Abstract

Purpose

Prior abdomino-pelvic (AP) surgery makes colonoscopy difficult and can affect bowel preparation quality. However, bowel preparation quality has been found to vary according to prior AP surgery type. We examined the relationship of prior AP surgery type with bowel preparation quality in a large-scale retrospective cohort.

Materials and Methods

In the health screening cohort of the National Cancer Center, 12881 participants who underwent screening or surveillance colonoscopy between June 2007 and December 2014 were included. Personal data were collected by reviewing patient medical records. Bowel preparation quality was assessed using the Aronchick scale and was categorized as satisfactory for excellent to good bowel preparation or unsatisfactory for fair to inadequate bowel preparation.

Results

A total of 1557 (12.1%) participants had a history of AP surgery. The surgery types were colorectal surgery (n=44), gastric/small intestinal surgery (n=125), appendectomy/peritoneum/laparotomy (n=476), cesarean section (n=278), uterus/ovarian surgery (n=317), kidney/bladder/prostate surgery (n=19), or liver/pancreatobiliary surgery (n=96). The proportion of satisfactory bowel preparations was 70.7%. In multivariate analysis, unsatisfactory bowel preparation was related to gastric/small intestinal surgery (odds ratio=1.764, 95% confidence interval=1.230–2.532, p=0.002). However, the other surgery types did not affect bowel preparation quality. Current smoking, diabetes, and high body mass index were risk factors of unacceptable bowel preparation.

Although there are different tests for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, colonoscopy is the most effective method for ruling out precancerous colonic lesions and for preventing cancer by allowing removal of adenomatous lesions during endoscopic examinations.123 Furthermore, colonoscopy is the standard method for examining most diseases of the colon.45 Despite the necessity of colonoscopy, patients are often reluctant to receive colonoscopy because of the inconvenience of bowel preparation and discomfort during colonoscopy.

Adequate bowel preparation is an important factor in determining the diagnostic yield, difficulty, procedure time, and completeness of colonoscopy.6 Prior abdominal or pelvic surgery is related to difficult colonoscopy, which may prolong the procedure, necessitate the need for more sedation and analgesia for the patient, and increase the risks of complications.789 Accordingly, adequate bowel preparation in patients with a prior abdominal or pelvic surgery is very important.

To date, only four studies have evaluated whether prior abdominal or pelvic surgery affects bowel preparation quality for colonoscopy.10111213 A recent prospective study from Korea suggests that a history of colorectal resection, appendectomy, and hysterectomy is associated with poor bowel preparation.13 Among abdomino-pelvic (AP) surgeries, colectomy comes out consistently as a poor prognostic factor for bowel preparation. However, a history of other AP surgeries has shown different results among studies.10111213 In addition, it is still unclear what kind of surgical procedures affects bowel preparation quality for colonoscopy, owing to the ambiguity of the descriptions in each study regarding the types of abdomino-pelvic surgery, including its range. Furthermore, the number of enrolled subjects was as small as 184–362 in prospective studies and 2811 in a retrospective study.

Therefore, in this study, we examined the relationship of patient factors (e.g., type of prior AP surgery) with bowel preparation quality in a large-scale retrospective cohort.

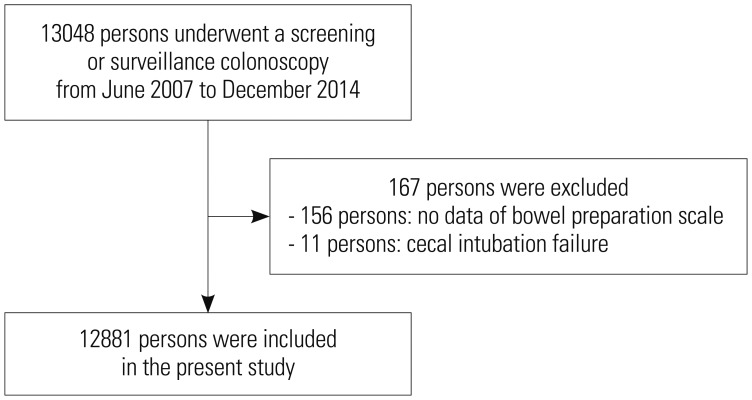

The protocols of the research were approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Cancer Center (NCC2015-0281). This study was a retrospective cohort study using a large self-motivated health screening cohort from the National Cancer Center, Korea.14 Participants underwent colonoscopies for screening or surveillance after polypectomy without symptoms. The flow of inclusion and exclusion of the study population is described in Fig. 1. We included 13048 participants who underwent screening or surveillance colonoscopy and completed questionnaires from June 2007 to December 2014. We excluded 167 participants who had no data on bowel preparation (n=156) and experienced failed cecal intubation (n=11). Therefore, 12881 participants were included in the present study. Personal data were collected by reviewing patient medical records that contained information on age, sex, medical history, smoking status, drinking status, and colonoscopy findings with pathologic results.

All patients were educated to follow a low-fiber diet for 3 days before the test and a liquid diet at dinner on the day before, while fasting over midnight. The medications used in this study were Fleet Phospho-soda (NaP), 4-L polyethylene glycol (4L-PEG), Coolprep (2-L PEG+Ascorbic acid, 2L-PEG+Asc), Picolight (Sodium picosulfate-magnesium citrate, SPMC).

In the NaP group, the participants ingested 45 mL of aqueous Fleet Phospho-soda (Fleet Company, Inc., Lynchburg, VA, USA) in 240 mL of water, followed by 1500 mL of water at 7 pm the day before colonoscopy. They ingested another 45 mL of aqueous Fleet Phospho-soda (NaP) in 240 mL of water, followed by 1500 mL of water at 10 pm. In the 4-L PEG group, the patients ingested 4 L of PEG (Taejoon Pharmaceuticals, Seoul, Korea; 236 g PEG, 22.74 g Na2SO4, 6.74 g NaHCO3, 5.86 g NaCl, and 2.97 g KCl), starting at 6 am on the day of colonoscopy. All patients were asked to drink PEG at a rate of 200 mL/10 min. In the SPMC group, the participants ingested Picolight (Pharmbio Korea, Seoul, Korea), which consists of 10 mg of sodium picosulfate hydrate, 3.5 g of magnesium oxide, and 12 g of citric acid, and water the day before colonoscopy at 7 pm, followed by 2000 mL of water at 10 pm. In the 2L-PEG+Asc group, the participants ingested Coolprep (Taejoon Pharmaceuticals), which consists of 2 L of PEG-based laxative with ascorbic acid (100 g PEG 3350, 1.015 g potassium chloride, 5.9 g sodium ascorbate, 2.691 g sodium chloride, 7.5 g sodium sulfate anhydrous, and 4.7 g ascorbic acid), and water the day before colonoscopy at 7 pm, followed by 1000 mL of water at 10 pm. All bowel preparation methods included 10 mg bisacodyl tablets that were to be ingested the day before colonoscopy.

We performed colonoscopy using a colonoscope (Q260AL, Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), recording the location and size of all polypoid and sessile lesions. All polyps or cancers removed endoscopically or surgically were fixed in formaldehyde and sent to the pathologic laboratory for routine histologic examination. The histological evaluation was conducted in accordance with the World Health Organization criteria. All of the endoscopic examinations were performed by experienced endoscopists.

Bowel preparation quality was assessed by the performing endoscopist using the Aronchick scale [excellent (small volume of clear liquid or >95% of the surface seen), good (large volume of clear liquid covering 5–25% of the surface, but >90% of the surface seen), fair (some semisolid stool that could be suctioned or washed away but >90% of the surface seen), poor (semisolid stool that could not be suctioned or washed away and <90% of the surface seen), and inadequate (repeat preparation needed)].15 In this study, bowel preparation quality was categorized as satisfactory for excellent to good bowel preparation or unsatisfactory for fair to inadequate bowel preparation.

Continuous variables are expressed as means±standard deviations and categorical variables as numbers (%). In univariate analyses, the satisfactory bowel preparation group and unsatisfactory bowel preparation groups were compared using Student's t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. In multivariate analysis, binomial logistic regression analysis was used to analyze factors associated with unsatisfactory bowel preparation. Results were considered to be statistically significant if the p value was <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

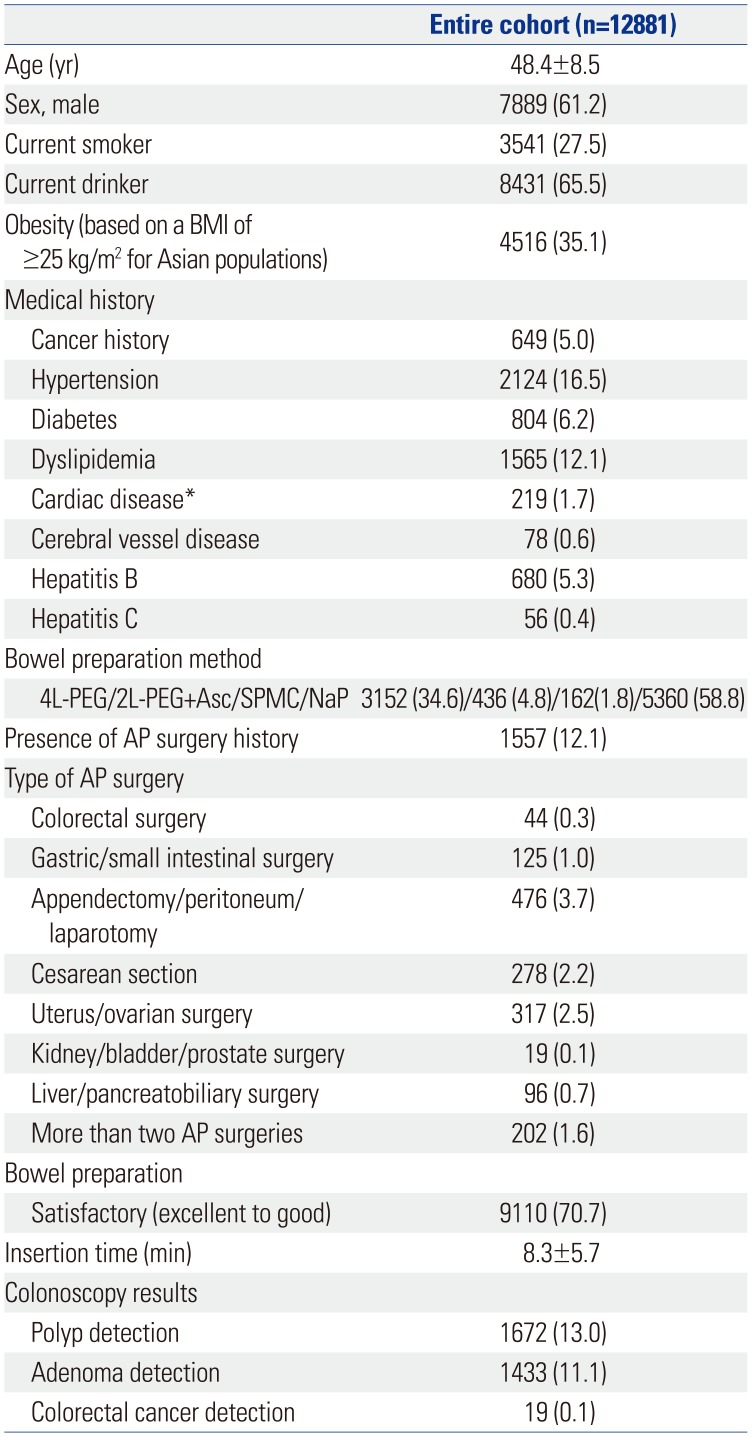

The baseline characteristics of the 12881 participants are described in Table 1. Their mean age was 48.4±8.5 years, and 61.2% were men. Further, 27.5% were current smokers, and 35.1% had obesity [body mass index (BMI) of ≥25 kg/m2 for Asian populations]. Eight hundred and four (6.2%) participants had diabetes, and 649 (5.0%) had a history of cancer. Bowel preparation was performed using NaP, 4L-PEG, 2L-PEG+Asc, and SPMC in 58.8, 34.6, 4.8, and 1.8% of the patients, respectively.

A total of 1557 (12.1%) participants had a history of AP surgery. The type of AP surgery was colorectal surgery (44 participants), gastric/small intestinal surgery (125 participants), appendectomy/peritoneum/laparotomy (476 participants), cesarean section (278 participants), uterus/ovarian surgery (317 participants), kidney/bladder/prostate surgery (19 participants), and liver/pancreatobiliary surgery (96 participants). In addition, 202 participants underwent more than two AP surgeries (Table 1).

Colonoscopy revealed satisfactory bowel preparation in 70.7%. The mean colonoscopy insertion time was 8.3±5.7 minutes. The adenoma detection rate was 11.1%, and the cancer detection rate was 0.1% (Table 1).

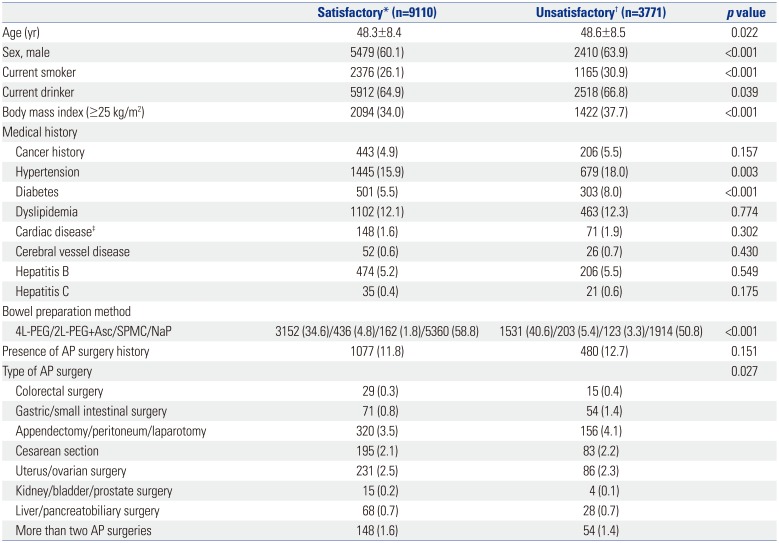

The included participants were divided into two groups based on bowel preparation quality (satisfactory and unsatisfactory). In the univariate analysis, old age (p=0.022), male sex (p<0.001), current smoking (p<0.001), current drinking (p=0.039), obesity (p<0.001), hypertension (p=0.003), diabetes (p<0.001), bowel preparation method (p<0.001), and type of AP surgery (p=0.027) were associated with unsatisfactory bowel preparation (Table 2).

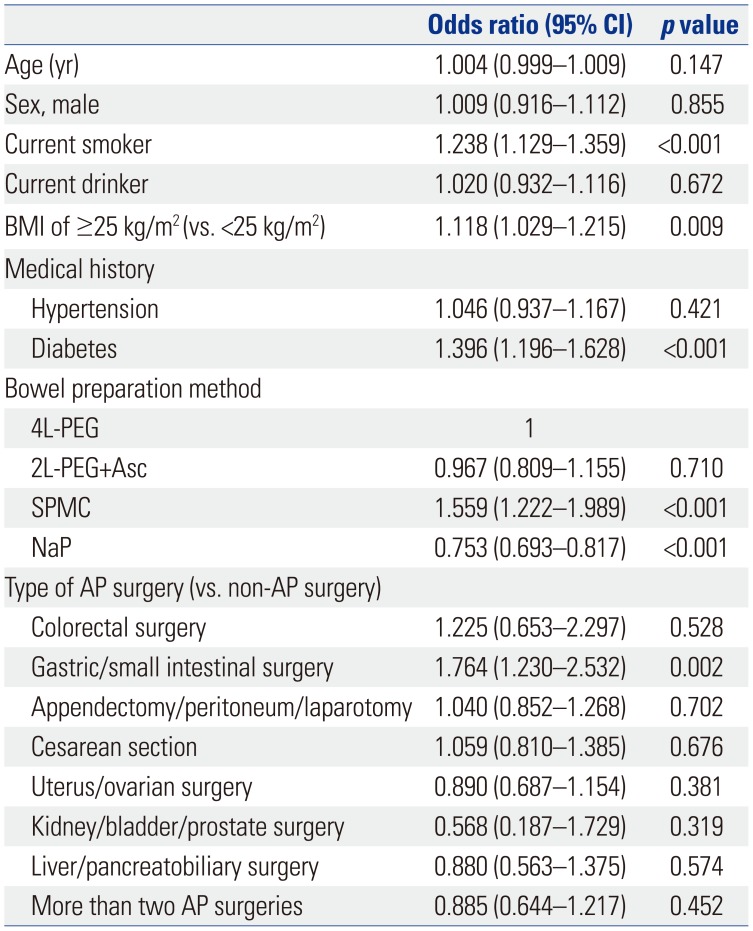

To analyze the factors associated with unsatisfactory bowel preparation, a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, current smoking status, current drinking status, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, bowel preparation method, and type of AP surgery was performed. Unsatisfactory bowel preparation was related to current smoking [odds ratio (OR)=1.238, 95% confience interval (CI)=1.129–1.359, p<0.001], obesity (OR=1.118, 95% CI=1.029–1.215, p=0.009), diabetes (OR=1.396, 95% CI=1.196–1.628, p<0.001), SPMC administration (OR=1.559, 95% CI=1.222–1.989, p<0.001), and gastric/small intestinal surgery (OR=1.764, 95% CI=1.230–2.532, p=0.002). In contrast, NaP administration was related to satisfactory bowel preparation (OR=0.753, 95% CI=0.693–0.817, p<0.001) (Table 3).

The present study demonstrated that gastric/small intestinal surgery is a potential risk factor for poor bowel preparation. The reason for poor bowel preparation quality in patients with a history of bowel resection is unclear. However, there are some possible explanations. First, patients experience altered bowel motility after bowel resection. Second, adhesions can develop after laparotomy as a consequence of the inflammatory response to tissue injury with subsequent healing, and intraabdominal adhesion can cause fixation of the flexible intestine, which may lead to retention of fecal material regionally. Nevertheless, the suggested mechanism for poor bowel preparation in patients with a history of bowel resection is a hypothesis and needs to be proven by additional studies.16 Among the 125 participants who had a prior gastric/small intestinal surgery in this study, 123 underwent gastrectomy mainly due to gastric cancer. Importantly, the incidence of colonic neoplastic lesions in the patients with gastric cancer is higher than that in the general population.171819 Therefore, high-quality colonoscopy is mandatory for these patients.

Meanwhile, however, unlike other intestinal surgery, prior colorectal surgery did not affect bowel preparation quality in this study. In contrast, similar with other bowel resections, prior colorectal surgery was also a risk factor for poor bowel preparation in previous studies.101113 This is probably because the participants with a history of colorectal surgery in the National Cancer Center had previously undergone multiple colonoscopies because of a CRC history. Therefore, several experiences of bowel preparation and the recognition of its importance could affect a successful bowel preparation.

Obesity and diabetes are well-known risk factors for poor bowel preparation in previous studies.20 Further, it is known that the degree of bowel preparation may vary depending on the agents and methods of bowel preparation used.2122232425 Although there is insufficient evidence showing current smoking as a risk factor for poor bowel preparation, a previous study showed the same results with this study.26 The reasons why current smokers were more likely to present with a poorer preparation quality remain speculative. These individuals might have a poorer tolerability to the regimen or failed to follow the preparation schedule completely owing to the relatively lower health consciousness.

A particular strength of this study is its large-scale data compared with those of previous studies. Moreover, colonoscopies were performed by well-trained endoscopists. In addition, numerous patients with a prior abdominal surgery were included because the study was conducted at the National Cancer Center.

Despite the insights provided by the present study, it has some limitations. First, bowel preparation was not conducted using the split method. Second, NaP, which is not used currently owing to safety concerns, was included. Third, we did not use the Boston Bowel Preparation scale, which is the most thoroughly validated scale. Lastly, because of the retrospective study design, some factors that could affect bowel preparation quality, such as completeness of the preparation schedule, compliance rate of low-residual diet, or water intake, could not be investigated. Diet restriction and completeness of the purgatives are crucial factors of a satisfactory bowel preparation.27282930

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that gastric/small intestinal surgery is a potential risk factor for poor bowel preparation. Further research on patients with a history of gastric/small intestinal surgery is mandatory to determine the appropriate methods for an adequate bowel preparation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grants (NCC-1810090, NCC-1610250 and NCC-1810060) from the National Cancer Center, Korea.

References

1. Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:1298–1306. PMID: 24693890.

2. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Liao X, Qian ZR, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:1095–1105. PMID: 24047059.

3. Citarda F, Tomaselli G, Capocaccia R, Barcherini S, Crespi M. Italian Multicentre Study Group. Efficacy in standard clinical practice of colonoscopic polypectomy in reducing colorectal cancer incidence. Gut. 2001; 48:812–815. PMID: 11358901.

4. Rex DK, Johnson DA, Lieberman DA, Burt RW, Sonnenberg A. Colorectal cancer prevention 2000: screening recommendations of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000; 95:868–877. PMID: 10763931.

5. Lindsay DC, Freeman JG, Cobden I, Record CO. Should colonoscopy be the first investigation for colonic disease? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988; 296:167–169.

6. Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 61:378–384. PMID: 15758907.

7. Akere A, Otegbayo JA. Complete colonoscopy: impact of patients' demographics and anthropometry on caecal intubation time. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016; 3:e000076.

8. Anderson JC, Messina CR, Cohn W, Gottfried E, Ingber S, Bernstein G, et al. Factors predictive of difficult colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001; 54:558–562. PMID: 11677470.

9. Church JM. Complete colonoscopy: how often? And if not, why not? Am J Gastroenterol. 1994; 89:556–560. PMID: 8147359.

10. Lim SW, Seo YW, Sinn DH, Kim JY, Chang DK, Kim JJ, et al. Impact of previous gastric or colonic resection on polyethylene glycol bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2012; 26:1554–1559. PMID: 22170320.

11. Hassan C, Fuccio L, Bruno M, Pagano N, Spada C, Carrara S, et al. A predictive model identifies patients most likely to have inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 10:501–506. PMID: 22239959.

12. Nguyen DL, Wieland M. Risk factors predictive of poor quality preparation during average risk colonoscopy screening: the importance of health literacy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010; 19:369–372. PMID: 21188326.

13. Chung YW, Han DS, Park KH, Kim KO, Park CH, Hahn T, et al. Patient factors predictive of inadequate bowel preparation using polyethylene glycol: a prospective study in Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009; 43:448–452. PMID: 18978506.

14. Kim J. Cancer screenee cohort study of the National Cancer Center in South Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2014; 36:e2014013. PMID: 25119453.

15. Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, Dufrayne F, Bergman G. Validation of an instrument to assess colon cleansing [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999; 94:2667.

16. Menzies D, Ellis H. Intestinal obstruction from adhesions--how big is the problem? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990; 72:60–63. PMID: 2301905.

17. Chung HH, Kim KO, Lee SH, Jang BI, Kim TN. Frequency and risk factors of colorectal adenoma in patients with early gastric cancer. Intern Med J. 2017; 47:1184–1189. PMID: 28675538.

18. Joo MK, Park JJ, Lee WW, Lee BJ, Hwang JK, Kim SH, et al. Differences in the prevalence of colorectal polyps in patients undergoing endoscopic removal of gastric adenoma or early gastric cancer and in healthy individuals. Endoscopy. 2010; 42:114–120. PMID: 20140828.

19. Yang MH, Son HJ, Lee JH, Kim MH, Kim JY, Kim YH, et al. Do we need colonoscopy in patients with gastric adenomas? The risk of colorectal adenoma in patients with gastric adenomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 71:774–781. PMID: 20363417.

20. Borg BB, Gupta NK, Zuckerman GR, Banerjee B, Gyawali CP. Impact of obesity on bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 7:670–675. PMID: 19245852.

21. Kwon JE, Lee JW, Im JP, Kim JW, Kim SH, Koh SJ, et al. Comparable efficacy of a 1-L PEG and ascorbic acid solution administered with bisacodyl versus a 2-L PEG and ascorbic acid solution for colonoscopy preparation: a prospective, randomized and investigator-blinded trial. PLoS One. 2016; 11:e0162051. PMID: 27588943.

22. Zorzi M, Valiante F, Germanà B, Baldassarre G, Coria B, Rinaldi M, et al. Comparison between different colon cleansing products for screening colonoscopy. A noninferiority trial in population-based screening programs in Italy. Endoscopy. 2016; 48:223–231. PMID: 26760605.

23. Gimeno-García AZ, Hernandez G, Aldea A, Nicolás-Pérez D, Jiménez A, Carrillo M, et al. Comparison of two intensive bowel cleansing regimens in patients with previous poor bowel preparation: a randomized controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017; 112:951–958. PMID: 28291237.

24. Cheng J, Tao K, Shuai X, Gao J. Sodium phosphate versus polyethylene glycol for colonoscopy bowel preparation: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2016; 30:4033–4041. PMID: 26679172.

25. van Lieshout I, Munsterman ID, Eskes AM, Maaskant JM, van der Hulst R. Systematic review and meta-analysis: sodium picosulphate with magnesium citrate as bowel preparation for colonoscopy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017; 5:917–943.

26. Wong MC, Ching JY, Chan VC, Lam TY, Luk AK, Tang RS, et al. Determinants of bowel preparation quality and its association with adenoma detection: a prospective colonoscopy study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95:e2251. PMID: 26765402.

27. Fang J, Fu HY, Ma D, Wang D, Liu YP, Wang YF, et al. Constipation, fiber intake and non-compliance contribute to inadequate colonoscopy bowel preparation: a prospective cohort study. J Dig Dis. 2016; 17:458–463. PMID: 27356275.

28. Guo X, Yang Z, Zhao L, Leung F, Luo H, Kang X, et al. Enhanced instructions improve the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017; 85:90–97. PMID: 27189659.

29. Liu X, Luo H, Zhang L, Leung FW, Liu Z, Wang X, et al. Telephone-based re-education on the day before colonoscopy improves the quality of bowel preparation and the polyp detection rate: a prospective, colonoscopist-blinded, randomised, controlled study. Gut. 2014; 63:125–130. PMID: 23503044.

30. Wu KL, Rayner CK, Chuah SK, Chiu KW, Lu CC, Chiu YC. Impact of low-residue diet on bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011; 54:107–112. PMID: 21160321.

Table 1

Baseline Characteristics

Table 2

Factors Associated with Bowel Preparation Quality

Table 3

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Unsatisfactory Bowel Preparation

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download