1. Song SO, Lee YH, Kim DW, Song YD, Nam JY, Park KH, et al. Trends in diabetes incidence in the last decade based on Korean National Health Insurance claims data. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2016; 31:292–299. PMID:

27302715.

2. Laaksonen DE, Lakka HM, Niskanen LK, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT, Lakka TA. Metabolic syndrome and development of diabetes mellitus: application and validation of recently suggested definitions of the metabolic syndrome in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002; 156:1070–1077. PMID:

12446265.

3. Ford ES, Li C. Metabolic syndrome and health-related quality of life among U.S. adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2008; 18:165–171. PMID:

18280918.

4. Primeau V, Coderre L, Karelis AD, Brochu M, Lavoie ME, Messier V, et al. Characterizing the profile of obese patients who are metabolically healthy. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011; 35:971–981. PMID:

20975726.

6. Park YA, Jeong SH, Yoon SH, Choi YH, Song KB. Associations between general health and diet habits and oral health among the elderly in Pohang city. J Korean Acad Oral Health. 2006; 30:183–192.

7. Casanova L, Hughes FJ, Preshaw PM. Diabetes and periodontal disease: a two-way relationship. Br Dent J. 2014; 217:433–437. PMID:

25342350.

8. Wakai K, Kawamura T, Umemura O, Hara Y, Machida J, Anno T, et al. Associations of medical status and physical fitness with periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1999; 26:664–672. PMID:

10522778.

9. American Academy of Periodontology. Parameter on systemic conditions affected by periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2000; 71(Suppl 5S):880–883.

10. Loesche WJ. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for heart disease. Compendium. 1994; 15:976978–982. 985–986 passim. quiz 992. PMID:

7741856.

11. McFall WT Jr. Tooth loss in 100 treated patients with periodontal disease. A long-term study. J Periodontol. 1982; 53:539–549. PMID:

6957591.

12. Khader Y, Khassawneh B, Obeidat B, Hammad M, El-Salem K, Bawadi H, et al. Periodontal status of patients with metabolic syndrome compared to those without metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol. 2008; 79:2048–2053. PMID:

18980512.

13. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Preventive. Korea Health Statistics 2015: Korean National Health and Nutritional Examination survey (KNHANES VI-3). Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2015. p. 298.

14. Song IS, Han K, Ryu JJ, Park JB. Association between underweight and tooth loss among Korean adults. Sci Rep. 2017; 7:41524. PMID:

28128349.

15. Kim SW, Cho KH, Han KD, Roh YK, Song IS, Kim YH. Tooth loss and metabolic syndrome in South Korea: The 2012 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95:e3331. PMID:

27100416.

16. HJ Kang. A study on periodontal disease and tooth loss in metabolic syndrome patient. J Dent Hyg Sci. 2015; 15:445–446.

17. Shim JS, Song BM, Lee JH, Lee SW, Park JH, Choi DP, et al. Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center (CMERC) cohort: study protocol and results of the first 3 years of enrollment. Epidemiol Health. 2017; 39:e2017016. PMID:

28395401.

18. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001; 285:2486–2497. PMID:

11368702.

19. Jin HJ, Bae KH, Kim JB, Park DY, Jeong SH, Kim BI, et al. Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for evaluating periodontal disease. J Korean Acad Oral Health. 2014; 38:170–175.

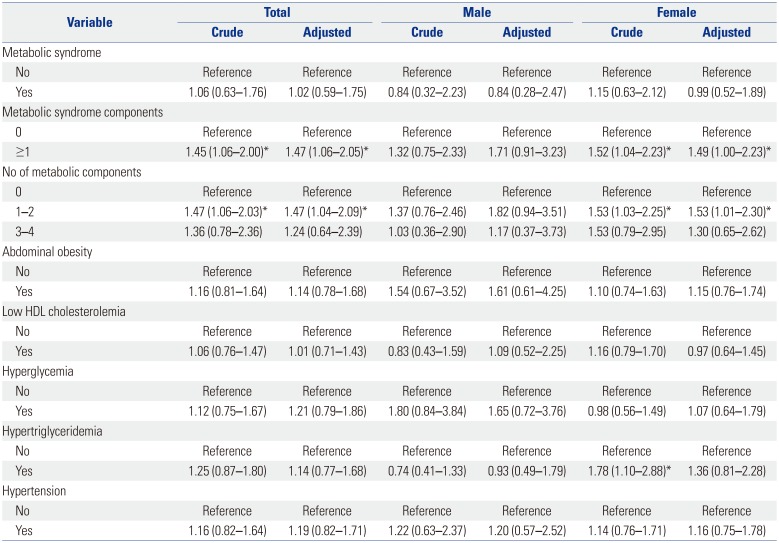

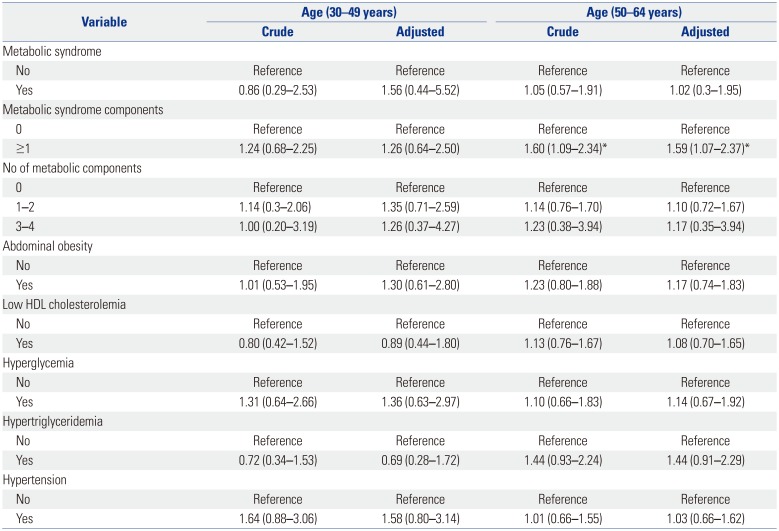

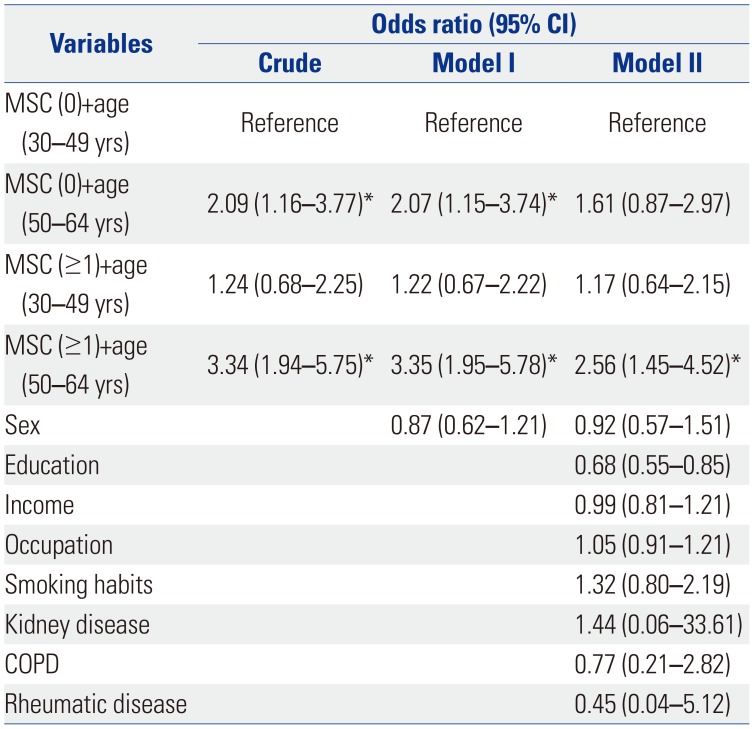

20. Cho MJ, Shim JS, Kim HC, Song KB, Choi YH. Relationship between metabolic syndrome components and periodontal health determined using a self-reported questionnaire. J Korean Acad Oral Health. 2016; 40:231–237.

21. Na DW, Jeong E, Noh EK, Chung JS, Choi CH, Park J. Dietary factors and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged men. J Agr Med Commun Health. 2010; 35:388–394.

22. Arai H, Yamamoto A, Matsuzawa Y, Saito Y, Yamada N, Oikawa S, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in elderly and middle-aged Japanese. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2010; 1:42–47.

23. Sheiham A, Nicolau B. Evaluation of social and psychological factors in periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2005; 39:118–131. PMID:

16135067.

24. Cairo F, Nieri M, Gori AM, Rotundo R, Castellani S, Abbate R, et al. Periodontal variables may predict sub-clinical atherosclerosis and systemic inflammation in young adults. A cross-sectional study. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2009; 2:125–133. PMID:

20467611.

25. Nakarai H, Yamashita A, Takagi M, Adachi M, Sugiyama M, Noda H, et al. Periodontal disease and hypertriglyceridemia in Japanese subjects: potential association with enhanced lipolysis. Metabolism. 2011; 60:823–829. PMID:

20817211.

26. Gurav AN. The association of periodontitis and metabolic syndrome. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2014; 11:1–10. PMID:

24688553.

27. Nishimura F, Soga Y, Iwamoto Y, Kudo C, Murayama Y. Periodontal disease as part of the insulin resistance syndrome in diabetic patients. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2005; 7:16–20. PMID:

15736891.

28. Morita T, Yamazaki Y, Mita A, Takada K, Seto M, Nishinoue N, et al. A cohort study on the association between periodontal disease and the development of metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol. 2010; 81:512–519. PMID:

20367094.

29. Joshipura KJ, Rimm EB, Douglass CW, Trichopoulos D, Ascherio A, Willett WC. Poor oral health and coronary heart disease. J Dent Res. 1996; 75:1631–1636. PMID:

8952614.

30. Kang HJ, Yul BC. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and oral diseases in the middle aged and elderly people. J Korean Soc Dent Hyg. 2015; 15:947–961.

31. Kaye EK, Chen N, Cabral HJ, Vokonas P, Garcia RI. Metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease progression in men. J Dent Res. 2016; 95:822–828. PMID:

27025874.

32. Furuta M, Liu A, Shinagawa T, Takeuchi K, Takeshita T, Shimazaki Y, et al. Tooth loss and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged Japanese adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2016; 43:482–491. PMID:

26847391.

33. Zhu Y, Hollis JH. Associations between the number of natural teeth and metabolic syndrome in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2015; 42:113–120. PMID:

25581485.

34. Ojima M, Amano A, Kurata S. Relationship Between Decayed Teeth and Metabolic Syndrome: Data From 4716 Middle-Aged Male Japanese Employees. J Epidemiol. 2015; 25:204–211. PMID:

25716056.

35. Musskopf ML, Daudt LD, Weidlich P, Gerchman F, Gross JL, Oppermann RV. Metabolic syndrome as a risk indicator for periodontal disease and tooth loss. Clin Oral Investig. 2017; 21:675–683.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download