Abstract

Background

Estimation of the probability of a patient having an acute pulmonary embolism (PE) for patients with a suspected PE are well established in North America and Europe. However, an assessment of the prediction rules for a PE has not been clearly defined in Korea. The aim of this study is to assess the prediction rules for patients with a suspected PE in Korea.

Methods

We performed a retrospective study of 210 inpatients or patients that visited the emergency ward with a suspected PE where computed tomography pulmonary angiography was performed at a single institution between January 2005 and March 2007. Simplified Wells rules and revised Geneva rules were used to estimate the clinical probability of a PE based on information from medical records.

Results

Of the 210 patients with a suspected PE, 49 (19.5%) patients had an actual diagnosis of a PE. The proportion of patients classified by Wells rules and the Geneva rules had a low probability of 1% and 21%, an intermediate probability of 62.5% and 76.2%, and a high probability of 33.8% and 2.8%, respectively. The prevalence of PE patients with a low, intermediate and high probability categorized by the Wells rules and Geneva rules was 100% and 4.5% in the low range, 18.2% and 22.5% in the intermediate range, and 19.7% and 50% in the high range, respectively. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis showed that the revised Geneva rules had a higher accuracy than the Wells rules in terms of detecting PE. Concordance between the two prediction rules was poor (κ coefficient=0.06).

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

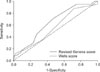

Comparison of the predictive accuracy of the two methods for pulmonary embolism. (A) Specificity and sensitivity of Wells score, (B) Sensitivity and specificity of revised Geneva score.

Figure 2

ROC curve (Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) of Wells scoreand revised Geneva score. Area under the ROC curve=0.56 (95% CI: 0.46 to 0.66) for Wells score, area under the ROC curve=0.64 (95% CI: 0.55 to 0.73) for revised Geneva score.

Table 3

Proportions of patients and frequency of pulmonary embolism in the two clinical probabilities

References

1. Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Patwardhan NA, Jovanovic B, et al. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991. 151:933–938.

2. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Ginsberg JS, Kearon C, Gent M, et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000. 83:416–420.

3. Wicki J, Perneger TV, Junod AF, Bounameaux H, Perrier A. Assessing clinical probability of pulmonary embolism in the emergency ward: a simple score. Arch Intern Med. 2001. 161:92–97.

4. Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, Gottschalk A, Hales CA, Hull RD, et al. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006. 354:2317–2327.

5. Kim TW, Kim WK, Lee JH, Kim SB, Kim SW, Suh C, et al. Low prevalence of activated protein C resistance and coagulation factor V Arg506 to Gln mutation among Korean patients with deep vein thrombosis. J Korean Med Sci. 1998. 13:587–590.

6. Choi WI, Park JS, Min BR, Park JH, Chae JN, Jeon YJ, et al. Estimated incidence of acute pulmonary embolism in a university teaching hospital. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2007. 63:suppl 2. 68.

7. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, Sanchez O, Aujesky D, Bounameaux H, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006. 144:165–171.

8. Chagnon I, Bounameaux H, Aujesky D, Roy PM, Gourdier AL, Cornuz J, et al. Comparison of two clinical prediction rules and implicit assessment among patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Med. 2002. 113:269–275.

9. Moores LK, Collen JF, Woods KM, Shorr AF. Practical utility of clinical prediction rules for suspected acute pulmonary embolism in a large academic institution. Thromb Res. 2004. 113:1–6.

10. Sanson BJ, Lijmer JG, Mac Gillavry MR, Turkstra F, Prins MH, Buller HR. Comparison of a clinical probability estimate and two clinical models in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. ANTELOPE-Study Group. Thromb Haemost. 2000. 83:199–203.

11. Kruip MJ, Slob MJ, Schijen JH, van der Heul C, Buller HR. Use of a clinical decision rule in combination with D-dimer concentration in diagnostic workup of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a prospective management study. Arch Intern Med. 2002. 162:1631–1635.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download