrugo J, Hernández L, Villalba V. Prevalence of self-reported food allergy in Cartagena (Colombia) population. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2008; 36:320–324.

13. Liu AH, Jaramillo R, Sicherer SH, Wood RA, Bock SA, Burks AW, Massing M, Cohn RD, Zeldin DC. National prevalence and risk factors for food allergy and relationship to asthma: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126:798–806.e13.

14. Eller E, Kjaer HF, Høst A, Andersen KE, Bindslev-Jensen C. Food allergy and food sensitization in early childhood: results from the DARC cohort. Allergy. 2009; 64:1023–1029.

15. Jung YH, Ko H, Kim HY, Seo JH, Kwon JW, Kim BJ, Kim HB, Lee SY, Jang GC, Song DJ, Kim WK, Shim JY, Hong SJ. Prevalence and risk factors of food allergy in preschool children in Seoul. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 31:177–183.

16. Han Y, Kim J, Ahn K. Food allergy. Korean J Pediatr. 2012; 55:153–158.

17. Al-Hammadi S, Al-Maskari F, Bernsen R. Prevalence of food allergy among children in Al-Ain city, United Arab Emirates. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010; 151:336–342.

18. Dalal I, Binson I, Reifen R, Amitai Z, Shohat T, Rahmani S, Levine A, Ballin A, Somekh E. Food allergy is a matter of geography after all: sesame as a major cause of severe IgE-mediated food allergic reactions among infants and young children in Israel. Allergy. 2002; 57:362–365.

19. Kagan RS, Joseph L, Dufresne C, Gray-Donald K, Turnbull E, Pierre YS, Clarke AE. Prevalence of peanut allergy in primary-school children in Montreal, Canada. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 112:1223–1228.

20. Grundy J, Matthews S, Bateman B, Dean T, Arshad SH. Rising prevalence of allergy to peanut in children: data from 2 sequential cohorts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 110:784–789.

21. Mullins RJ, Dear KB, Tang ML. Characteristics of childhood peanut allergy in the Australian Capital Territory, 1995 to 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 123:689–693.

22. Shek LP, Cabrera-Morales EA, Soh SE, Gerez I, Ng PZ, Yi FC, Ma S, Lee BW. A population-based questionnaire survey on the prevalence of peanut, tree nut, and shellfish allergy in 2 Asian populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126:324–331. 331.e1–331.e7.

23. Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, Smith B, Kumar R, Pongracic J, Holl JL. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011; 128:e9–e17.

24. Steckelbroeck S, Ballmer-Weber BK, Vieths S. Potential, pitfalls, and prospects of food allergy diagnostics with recombinant allergens or synthetic sequential epitopes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 121:1323–1330.

25. Baatenburg de Jong A, Dikkeschei LD, Brand PL. High prevalence of sensitization to aeroallergens in children 4 yrs of age or younger with symptoms of allergic disease. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009; 20:735–740.

26. Zeiger RS, Heller S. The development and prediction of atopy in high-risk children: follow-up at age seven years in a prospective randomized study of combined maternal and infant food allergen avoidance. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995; 95:1179–1190.

27. Dalal I, Binson I, Levine A, Somekh E, Ballin A, Reifen R. The pattern of sesame sensitivity among infants and children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2003; 14:312–316.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download