Abstract

Cutis verticis gyrata (CVG) is a descriptive term for a scalp condition that is convoluted folds and deep furrows that resemble the surface of the cerebral cortex. It is categorized by the underlying etiology, as primary essential, primary non-essential and secondary. Alopecia areata (AA) is a common, organ specific autoimmune disease, and most AA cases are sporadic. There is clearly a strong genetic component. There is no established relationship between CVG and AA. We report one case which was affected with essential primary CVG and alopecia areata, and suggest a possibility of genetic association between CVG and AA, possibly both being related to mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2).

Cutis verticis gyrata (CVG) is a lesion that influences morphological characteristics of the scalp, in which deep furrows and folds resemble the surface of the brain. Based on its causes, it can be classified into primary and secondary. The primary type can further be classified into essential and nonessential, according to whether other lesions are associated with it.1 The growth, amount, and structure of the hair have been reported to be normal in all the aforementioned reported cases.

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common, organ-specific autoimmune disease with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 1.7%.2 While most cases of AA are sporadic, there is clearly a strong genetic component. Simultaneous occurrence of these two diseases has not yet been reported in the literature. Therefore, we suggest a possibility of genetic association between CVG and AA, possibly both being related to mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2).3

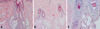

A 28 year old male patient, was committed to the hospital after complaining of a number of folds on his parietalis and occcipitalis, and of a number of alopecic patches all over his scalp. Since 10 years before his hospitalization, he had observed a number of folds from his partietalis to occipitalis, owing to his repeated cushioning and cupping of the lesion thereon, and a number of alopecic patches had appeared all over the scalp since six months before his hospitalization. The folds were not corrected even when pressure was applied on them, and the patient complained of a slight itching sense and tenderness in the affected areas (Fig. 1). In regards with the patient's past and family history, no particular indications were found. Normal results were obtained from the routine blood test, chemical test, urinalysis, endocrine system tests (including the thyroid function and insulin tests), and chest and head X-ray tests. No abnormal findings in the epidermis were obtained either from the biopsy executed in the furrow region at the occipitalis, however, intimal hyperplasia in the piloerector muscle was observed in the dermis, along with the increase of collagen (Fig. 2A). No abnormal findings were obtained from either the biopsy carried out in the fold region at the parietalis, except for a slight increase of collagen at the dermis (Fig. 2B). The scalp biopsy on the vertex fold area with alopecia areata area showed lymphocytic peribulbar infiltration (Fig. 2C). The patient, therefore, was diagnosed as having essential primary CVG associated with alopecic areata. However, our patient refused further evaluation for gene mutation analysis because of its high cost. Furthermore, we did not perform unfortunately any chromosome study, such as FGFR2. The patient is not presently under treatment for CVG, nevertheless, the alopecic areata is being treated with intralesional triamcinolone (10 mg/0.1 cc) injection and a topical agent (Minoxyl 5%®).

In 1953, Polan, Buterworth, and others classified CVG into primary and secondary CVG, according to whether there is a causative disease or a pathological state. In 1984, Garden and Robinson, and others classified those cases that are not associated with abnormal findings as essential primary CVG cases, and those associated with abnormal findings (e.g., cerebral palsy, microcrania, brachycephaly, epilepsy, congenital ocular anomaly) as nonessential primary CVG cases.1,4

The lesion is mostly asymptomatic, and two to twenty folds can occur symmetrically from repeated cushioning and cupping. Their direction is usually from the back to the front or from the front to the back, however, they sometimes run from left to right or from right to left, or sideways. The hair on the affected area grows normally, with a normal amount and structure.5,6 Moreover, no hair damage was observed, in all the aforementioned reported cases, as observed in cases associated with reticular alopecia and normal hair.

CVG can easily be diagnosed; one has to observe only the characteristic morphological aspects of the patient's scalp. However, in order to decide whether there are causative or associated diseases, the patient's past and family history are needed in addition to lab findings, radiologic findings, histologic examination results, etc.

As for the histopathological findings, normal primary findings can be obtained, however, the thickening of the collagen fiber, hyperplasia of the pilar cyst, and sebaceous glads are also observed.7 In our present case, a slight increase of collagen and hyperplasia in the piloerector muscle was observed, while lymphocytic peribulbar infiltration was observed in alopeic areata lesions.

Pathogenesis of CVG is not yet known, nevertheless, some authors suggested an autosomal dominant condition caused by mutation in the FGFR2,3 because CVG is characterized by dermal hypertrophy. FGFR2 gene encodes a transmembrane tyrosine kinase and can function as a mitogenic, angiogenic or inflammatory factor, depending on the cell type and/or the microenvironment.8 It's sequence has considerable homology to binding interleukin 6 (IL-6) promoter.9 Therefore, it is highly likely that IL-6 level is increased in CVG. IL-6 is known to promote B-cell differentiation and to drive immunoglobulin production, and IL-6 production has been implicated in autoimmune disease.10 Therefore, IL-6 may play a key role in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata, because it is also an autoimmune disease.

Futhermore, FGFR2 is located on chromosome 10q22. Most recently, a genome-wide search for linkage in 20 families with AA in the United States and Israel revealed evidence of at least four susceptibility loci on chromosomes 6, 10, 16, and 18,11 raising a possibility that CVG and AA are related to mutation of genes on chromosome 10.

It is NOT certain at present whether these two different disease entities have any correlation or not. However, we suggest that there is the possibility of genetic association between CVG and AA. Such a mechanism may involve mutations in the FGFR2, therefore, further studies on CVG and AA should be continued in order to solve this puzzle.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The skin on the scalp shows parallel vertical folds and furrows. Hair appears multiple bald patches on the scalp.

Fig. 2

(A) The scalp biopsy on the occipital furrow area shows slightly increased dermal collagen and arrector pilar muscle (H&E stain,×20). (B) The scalp biopsy on the vertex fold area shows slightly increased dermal collagen (H&E stain,×20). (C) The scalp biopsy on the vertex fold area with alopecia areata area shows lymphocytic peribulbar infiltration (H&E stain,×40).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A091121).

References

2. Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, Moshell AN, Melton LJ 3rd. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted Country, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995. 70:628–633.

3. Claude SB, Vaishali E. Jeffrey PC, Thomas DH, Anthony JM, Stuart JS, Julie VS, Thomas S, editors. Dermal hypertrophies. Bolognia dermatology. 2008. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier;1502.

4. Synder MC, Johnson PJ, Hollins RR. Congenital primary cutis verticis gyrata. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002. 110:818–821.

5. Schenato LK, Gil T, Carvalho LA, Ricachnevsky N, Sanseverino A, Halpern R. [Essential primary cutis verticis gyrata]. J Pediatr (RiO J). 2002. 78:75–80.

6. Tan O, Ergen D. Primary essential cutis verticis gyrata in an adult female patient: a case report. J Dermatol. 2006. 33:492–495.

7. Larsen F, Birchall N. Cutis verticis gyrata: three cases with different aetiologies that demonstrate the classification system. Australas J Dermatol. 2007. 48:91–94.

8. Meyer KB, Maia AT, O'Reilly M, Teschendorff AE, Chin SF, Caldas C, et al. Allele-specific up-regulation of FGFR2 increases susceptibility to breast cancer. PLoS Biol. 2008. 6:e108.

9. Akira S, Isshiki H, Sugita T, Tanabe O, Kinoshita S, Nishio Y, et al. A nuclear factor for IL-6 expression (NF-IL6) is a member of a C/EBP family. EMBO J. 1990. 9:1897–1906.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download