Figures and Tables

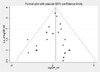

Fig. 1

A funnel plot of log odds ratios (ORs) of the incidence of myocardial infarction between rosiglitazone group and control group versus its standard error (SE). Data used was from the 42 trials displayed in Table 3 of Nissen and Wolski (2007).

Fig. 2

A graphical representation of the concepts of (a) a fixed-effects model and (b) a random-effects model. A fixed-effects model assumes that there is a common 'true' treatment effect underlying studies and that each study result will vary randomly around this true effect (i.e., treatment effect for each study = common true treatment effect + study variation that called a random error). A random-effects model assumes that there is different underlying effect for each study and that there is also an additional source of variation between studies which reflects the amount of heterogeneity between them (i.e., treatment effect for each study = true average effect which follows a normal distribution + within study variation that called a random error).

Fig. 3

A sample result of meta-analysis for the odds ratio (OR) of myocardial infarction (MI) between rosiglitazone group and control group using STATA software based on the data from the Table 3 of Nissen and Wolski (2007). Peto estimation method is used to combine the results of 38 trials. Four trials are excluded in the meta-analysis due to zero events observed in both groups.

Fig. 4

A forest plot and the combined result of meta-analysis for the odds ratio (OR) of myocardial infarction (MI) between rosiglitazone group and control group. A fixed-effects model with Peto estimation method is used. Each of blocks represents the OR for each trial and the horizontal line indicates its 95% confidence interval (CI). The size of each block is approximately proportional to the statistical weight of the trial used in the meta-analysis. The diamond represents the pooled estimate and its 95% CI. The solid vertical line indicates no difference in the odds of MI between two groups, while the dashed vertical line represents the pooled effect. The left side of the solid vertical line represents lower odds of MI for rosiglitazone than for control, while the right side represents higher odds. Four trials are excluded in the meta-analysis due to zero events observed in both groups.

Fig. 5

A plot for finding most influential trial in the result of meta-analysis for the odds ratio (OR) of myocardial infarction (MI) between rosiglitazone group and control group. Each of horizontal line indicates a repeated result of meta-analysis after omitting the corresponding trial in turn. Vertical solid lines represent Peto's pooled estimate and its 95% confidence interval using all of 38 trials.

Table 1

Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE. Following examples are adapted from Higgins and Green (2008)

References

1. Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. NEJM. 2007. 356:2457–2471.

2. Psaty BM, Furberg CD. Rosiglitazone and cardiovascular risk. NEJM. 2007. 356:2522–2524.

3. Psaty BM, Furberg CD. The record on rosiglitazone and the risk of myocardial infarction. NEJM. 2007. 357:67–69.

4. The RECORD study group. Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes-an interim analysis. NEJM. 2007. 357:28–38.

5. Drazen JM, Morrissey S, Curfman GD. Rosiglitazone-continued uncertainty about safety. NEJM. 2007. 357:63–64.

6. Nathan DM. Rosiglitazone and cardiotoxicity-weighing the evidence. NEJM. 2007. 357:64–66.

7. Rosen CJ. The rosiglitazone story - Lessons from an FDA advisory committee meeting. NEJM. 2007. 357:844–846.

8. Letters to the editor: Rosiglitazone and cardiovascular risk. NEJM. 2007. 357:930–940.

9. Letters to the editor: Rosiglitazone and the FDA. NEJM. 2007. 357:1775–1777.

10. The ACCORD study group. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. NEJM. 2008. 358:2545–2559.

11. The ADVANCE collaborative group. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. NEJM. 2008. 358:2560–2572.

12. Goldfine AB. Assessing the cardiovascular safety of diabetes therapies. NEJM. 2008. 359:1092–1095.

13. Pearson K. Report on certain enteric fever inoculation statistics. BMJ. 1904. 3:1243–1246.

14. Egger M, Davey Smith G. Meta-analysis: potentials and premise. BMJ. 1997. 315:1371–1374.

15. Lasagna L, Mosteller F, von Felsinger JM, Beecher HK. A study on the placebo response. Am J Med. 1954. 16:770–779.

16. Glass GV. Primary, secondary and meta-analysis of research. Edu Res. 1976. 5:3–8.

17. Cochrane AL. Effectiveness and efficiency: Random reflections on the health service. 1972. London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust.

18. Cochrane AL. 1931-1971: A critical review, with particular reference to the medical profession. Medicines for the year 2000. 1979. London: Office of Health Economics;1–11.

19. Chalmers I, Sackett D, Silagy C, Maynard A, Chalmers TC. Non-random reflections on health services research. 1997. London: BMJ Publishing Group.

20. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence-based medicine: what is it and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996. 312:71–72.

21. Lee JY. Medical Statistics at a Glance. 2007. Seoul: Epublic.

22. Sackett DL, Straus S, Richardson S, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2000. 2nd ed. London: Churchill-Livingston.

23. Greenhalgh T. Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses). BMJ. 1997. 315:672–675.

24. DerSimonian R, Laird NM. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986. 7:177–186.

25. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman D. Systematic reviews in health care: Meta-analysis in context. 2001. London: BMJ Publishing Group.

26. L'Abbe KA, Detsky AS, O'Rourke K. Meta-analysis in clinical research. Ann Intern Med. 1987. 107:224–233.

27. Meade MO. Selecting and appraising studies for a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 1997. 127:531–537.

28. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. version 5.0.0. 2008. Accessed Nov 28, 2008. The Cochrane Collaboration;Available from

http://www.cochrane-handbook.org.

29. Counseil C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997. 127:380–387.

30. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Phillips AN. Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. BMJ. 1997. 315:1533–1537.

31. Simes RJ. Confronting publication bias: a cohort design for meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1987. 6:11–29.

32. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997. 315:629–634.

33. Greenland S. Invited commentary: a critical look at some popular meta-analytic methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1994. 140:290–296.

34. Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias: Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995. 273:408–412.

35. Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, Tugwell P, Klassen TP. Does quality of reports of randomized trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 1998. 352:609–613.

36. Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell P, Walsh S. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: an annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clin Trials. 1995. 16:62–73.

37. Juni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA. 1999. 282:1054–1060.

38. Moher D, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Tugwell P, Moher M, Jones A, Pham B, Klassen TP. Assessing the quality of reports of randomised trials: implications for the conduct of meta-analyses. Health Technol Assess. 1999. 3:i–iv. 1–98.

39. Chalmers TC, Smith H, Blackburn B, Silverman B, Schroeder B, Reitman D, Ambroz A. A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials. 1981. 2:31–49.

40. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay H. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996. 17:1–12.

41. Stewart LA, Clarke M. Practical methodology of meta-analysis (overviews) using updated individual patient data: Cochrane Working Group. Stat Med. 1995. 14:2057–2079.

42. Cochrane Collaboration Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis Methods Group. Accessed Nov 28, 2008.

http://www.ctu.mrc.ac.uk/cochrane/ipdmg/.

43. Hedges LV. Statistical Methodology in Meta-Analysis. 1982. Princeton: Educational Testing Service.

44. Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for meta-analysis in medical research. 2000. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

45. Fleiss JL. The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 1993. 2:121–145.

46. Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954. 10:101–129.

47. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks J, Altman DG. Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002. 7:51–61.

48. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks J, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003. 327:557–560.

49. Fleiss JL. Analysis of data from multiclinic trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986. 7:267–275.

50. Furberg CT, Morgan TM. Lessons from overviews of cardiovascular trials. Stat Med. 1987. 6:295–303.

51. Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. A consumer's guide to subgroup analyses. Ann Intern Med. 1992. 116:78–84.

52. Schmid CH. Exploring heterogeneity in randomized trials via meta-analysis. Drug Info J. 1999. 33:211–224.

53. Glasziou PP, Sanders SL. Investigating causes of heterogeneity in systematic reviews. Stat Med. 2002. 21:1503–1511.

54. Song F. Exploring heterogeneity in meta-analysis: is the L'Abbe plot useful? J Clin Epidemiol. 1999. 52:725–730.

55. Galbraith RF. A note on the graphical presentation of estimated odds ratio from several clinical trials. Stat Med. 1988. 7:889–894.

56. Thompson SG. Controversies in meta-analysis: the case of the trials of serum cholesterol reduction. Stat Methods Med Res. 1993. 2:173–192.

57. The QUOROM group. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Lancet. 1999. 354:1896–1900.

58. The MOOSE group. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology. a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000. 283:2008–2012.

59. Egger M, Davey Smith G. Bias in location and selection of studies. BMJ. 1998. 316:61–66.

60. Song F, Eastwood AJ, Gilbody S, Duley L, Sutton AJ. Publication and related biases. Health Technol Assess. 2000. 4:1–105.

61. Shapiro S. Meta-analysis/Shmeta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1994. 140:771–778.

62. LeLorier J, Gregoire G, Benhaddad A, Lapierre J, Derderian F. Discrepancies between meta-analyses and subsequent large randomized, controlled trials. NEJM. 1997. 337:536–542.

63. Rosenfeld RM, Post JC. Meta-analysis of antibiotics for the treatment of otitis media with effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992. 106:378–386.

64. Williams RL, Chalmers TC, Strange KC, Chalmers FT, Bowlin SJ. Use of antibiotics in preventing recurrent acute otitis media and in treating otitis media with effusion: a meta-analytic attempt to resolve the brouhaha. JAMA. 1993. 270:1344–1351.

65. Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Rubin SM, Sandrick C, Ernster VL. Efficacy of screening mammography: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995. 273:149–154.

66. Smart CR, Hendrick RE, Rutledge JH, Smith RA. Benefit of mammography screening in women ages 40 to 49 years: current evidence from randomized controlled trials. Cancer. 1995. 75:1619–1626.

67. Cook DJ, Mulrow CD, Haynes RB. Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Int Med. 1997. 126:376–380.

68. Davey Smith G, Egger M. Meta-analysis: unresolved issues and future developments. BMJ. 1998. 316:221–225.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download