Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to assess and identify gender differences in factors associated with prevalence, awareness, and treatment of osteoporosis.

Methods

Data for 3,071 men and 3,635 women (age≥ 50) from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008~2011 were included. Osteoporosis was defined by World Health Organization T-score criteria. Impact factors and odds ratios were analysed by gender using multivariate logistic regression.

Results

Osteoporosis prevalence rates were 7.0% in men and 40.1% in women. Osteopenia rates were 45.5% and 46.0% respectively. Among respondents with osteoporosis, 7.6% men and 37.8% women were aware of their diagnosis. Also 5.7% men with osteoporosis and 22.8% women were treated. Higher prevalence was found among respondents who were older, at lower socioeconomic levels, with lower body mass index and shorter height in both genders, and among women with fracture history, and non-hormonal replacement therapy. Awareness and treatment rates for the risk groups were similar compared to the low risk controls for both genders. Fracture history increased awareness and treatment rates independently for both genders. Women with perceived poor health status and health screening had increased awareness and treatment rates, but not men.

Conclusion

Results indicate that postmenopausal women have a higher prevalence of osteoporosis than men and awareness and treatment rates were higher than for men. Despite gender difference in prevalence, osteoporosis was underdiagnosed and undertreated for both genders. Specialized public education and routine health screenings according to gender could be effective strategies to increase osteoporosis awareness and treatment.

Figures and Tables

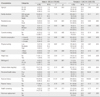

Table 5

Odds ratios for Osteoporosis Prevalence, Awareness and Treatment by Gender

OR=Odds ratio; CI=Confidence interval; OFM=Other family members; SES=Socioeconomic status; BMI=Body mass index; n=Unweighted sample size; N=weighted sample size; All data were weighted to the residential population of Korea; *p<.05; †p<.001; ‡Among persons with lumbar spine or femoral neck T-score≤ -2.5, or taking anti-osteoporotic medications.

References

1. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994; 843:1–129.

2. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001; 285(6):785–795.

3. WHO Scientific Group on the Burden of Musculoskeletal Conditions at the Start of the New Millennium. The burden of musculoskeletal conditions at the start of the new millennium. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2003; 919:i–x.

4. Oh HJ. Development of guideline for life cycle osteoporosis health care. Osong: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2011.

5. Cawthon PM. Gender differences in osteoporosis and fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011; 469(7):1900–1905. DOI: 10.1007/s11999-011-1780-7.

6. Lips P, van Schoor NM. Quality of life in patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2005; 16(5):447–455. DOI: 10.1007/s00198-004-1762-7.

7. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. A dramatic increase of elderly osteoporotic patients [Internet]. Seoul: Author;2013. cited 2013 February 22. Available from: http://www.hira.or.kr/dummy.do?pgmid=HIRAA02004100000&cmsurl=/cms/notice/02/1316013_13390.html&subject.

8. Alswat K, Adler SM. Gender differences in osteoporosis screening: Retrospective analysis. Arch Osteoporos. 2012; 7(1-2):311–313. DOI: 10.1007/s11657-012-0113-0.

9. Park EJ, Joo IW, Jang MJ, Kim YT, Oh K, Oh HJ. Prevalence of osteoporosis in the Korean population based on Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), 2008-2011. Yonsei Med J. 2014; 55(4):1049–1057. DOI: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.4.1049.

10. Lee SR, Kim SR, Chung KH, Ko DO, Cho SH, Ha YC, et al. Mortality and activity after hip fracture: A prospective study. J Korean Orthop Assoc. 2005; 40(4):423–427.

11. Hawkes WG, Wehren L, Orwig D, Hebel JR, Magaziner J. Gender differences in functioning after hip fracture. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006; 61(5):495–499.

12. Lee K. Evidence-based management for osteoporosis. J Korean Med Assoc. 2011; 54(3):294–302. DOI: 10.5124/jkma.2011.54.3.294.

13. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, et al. Data resource profile: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43(1):69–77. DOI: 10.1093/ije/dyt228.

14. Kim KH, Lee K, Ko YJ, Kim SJ, Oh SI, Durrance DY, et al. Prevalence, awareness, and treatment of osteoporosis among Korean women: The fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Bone. 2012; 50(5):1039–1047. DOI: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.02.007.

15. Kim JY, Kim SH, Cho YJ. Socioeconomic status in association with metabolic syndrome and coronary heart disease risk. Korean J Fam Med. 2013; 34(2):131–138. DOI: 10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.2.131.

16. International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): Short and long forms [Internet]. Huddinge, SE: Author;2005. cited 2014 June 20. Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol/scoring_protocol.pdf.

17. The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary reference intakes for Koreans. Seoul: Author;2010.

18. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Paper presented at: The 5th Data Analysis Conference. 2014 July 2; aT Center Conference Room (L). Seoul.

19. Lee J, Lee S, Jang S, Ryu OH. Age-related changes in the prevalence of osteoporosis according to gender and skeletal site: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008-2010. Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 28(3):180–191. DOI: 10.3803/EnM.2013.28.3.180.

20. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, et al. Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014; 25(10):2359–2381. DOI: 10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2.

21. Kao CH, Chen CC, Wang SJ. Normal data for lumbar spine bone mineral content in healthy elderly Chinese: Influences of sex, age, obesity and ethnicity. Nucl Med Commun. 1994; 15(11):916–920.

22. Russell-Aulet M, Wang J, Thornton JC, Colt EW, Pierson RN, Jr . Bone mineral density and mass in a cross-sectional study of white and Asian women. J Bone Miner Res. 1993; 8(5):575–582. DOI: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080508.

23. Haaland DA, Cohen DR, Kennedy CC, Khalidi NA, Adachi JD, Papaioannou A. Closing the osteoporosis care gap: Increased osteoporosis awareness among geriatrics and rehabilitation teams. BMC Geriatr. 2009; 9:28. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2318-9-28.

24. Seo SY, Lee JS. Influence of knowledge and subjective health status on health promoting behavior about osteoporosis in industrial workers. J Muscle Joint Health. 2012; 19(3):340–349. DOI: 10.5953/JMJH.2012.19.3.340.

25. Jennings LA, Auerbach AD, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK, Lee SJ. Missed opportunities for osteoporosis treatment in patients hospitalized for hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010; 58(4):650–657. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02769.x.

26. Kiebzak GM, Beinart GA, Perser K, Ambrose CG, Siff SJ, Heggeness MH. Undertreatment of osteoporosis in men with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162(19):2217–2222.

27. Majumdar SR, Beaupre LA, Harley CH, Hanley DA, Lier DA, Juby AG, et al. Use of a case manager to improve osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167(19):2110–2115. DOI: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2110.

28. Song MS, Yoo YK, Choi CH, Kim NC. Effects of Nordic walking on body composition, muscle strength, and lipid profile in elderly women. Asian Nurs Res. 2013; 7(1):1–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.anr.2012.11.001.

29. Yoo YW, Lee EN. The influencing factors of the compliance level with therapeutic regimen after the bone mineral densitometry. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2004; 34(1):63–71.

30. Lee HY, Kim SY. The effect of education for prevention of osteoporosis patients with bone fracture. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2001; 31(2):194–205.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download