Abstract

We presented a case of unusual endobronchial inflammatory polyps as a complication following endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) in a patient with tuberculous lymphadenitis. EBUS-TBNA of the right hilar lymph node was performed in a 29-year-old, previously healthy man. The patient was confirmed with tuberculous lymphadenitis and received antituberculosis medication over the course of 6 months. Chest computed tomography, after 6 months of antituberculosis therapy following the EBUS-TBNA showed nodular bronchial wall thickening of the right main bronchus. Histological and microbiological examinations revealed inflammatory polyps. After 7 months, the inflammatory polyps regressed almost completely without need for removal.

Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) is a useful technique for investigating patients with various mediastinal diseases123. Although EBUS-TBNA is generally considered to be safe, various complications are occasionally reported with the recent wide-spread use of EBUS-TBNA, including hemorrhage, infection, and inflammatory polyps456

Reports have described the successful removal of inflammatory polyps, which had developed after EBUS-TBNA, using biopsy forceps6. However, the natural clinical course of inflammatory polyps after EBUS-TBNA is still unclear. We report a patient with tuberculous lymphadenitis who developed inflammatory polyps 6 months after EBUS-TBNA, but did not undergo polyp removal, and discuss the natural progression of the polyps over the course of 7 months.

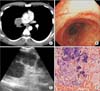

A 29-year-old man visited our clinic with a 1-month history of a dry cough and night sweats. He had been healthy and had no specific family medical history related to these symptoms. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed conglomerated, enlarged lymph nodes with central necrosis in the right upper paratracheal, both lower paratracheal, subcarinal, and right hilar areas (Figure 1A). Since no endobronchial lesion was visible on flexible bronchoscopy (BF-1T260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 1B), we performed EBUS-TBNA (BF-UC260FOL8; Olympus) to examine the right lower paratracheal and hilar lymph nodes histologically and microbiologically (Figure 1C). Chronic granulomatous inflammation with necrosis was evident (Figure 1D), and the EBUS-TBNA samples stained positively for acid-fast bacilli (AFB). As the histological findings of tuberculosis and positive AFB staining were compatible, we prescribed standard anti-tuberculosis treatment. Subsequently, although the post-bronchoscopy sputum specimen stained negatively for AFB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis was cultured. Sputum tests performed 1 month after initiating anti-tuberculosis treatment were AFB staining- and culture-negative.

After 6 months of antituberculosis treatment, CT was performed to assess the patient's response to treatment. Although the lymph nodes had decreased in size in comparison with the baseline CT, new endobronchial lesions were discovered in the right main bronchus (Figure 2). Flexible bronchoscopy showed lobulating endobronchial lesions in the distal right main bronchus and right secondary carina (Figure 2B). A forceps biopsy of the endobronchial lesions revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation (Figure 2C). AFB cultures and tuberculosis-polymerase chain reaction using bronchial washing and tissue samples were negative. The lobulating endobronchial lesions were therefore diagnosed as endobronchial inflammatory polyps.

Since the patient was asymptomatic, we observed the natural course of the polyps without resorting to their removal. Flexible bronchoscopy was performed 3 months later and the size of the endobronchial inflammatory polyps was found to have significantly decreased (Figure 3A, B). Moreover, the endobronchial inflammatory polyps had almost disappeared on bronchoscopy after 7 months (Figure 3C, D).

No report has followed the natural course of endobronchial inflammatory polyps following EBUS-TBNA. Our case showed that endobronchial inflammatory polyps, as a complication of EBUS-TBNA, could regress spontaneously without treatment. Therefore, this report may help in the management of asymptomatic endobronchial inflammatory polyps following EBUS-TBNA.

According to Dixit et al.7, the stroma of inflammatory polyps has a variable appearance depending on the number of blood vessels, the nature of the connective tissue, and the severity of the inflammatory cellular infiltrate. Samter proposed a process explaining the development of the polyps; a variety of injuries including trauma, secondary infection, and sensitization to bacteria or to other agents leads to increased capillary permeability and the immigration of inflammatory cells, causing vascular congestion and tissue edema. The pressure of this fluid pushes the mucous membrane forward, giving rise first to folds and projections and then to massive mucosal herniates in the respiratory tract8.

Compatible bronchoscopic and histological findings are required to diagnose an inflammatory polyp910. In addition, both tuberculosis and inflammatory polyps show granulomatous inflammation histologically, making them difficult to distinguish using this technique alone. We observed that a polypoid lesion developed in the right bronchial tree after EBUS-TBNA. Staining of forceps biopsy material revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation. However, AFB cultures of polypoid tissue and a polymerase chain reaction for detecting M. tuberculosis were negative. Moreover, the inflammatory polypoid lesions essentially disappeared in the absence of further antituberculosis treatment. This means that the inflammatory polyps were attributable to EBUS-TBNA, and not tuberculous inflammation.

Cases of inflammatory polyps following EBUS-TBNA are rare. In a previous case, because the patient had symptoms, including cough and dyspnea, the inflammatory polyps had to be removed. Therefore, it was difficult to recognize the natural progression of the inflammatory polyps6. However, our patient was asymptomatic and so we were able to observe the natural course over several months without removing the polyps. As a result, the polyps spontaneously regressed.

In conclusion, we found that endobronchial inflammatory polyps after EBUS-TBNA can regress spontaneously without treatment. Unless endobronchial inflammatory polyps lead to respiratory symptoms, observation without removal of the polyps is a reasonable treatment option.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

A 29-year-old male with tuberculous lymphadenitis of the right upper paratracheal, both lower paratracheal, subcarinal, and right hilar lymph nodes. (A) Initial chest computed tomography shows conglomerated, enlarged lymph nodes with central necrosis in the right hilar area. (B) No endobronchial lesion was found at the right main bronchus or secondary carina on initial flexible bronchosocpy. (C) An endobronchial ultrasound image of the right lower paratracheal and hilar lymph nodes showed a hypoechoic texture, and transbronchial needle aspiration was performed under real-time ultrasound guidance. (D) The histopathology showed chronic granulomatous inflammation with necrosis (H&E stain, ×400).

Figure 2

Computed tomography was performed to assess the treatment response after 6 months of antituberculosis treatment. (A) A newly developed endobronchial lesion was found on computed tomography (arrows). (B) Lobulating nodular lesions at the distal right main bronchus and right secondary carina were noted on flexible bronchoscopy. (C) Forceps biopsy of the newly developed endobronchial lesions revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation (H&E stain, ×400).

Figure 3

The natural course of the inflammatory polyps. (A) After 3 months, flexible bronchoscopy indicated a decreased size of the endobronchial inflammatory polyps . (B) A narrow-band imaging bronchoscopic scan taken after 3 months. (C) After 7 months, the endo bronchial inflammatory polyps had spontaneously regressed almost com pletely. (D) A narrow-band imaging bronchoscopic scan taken after 7 months.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a clinical research grant from the Biomedical Research Institute, Pusan National University Hospital (2015).

References

1. Navani N, Molyneaux PL, Breen RA, Connell DW, Jepson A, Nankivell M, et al. Utility of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in patients with tuberculous intrathoracic lymphadenopathy: a multicentre study. Thorax. 2011; 66:889–893.

2. Kokkonouzis I, Strimpakos AS, Lampaditis I, Tsimpoukis S, Syrigos KN. The role of endobronchial ultrasound in lung cancer diagnosis and staging: a comprehensive review. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012; 13:408–415.

3. Kang HJ, Hwangbo B. Technical aspects of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2013; 75:135–139.

4. Asano F, Aoe M, Ohsaki Y, Okada Y, Sasada S, Sato S, et al. Complications associated with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a nationwide survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy. Respir Res. 2013; 14:50.

5. von Bartheld MB, van Breda A, Annema JT. Complication rate of endosonography (endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound): a systematic review. Respiration. 2014; 87:343–351.

6. Gupta R, Park HY, Kim H, Um SW. Endobronchial inflammatory polyp as a rare complication of endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010; 11:340–341.

7. Dixit R, George J, Dave L, Rai SM. Endobronchial inflammatory polyp. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2010; 11:312–315.

8. Samter M. Nasal polyps: an inquiry into the mechanism of formation. Arch Otolaryngol. 1961; 73:334–341.

9. Smith RE. Endobronchial polyp and chronic smoke injury. Postgrad Med J. 1989; 65:785–787.

10. Rosenberg JC. Bronchial polyps of inflammatory origin. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1969; 57:848–852.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download