Abstract

Pelvic reconstruction after sacral resection is challenging in terms of anatomical complexity, excessive loadbearing, and wide defects. Nevertheless, the technological development of 3D-printed implants enables us to overcome these difficulties. Here, we present a case of sacral osteosarcoma surgically treated with hemisacrectomy and sacral reconstruction using a 3D-printed implant. The implant was printed as a customized titanium prosthesis from a 3D real-sized reconstruction of a patient's CT images. It consisted mostly of a porous mesh and incorporated a dense strut. After 3-months of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the patient underwent hemisacretomy with preservation of contralateral sacral nerves. The implant was anatomically installed on the defect and fixed with a screw-rod system up to the level of L3. Postoperative pain was significantly low and the patient recovered sufficiently to walk as early as 2 weeks postoperatively. The patient showed left-side foot drop only, without loss of sphincter function. In 1-year follow-up CT, excellent bony fusion was noticed. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a case of hemisacral reconstruction using a custom-made 3D-printed implant. We believe that this technique can be applied to spinal reconstructions after a partial or complete spondylectomy in a wide variety of spinal diseases.

Reconstruction after sacral resection is challenging in terms of anatomical complexity, excessive loading, and wide defects.123 It is well documented that surgical resection increases survival rate in patients with sacral osteosarcoma.4 Although en bloc resection is the most common type of sacral resection used, surgical morbidity and survival benefits should be considered carefully. While total sacrectomy will induce neurogenic bladder dysfunction and fecal incontinence, gait disturbance, and sexual dysfunction, hemisacrectomy can preserve the contralateral sacral nerves and may prevent or lessen these complications.

In general, human bone or titanium mesh with a pedicle screw-rod system has been used to restore biomechanical stability of the sacroiliac complex. However, graft bone or titanium mesh may not be appropriate for the normal sacrum because of its different shape, narrow contact surface, and limited 3D configuration. To overcome these limitations, we used 3D-printing technology and successfully grafted a 3D-printed implant to a patient with sacral osteosarcoma. To our best knowledge, anatomical reconstruction of the sacrum using 3D-printing technology has not previously been reported.

A 16-year-old girl presented with left buttock and leg pain for 3 months. There was no neurological dysfunction. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a lobulated mass (3.4×4.7×5 cm, roughly 362 cm3) with peripheral enhancement at the left sacrum mainly at the level of S1 and S2 (Fig. 1A). Fluoroscope-guided bone biopsy was performed preoperatively. Histological examination revealed chondroblastic osteosarcoma. Treatment plan was decided in a multidisciplinary tumor board consisting of a pediatric oncologist, neurosurgeon, orthopedic surgeon, and radiation oncologist. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin, adriamycin, and methotrexate was given preoperatively for 3 months. Follow-up pelvic MRI demonstrated a moderate reduction (32%) of the mass (4.4×3.2×4.2 cm, roughly 248 cm3) with a significant reduction of the peripheral extension (Fig. 1B). The extent of previously noted enhancement at the left iliacus muscle was also decreased. During the period of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, implant design and surgical planning were conducted.

The pelvic MRI was exported in a digital imaging and communications in medicine format to the 3D software (Mimics; Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). The whole process is illustrated in Fig. 2. A customized volume was generated as stereolithography format, which is a standard form of manufacturing. The process was performed in a stepwise manner. The sacrum was segmented by threshold using a function that includes only those pixels of the image with a value higher than or equal to the threshold value (segmentation). A 3D rendering of the sacrum was reconstructed with an automatic function (3D reconstruction). A customized implant was designed using other software (3-matic; Materialise). The sacral implant was designed as a patient-specific structure mostly identical to the anatomical structure. Several rapid prototype (RP) models were printed using a conventional 3D-printer for review and correction. With the final MRI and RP models, modification was made interactively. Then, the internal architecture was designed using other software (Magics; Materialise).

A metal printer (Arcam-EBM A1; ArcamAB, Mölndal, Sweden) system was used to print the implant. The material was Ti-6Al-4V extra-low interstitial medical grade powder. In this system, the focused electron beam is rastered over each successive layer of powder, which is gravity-fed from powder containers and raked into successive layers roughly 50 µm thick. The building component is lowered on the build table with the completion of each successive layer. Each newly raked powder layer is initially rastered by the beam with approximately 11 passes at a beam current of approximately 35 mA to preheat each layer to approximately 600℃. This layer preheat is normally followed by a 4 mA beam current. The melt scan is driven by a 3D computer-assisted design program and melts only selected layer areas, which add metal to the build. The printed implant was inspected extensively and modified several times. The final implant was obtained and delivered to the operating room (Fig. 3).

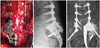

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for operation and publication. After general endotracheal anesthesia, a unilateral retroperitoneal approach was made from the left side. The goal of our anterior approach was dissection of the ventral portion of L5 and the sacrum from the visceral and vascular structures. Anterior sacroiliac ligament was released and the left S1, S2, S3, and S4 nerve roots were ligated and cut. To ensure the dissection margin, dry tapes were placed around the lesion site. The patient's position was subsequently changed to prone on a surgical frame. A midline vertical incision was made from L2 to the level of the coccyx, and the paraspinal muscles were dissected. After full exposure of the dorsal sacrum, we performed laminectomy and cut the proximal portion of the left S1, S2, S3, and S4 nerve roots. Left S1 and S2 nerve roots were involved in tumor. We needed a space that the implant could be inserted all at once. Li, et al.5 reported that unilateral sacral nerve roots resection could preserve normal residual function. Thus, resection of left sacral nerve roots was inevitable. We cut the posterior sacroiliac ligamentous structures, and then split the sacrum on its exact midline. En bloc resection of the left hemisacrum was achieved with cutting the distal portion of the left S1, S2, S3, and S4 nerve roots (Fig. 3). Pedicle screws were inserted bilaterally from L3 to the iliac. One screw was inserted on a 3D-printed construct at the level of S1. The sacral screws and lumbo-iliac screws were strongly attached with rods and domino connectors. At the midline, the implant was further fixed to the right sacrum with metallic cables (Atlas cable; Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA) through the sacral pore and to the iliac bone (Fig. 4A).

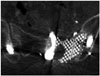

The patient was advised for 2 weeks bed rest. We encouraged the patient to change her position often to prevent surgical wound sores. The patient was able to walk after 2 weeks. Neurogenic bladder or bowel dysfunction was absent. Two weeks after surgery, the foley catheter was removed. Five days later, the patient did not have any bladder and bowel symptoms. Therefore, we did not need additional examination for bladder and bowel functions. However, a left foot drop and neuropathic pain on left leg occurred postoperatively because of resection of the left S1 nerve root. We applied an ankle-stabilizing orthosis and performed rehabilitation. Gabapentin was administered in order to control neuropathic pain. Visual Analog Scale (VAS) socre of left leg was eight immediately after the surgery. VAS score was gradually reduced to three at a year after the surgery. The pediatric oncologist had performed three cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy up to 12 months after the surgery. Complications were not observed until a year after the surgery. In our patient, plain radiographs of the lumbosacral spine showing the anterior-posterior and lateral views at 12 months postoperatively demonstrate that instrumentation has been well maintained (Fig. 4B and C). Also, bone ingrowth into the titanium porous structure and bone fusion between medial side of right sacrum and high-density aspect of the implant were confirmed by computed tomography (Fig. 5).

En bloc resection with a wide margin is the standard treatment of osteosarcoma.6 Sacral osteosarcoma is not an exception. A wide variety of techniques have been suggested in pelvic reconstruction after sacrectomy.78 Although pelvic reconstruction is challenging because of anatomical complexity and excessive weight bearing, optimal methods have not yet been developed because of the rarity of sacral lesions. Because there are no ready-made implants, various grafts have been used despite donor site complications.9101112 Subsequent screw fixation or its variants have been added to reinforce the constructs.13141516 While surgeons strive to build rigid constructs, dead space inevitably occurs at the resected region. Therefore, plastic reconstructions overlying spinal instrumentation may be additionally required.17 Both loosely fitted constructs and graft harvesting may induce desperate pain and significantly limits a patient's activities of daily living.

The present case demonstrated how we applied 3D-printing technologies to pelvic reconstruction in the case of aggressive sacral tumor. A customized implant, which fitted the patient's anatomy, minimizing dead space and eliminating additional reconstruction, was used. In conventional pelvic reconstructions, more than two grafts have usually been assembled to geometrically different cages and screws over a significant period of time. Our 3D-printed implant incorporated all necessary structures in itself and lessened the number of surgical stages. This resulted in the shift of a significant amount of the construction process from intraoperative to preoperative time. By minimizing the gap between the implant and bone and maximizing the contact area, the tightly fitting implant can better maintain stability and lessen postoperative pain. Our patient experienced a slight postoperative pain and walked without assistance as early as 2 weeks postoperatively.

Considering the long-term results of reconstruction surgeries, rigid fusion between bone and implants has always been a major issue. The 1-year follow-up results of the present case showed that excellent bony union can be achieved on both the densely structured strut surface and loosely structured porous mesh. To accelerate bony fusion on the surface of the implant, we made the strut surface rugged and used porous mesh. Both rugged surface and porous structure have previously been reported as osteointegrative.181920

The present case and its 1-year follow-up results demonstrated that 3D-printing technologies might ultimately change our surgery on the sacrum and its surrounding structures. In addition to the surgery itself, the preoperative design process significantly increased our stereotypic understanding of the patient's anatomy and accelerated surgical decision-making.

There are potential pitfalls of 3D-printed implants. Distinct from conventional implants, the strength of 3D-printed implants may not be guaranteed. Research on this issue is ongoing and international standardization process will produce better results. Individualized investigation using a finite element analysis method may be adopted. Intraoperative modification is limited. Although minimal changes may be possible using drill grinding or cement augmentation, major modification is impossible because of its significant printing and manufacturing time and limited extension capabilities. Long-term results for 3D-printed implants have seldom been reported.

Despite these limitations, 3D-printed implants are expected to be applied extensively because of their clear advantages. Not only 3D-printing technology in itself, but the technology also will be used to measure, understand, and educate surgical anatomy preoperatively. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a case of hemisacral reconstruction using a custom-made 3D-printed implant. We believe that this technique can be applied to spinal reconstructions after partial or complete spondylectomy in a wide variety of spinal diseases.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Preoperative Gd-enhanced T1-weighted pelvic MRI showing a mass with peripheral enhancement at the left side of the sacrum (arrowheads) with soft tissue invasion (asterisk). (B) After three cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for 3 months, the volume of tumor mass (arrowheads) and the extent of extraosseous invasion (asterisk) decreased significantly.

Fig. 2

Illustration of 3D-implant design process. A customized implant was designed using 3D software (Mimics, 3-matic, Magics). The design process (dotted box) was performed during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The design was interactively corrected reflecting the final pelvic MRI and RP models before final printing. RP, rapid prototype.

Fig. 3

(A) Custom-made 3D-printed hemisacral construct with a specific porous titanium structure. The screw hole and contact surfaces were made with high-density structure. (B) The left sacrum was excised with en bloc resection. The shape and size of the implant were the same as the resected mass.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF 2011-0010067) and the Industrial R&D program of MOTIE/KEIT (10052732).

References

1. Zileli M, Hoscoskun C, Brastianos P, Sabah D. Surgical treatment of primary sacral tumors: complications associated with sacrectomy. Neurosurg Focus. 2003; 15:E9.

2. Fourney DR, Rhines LD, Hentschel SJ, Skibber JM, Wolinsky JP, Weber KL, et al. En bloc resection of primary sacral tumors: classification of surgical approaches and outcome. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005; 3:111–122.

3. Zoccali C, Skoch J, Patel A, Walter CM, Maykowski P, Baaj AA. The surgical neurovascular anatomy relating to partial and complete sacral and sacroiliac resections: a cadaveric, anatomic study. Eur Spine J. 2015; 24:1109–1113.

4. Mukherjee D, Chaichana KL, Parker SL, Gokaslan ZL, McGirt MJ. Association of surgical resection and survival in patients with malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Eur Spine J. 2013; 22:1375–1382.

5. Li D, Guo W, Tang X, Yang R, Tang S, Qu H, et al. Preservation of the contralateral sacral nerves during hemisacrectomy for sacral malignancies. Eur Spine J. 2014; 23:1933–1939.

6. Ozturk AK, Gokaslan ZL, Wolinsky JP. Surgical treatment of sarcomas of the spine. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2014; 15:482–492.

7. Yu B, Zheng Z, Zhuang X, Chen H, Xie D, Luk KD, et al. Biomechanical effects of transverse partial sacrectomy on the sacroiliac joints: an in vitro human cadaveric investigation of the borderline of sacroiliac joint instability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009; 34:1370–1375.

8. Hugate RR Jr, Dickey ID, Phimolsarnti R, Yaszemski MJ, Sim FH. Mechanical effects of partial sacrectomy: when is reconstruction necessary? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006; 450:82–88.

9. McKnight AJ, Lewis VO, Rhines LD, Hanasono MM. Femur-fibula-fillet of leg chimeric free flap for sacral-pelvic reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013; 66:1784–1787.

10. Wang J, Tang Q, Xie X, Yin J, Zhao Z, Li Z, et al. Iliosacral resections of pelvic malignant tumors and reconstruction with nonvascular bilateral fibular autografts. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012; 19:4043–4051.

11. Gillis CC, Street JT, Boyd MC, Fisher CG. Pelvic reconstruction after subtotal sacrectomy for sacral chondrosarcoma using cadaveric and vascularized fibula autograft: technical note. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014; 21:623–627.

12. Mendel E, Mayerson JL, Nathoo N, Edgar RL, Schmidt C, Miller MJ. Reconstruction of the pelvis and lumbar-pelvic junction using 2 vascularized autologous bone grafts after en bloc resection for an iliosacral chondrosarcoma. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011; 15:168–173.

13. Wuisman P, Lieshout O, van Dijk M, van Diest P. Reconstruction after total en bloc sacrectomy for osteosarcoma using a custom-made prosthesis: a technical note. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001; 26:431–439.

14. Gokaslan ZL, Romsdahl MM, Kroll SS, Walsh GL, Gillis TA, Wildrick DM, et al. Total sacrectomy and Galveston L-rod reconstruction for malignant neoplasms. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1997; 87:781–787.

15. Newman CB, Keshavarzi S, Aryan HE. En bloc sacrectomy and reconstruction: technique modification for pelvic fixation. Surg Neurol. 2009; 72:752–756.

16. Doita M, Harada T, Iguchi T, Sumi M, Sha H, Yoshiya S, et al. Total sacrectomy and reconstruction for sacral tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003; 28:E296–E301.

17. Kim JE, Pang J, Christensen JM, Coon D, Zadnik PL, Wolinsky JP, et al. Soft-tissue reconstruction after total en bloc sacrectomy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015; 22:571–581.

18. Girasole G, Muro G, Mintz A, Chertoff J. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion rates in patients using a novel titanium implant and demineralized cancellous allograft bone sponge. Int J Spine Surg. 2013; 7:e95–e100.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download