Abstract

We report a case of bronchiolitis obliterans associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. A 59-year-old man presented with respiratory distress that gradually worsened over 3 months. He had been diagnosed with Stevens-Johnson syndrome 3 months before admission. He had no history of previous airway disease. On physical examination, expiratory breathing sounds were not audible, and a chest X-ray revealed a hyperinflated lung. A pulmonary function test indicated a severe obstructive pattern. Computed tomography scans of inspiratory and expiratory phases of respiration showed oligemia and air trapping, and both were more prominent on expiration view than on inspiration view. The pathogenesis of bronchiolitis obliterans associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome is largely unknown.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a life-threatening drug-induced reaction.1 It is an erythema multiforme of the skin and mucosa, and is characterized by a polymorphous vesicular and bullous eruption, with systemic manifestations of variable severity. Bronchopulmonary complications are rare.2 Bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) is characterized by bronchiectasis of the large airways, luminal obstruction and obliterans of the small airways. It is known to be caused by infection (such as adenovirus and Mycoplasma pneumoniae), but rarely caused by SJS.3 Until now, only four adult cases of BO associated with SJS have been reported. Among the four cases, two were diagnosed ante-mortem.

A 59-year-old man previously diagnosed with SJS was admitted to Asan Medical Center with dyspnea and worsening skin lesions in April 2013. About 10 months before admission, steroid treatment was initiated to treat a recurrent tongue ulcer, and 6 months before admission the patient was prescribed prednisolone and colchicine for suspected Behcet's disease. The patient was prescribed several unidentified medications at different clinics. Three months before admission, he developed swelling of his hands, skin rash, and scaled skin lesion on both hands and feet. He was admitted to an another hospital and diagnosed with SJS. Prednisolone and anti-histamine were continued to treat the skin conditions.

Three weeks before admission, while the skin lesions showed improvement, the patient complained of increased dyspnea. Prior to admission, he could walk only 100-meters. A pulmonary function test (PFT) showed severe obstructive patterns: forced vital capacity (FVC) of 3.4 L (69% of predicted capacity), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 1.01 L (27% of predicted volume), FEV1/FVC of 30%, forced expiratory flow (FEF) 25-75% of 0.32 L/s (10% of predicted flow), and FEF 25-75%/FVC ratio of 0.094. An arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.383, PCO2 of 41.9 mm Hg, PO2 of 77.4 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 95.1% under room air. Tiotropium-bromide and salmeterol/fluticasone were administered, followed by a slight improvement in his dyspnea.

One week later, the patient's skin lesions deteriorated rapidly after the patient took other medications, including an H2 antagonist prescribed from a local clinic. At this time, he visited the emergency department of our hospital. The patient had no history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. He had a 15-pack-year history of tobacco smoking but had stopped 10 years earlier. He did not consume alcohol.

On admission, the patient's blood pressure was 138/101 mm Hg, pulse 100 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 98% under room air. There were bullas and multiple skin eruptions covering approximately 20% of his skin surface involving the oral mucosa, eyes, and ears. H2 antagonist was commonly prescribed previously at different clinics, and it was also prescribed 1 week earlier when his skin lesions deteriorated rapidly, indicating H2 antagonist as the cause of his SJS. Systemic steroid therapy and skin dressing were initiated immediately. Two weeks after admission, despite improvement of the skin lesions, his dyspnea worsened progressively, and he was finally intubated and moved to the intensive care unit (ICU).

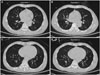

Compared to 6 weeks prior (Fig. 1A), a chest X-ray on admission (Fig. 1B) revealed severe hyperinflation in both lung fields, and there was no audible expiratory breathing sound in either lung fields. Bronchoscopy revealed no endobronchial lesions. We suspected the possibility of BO, therefore, performed inspiratory-expiratory CT. CT scanning revealed mild bronchial dilatation, oligemia, and air trapping lesions on the left upper lobe anterior segment, the right middle lobe medial segment, the right lower lobe superior segment, both the lower lobe basal portions, and most of the left lower lobe (Fig. 2A and C). These findings were prominent on expiration view (Fig. 2B and D). Consequently, two weeks after admission when he moved to ICU, we finally diagnosed the patient with BO following SJS.

The patient underwent tracheostomy and continued on mechanical ventilation. Along with corticosteroid and bronchodilators, roxithromycin was started, but had no effect. The patient's skin lesions improved gradually, however, carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumanii and methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus pneumonia developed. Later in the ICU, pneumothorax also developed. His PaCO2 level increased to around 100 mm Hg despite mechanical ventilation, and he died 6-months after admission due to respiratory failure and secondary pulmonary complications.

In 1995, Yatsunami, et al.4 reported a patient with BO associated with SJS who had been diagnosed without autopsy. They proposed clinical diagnostic criteria for BO after SJS: dyspnea and wheezing that are not alleviated by bronchodilators or corticosteroids, severe obstructive pulmonary dysfunction, and obstructive changes in relatively central bronchi, which are confirmed by bronchography and bronchos-copic findings. A few cases of BO after SJS with a histologic confirmation have since been reported.5,7,8 In the autopsied lungs of patients with BO after SJS, Sugino, et al.7 noted macroscopically extensive occlusion of the bronchi at the 4th or 5th branches, more distal bronchi than the segmental bronchus. The occlusive lesions were sporadically and intermittently located from the small bronchi to the membranous bronchioli.

Our patient presented with dyspnea 3 months after the onset of skin lesions. Expiratory breathing sounds were not audible, and chest X-ray showed hyperinflatedlung. In addition, PFT revealed a severe obstructive pattern. He underwent inspiratory-expiratory chest CT instead of bronchography and bronchoscopy, which revealed mild bronchial dilatation, oligemia, and air trapping lesions, suggesting BO. Lung biopsy could give us more information to diagnose BO, but was not performed in the patient because of poor condition. BO was a clinical diagnosis, and pathologic confirmation is not mandatory for diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of BO after SJS remains unclear. Sugino, et al.7 suggested that BO maybe a consequence of bronchiolar epithelial and mucosal damage due to immune complex deposition in SJS. These injuries may initiate necrosis and subsequent exudation of the fibrin and inflammatory cells of the airways. Obliteration of bronchiolar lumens can then develop due to fibrous granulation tissue.7 In an another case, autopsy findings suggested initial epithelial detachment in the airways, which may lead to exudation and granulation tissue formation in the airway lumen. Yatsunami, et al.4 suggested overproliferation of fibrous granulation tissue as the cause of this condition. In view of these explanations, mild cases may also develop, but the prevalence of such cases is not known.

No effective therapy exists for patients with BO after SJS. In our case, steroids were administered to modify the fibrotic response of the disease, but were not effective. In addition, bronchodilators were used for symptomatic relief and macrolide as anti-inflammatory drugs.9 Despite the treatment with steroids, a bronchodilator, and roxithromycin therapy, the airway obstruction of the patient progressed and he died 6 months after admission. In four cases reported previously, only one patient survived.4,5,7,10

In conclusion, BO can develop in patients with SJS. Presently, the pathogenesis of this condition is unknown, and effective treatment is not available. It is important to consider the possibility of this devastating complication in patients with SJS.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Chest radiograph 6 weeks prior to admission showing normal findings. Note that the dome of the right diaphragm is at the level of the 10th rib posterior arc. (B) Chest radiograph showing hyperinflated lung without significant opacities. Note that the dome of the right diaphragm is at the level of the 11th rib posterior arc.

Fig. 2

Inspiratory and expiratory CT scans of 59-year-old male patient with bronchiolitis obliterans associated with SJS. (A) Inspiratory CT scan revealing a partially low attenuated lung lesion, collapsed vascular structure (oligemia and air trapping), and mild bronchial dilatation. (B) Expiratory CT scan revealing more prominent findings, such as shifted interlobular fissure, lower attenuated lung lesion, collapsed vascular structure, and obstructed bronchus. (C and D) Another set of inspiratory and expiratory CT images of the patient. SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

References

1. Roujeau JC, Kelly JP, Naldi L, Rzany B, Stern RS, Anderson T, et al. Medication use and the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. N Engl J Med. 1995; 333:1600–1607.

2. Stitt VJ. Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a review of the literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 106; 80:104.

3. Kim CK, Kim SW, Kim JS, Koh YY, Cohen AH, Deterding RR, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans in the 1990s in Korea and the United States. Chest. 2001; 120:1101–1106.

4. Yatsunami J, Nakanishi Y, Matsuki H, Wakamatsu K, Takayama K, Kawasaki M, et al. Chronic bronchobronchiolitis obliterans associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Intern Med. 1995; 34:772–775.

5. Tsunoda N, Iwanaga T, Saito T, Kitamura S, Saito K. Rapidly progressive bronchiolitis obliterans associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Chest. 1990; 98:243–245.

6. Date H, Sano Y, Aoe M, Goto K, Tedoriya T, Sano S, et al. Living-donor lobar lung transplantation for bronchiolitis obliterans after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002; 123:389–391.

7. Sugino K, Hebisawa A, Uekusa T, Hatanaka K, Abe H, Homma S. Bronchiolitis obliterans associated with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome: histopathological bronchial reconstruction of the whole lung and immunohistochemical study. Diagn Pathol. 2013; 8:134.

8. Shah AP, Xu H, Sime PJ, Trawick DR. Severe airflow obstruction and eosinophilic lung disease after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2006; 28:1276–1279.

9. Gerhardt SG, McDyer JF, Girgis RE, Conte JV, Yang SC, Orens JB. Maintenance azithromycin therapy for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: results of a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003; 168:121–125.

10. Sugino K, Kimura K, Sano G, Kato N, Takagi K, Tsuchiya K, et al. [An autopsy case of obliterative bronchiolitis associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2006; 44:511–516.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download