Abstract

Tailgut cysts (TGCs) are rare congenital cysts that occur in the retrorectal or presacral spaces. Although most tailgut cysts have been reported as benign, there have been at least 9 cases associated with malignant change. We report herein on an unusual case of a 40-year-old woman with a carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-producing adenocarcinoma arising within a TGC who underwent surgical resection and local radiation therapy. Despite the complete resection, metastatic adenocarcinoma developed five months after surgery. CEA-producing adenocarcinoma from a TGC is extremely rare and only two cases, including this case, have been reported in the English medical literature. Besides CEA, the serum levels of CA 19-9 became markedly elevated in this patient. Given that the serum CEA level decreased to the normal range after complete resection of tumor and that the tumor recurrence was associated with a rebound of the CEA serum level, our case shows that serial measurements of serum CEA can be used for treatment planning and for assessing the patient's treatment response for this rare disease.

The tailgut cyst (TGC) is a rare benign cystic lesion located in the retrorectal space, and it is believed that this cyst is derived from the persistent embryologic remnants of the postanal gut.1 These lesions typically present as a presacral mass, and they are frequently misdiagnosed, which may be due in part to the physician's unfamiliarity with this entity.1,2 In a comprehensive review of 53 cases by Hjermstad and Helwig,1 a correct histologic diagnosis was made in only 2 cases. The incidence of malignancy in TGCs is extremely rare; besides our case, only 10 well-documented cases of associated malignancy arising from within a tailgut cyst have been reported in the English literature.2-11 There have only been 6 cases of tailgut cysts, including one case of adenocarcinoma, reported in Korea.11-16 We describe here in this report the clinicopathologic and radiologic features of adenocarcinoma arising within a TGC. Furthermore, we discuss and suggest the possible therapeutic implications of serum CEA and CA 19-9 for this rare disease.

A 40-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital because of a 1 month history of severe perianal pain. Her medical history included a wide excision of presacral cystic masses; this operation was performed in July, 2001, when she presented with abdominal pain. The operative specimen consisted of two well-circumscribed cystic masses that measured 3 cm and 5 cm in diameter, respectively. The cysts were unilocular and contained a yellowish, gelatinous material. Microscopically, the cyst lining consisted of various epithelial cells, mostly squamous epithelia, and the cyst wall displayed disorganized smooth muscle bundles without a neural plexus, thus confirming the diagnosis of tailgut cyst. She had been doing well after her surgery until the start of her aforementioned aggravating symptoms. Before the patient's presentation at our hospital, a percutaneous biopsy through a posterior approach yielded a poorly differenciated carcinoma specimen with focal squamous differentiation. On admission, the physical examination revealed a posterior extrinsic mass compressing the rectum, the stool was negative for blood and there were no other important findings. A barium enema study demonstrated the left-anterior displacement of the posterior wall of the rectum (Fig. 1). T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated an irregular cystic mass measuring 6 cm in diameter within the retrorectal space and it was involving coccygeal bone and right gluteous muscle tendon (Fig. 2A, 2B, 2C). There was no radiological evidence of extrapelvic metastasis and a whole body bone scan revealed increased bone uptake in the coccyx. The laboratory test values were normal except for a remarkable elevation in serum CEA level to 159 ng/mL (normal 0 - 5 ng/mL) and serum CA19 - 9 level to 2270 U/mL (normal 0 - 37 U/mL). The patient underwent enbloc resection of the mass and a Hartmann operation with coccygectomy and partial sacrectomy to the level of S4 through a combined abdominal/sacral approach. Upon gross examination, the specimen measured 10 × 7 × 8 cm; it was an ill-defined mass impinging on the outer wall of rectum, the presacral soft tissue and coccygeal bone. The mass displayed a firm gray-white appearance on sectioning and contained several small, unilocular cysts filled with a yellow gelatinous material (Fig. 3). Microscopic examination revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with infiltrative growth to the surrounding tissue (Fig. 4A). The wall of the cysts consisted of various types of epithelium, including ciliated columnar, columnar and focal cuboidal epithelium; this was consistent with a TGC (Fig. 4B, 4C). The resection margin was negative and the regional lymph nodes were free of carcinoma. After her operation, the patient's postoperative CEA level had returned to normal. The patient underwent radiation therapy after surgery to prevent local recurrence of the tumor, but five months after the primary resection, the patient started complaining of a palpable mass in the right inguinal area, and radiologic examination detected a local tumor recurrence involving the sacrum. Additionally, serum levels of CEA and CA 19 - 9 had increased to 37.06 ng/mL and 5260 U/mL, respectively. Excisional biopsy of inguinal lymph node revealed metastatic adenocarcinoma. Subsequently, the patient received 5-Fluorouracil based systemic chemotherapy.

The Retrorectal space is a potential space defined anteriorly by the rectum, posteriorly by the sacrum, superiorly by the peritoneal reflection, inferiorly by the levator ani and coccygeus muscle and laterally by the ureters and iliac vessels.1,13 There are a variety of congenital, inflammatory and malignant disorders that may occur within this space. During the 8 mm to 35 mm gestational stage (35 days gestational age to 56 days gestational age) of human development, the embryo possesses a true tail and the primitive hindgut extends into this tail, which is caudal to the site of subsequent formation of the anus. This caudal extension is called the tailgut or postanal gut, and this tailgut usually completely regresses by 56 days of gestational age. The persistence of this embryological remnant is very rare and results in the development of TGC.1,6 Although TGC may clinically present in all age groups from neonates to adults, the anomaly is more commonly found in middle-aged females.1,2 The clinical presentation is frequently nonspecific and related to a mass effect pressing on the surrounding tissues; discomfort while sitting and rectal bleeding are common symptoms. If the mass becomes infected, it is often misdiagnosed as a pilonidal cyst, an anorectal fistula or a recurrent retrorectal abscess.1-4 As Hjermstad and Helwig1 pointed out in their review of 53 retrorectal cysts diagnosed over a 35-year period, the clinical diagnosis of a TGC is often delayed due to the general unfamiliarity with this entity and also because of its symptomatological mimicry of other more common diseases afflicting the anus and anal canal, including perianal fistulas and abscesses. Although a variety of pathologic diagnoses such as epidermal cyst, dermoid cyst and even teratoma were rendered on the 53 cases in their study, the precise histologic diagnosis of a TGC was made in only two instances. The histological features of a TGC can aid the physician in the diagnosis as they are quite distinctive from the other retrorectal cysts.1-12 Microscopically, the lesions are usually multicystic and are lined by a variety of epithelial cells commonly found in the adult and fetal gastrointestinal tract, including columnar, stratified columnar, transitional and squamous epithelia. Smooth muscle tissue bundles are almost always present in the vicinity of the cysts. However, the muscle bundles are often disorganized and are focally present; this is unlike the well-formed continuous 2-layer muscle coat seen in duplication cysts. The differential diagnosis includes teratomas, dermoid cysts, epidermal cysts and duplication cysts. Teratomas are composed of all three germ layers. Dermoid and epidermal cysts are usually unilocular and lined only by squamous epithelium; the dermoid cysts have dermal appendages and the epidermal cysts do not. Rectal duplication cysts, as mentioned before, have well-developed smooth muscle layers with myenteric plexus. In Korea, only 6 cases of TGC,11-16 including one case of carcinoid tumor11 and one case of adenocarcinoma12 have been reported. The female predominance and the average age of 40 years are almost identical to those patient parameters stated in several other reports.1-10 All of the patients had symptoms and half of them presented with perianal pain. Wide excision of the lesion were carried out in all cases and upon gross examination, all of the lesions appeared to be multicystic presacral masses with an average diameter of 10 cm. The radiographic findings of a TGC have been described.1,6,17 Barium enema examination shows an extrinsic retrorectal mass.1 Sonography examination shows a complex cystic mass in the retrorectal region. It can be distinguished from simple cyst by a strong internal echo due to multicystic nature of the mass and the presence of gelatinous material or inflammatory debris inside the cyst.17 CT scan shows a well-defined homogeneous retrorectal mass with the CT values ranging from water to soft-tissue density. The keratinous or inflammatory debris within a cyst may account for a more solid appearance. Because calcification is not a feature of TGC, its presence favors the diagnosis of a teratoma or malignancy. If malignant degeneration is present, the CT scan may show a loss of discrete margins, calcification inside the lesion and involvement of contiguous structures.17 MRI imaging reveals a hypointense lesion on T1-weighted images and a homogenously hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images. Although the malignant portions of the tumor are characterized by irregular wall thickening and intermediate signal intensity on both the T1- and T2-weighted images, MRI is probably not the best imaging modality to fully differentiate malignant lesions from benign lesions.6 Most of TGCs are benign, and malignant transformation of the epithelial component of a TGC has rarely been reported.2-12 On our computerized MEDLINE search from 1966 to 2004, only 10 cases of malignancy arising from TGC have been reported: five were adenocarcinoma,2-6 three carcinoid,7,8,11 one neuroendocrine carcinoma9 and one squamous cell carcinoma.10 The data for the nine previously reported cases are summarized in the Table 1. In Korea, one case of carcinoid tumor11 and one case of adenocarcinoma12 derived from TGCs has been reported, and there has been only one case of a serum CEA-producing adenocarcinoma within a TGC reported worldwide. To the best of our knowledge, our case is the first one that clearly showed an increase in serum CEA as well as serum CA19-9. An elevated level of serum CEA per se is not specific enough to permit a diagnosis of TGC adenocarcinoma to be made, but once a TGC malignancy has been diagnosed and it is shown to be associated with elevated level of CEA, it seems logical that CEA measurements can be used as a simple measure to assess the tumor's response to treatment. In our patient, normalization of CEA after radical resection was related to the total excision of tumor mass, and the rebound of the CEA serum level could be considered as an index to judge tumor recurrence. There were two incidences of recurrence in our patient. The first tumor recurrence could be attributed to an incomplete surgical resection in the year of 2001. Because there is always a high probability of tumor spillage in the process of needle biopsy, our patient underwent postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy. The high preoperative CEA serum level in our patient may serve to indicate the tumor's aggressive behavior, a poor prognosis and an early recurrence, as is the case in colorectal neoplasms.18 In addition, the poorly differentiated histology and tumor adhesion to adjacent organs probably contributed to the second recurrence of the tumor. The treatment guidelines for a recurred TGC tumor have not been documented due to the rarity of this disease. However, TGC embryologically originates from hindgut1 and there was an immunohistochemical study stating that the development of TGC adenocarcinoma follows the similar dysplasia-carcinoma sequence as observed for colorectal adenocarcinoma.3 Therefore, we decided to manage our patient along the lines of a rectal carcinoma and we started treatment with 5-Fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. The prognosis for malignant presacral lesions depends on the surgical performance of complete resection and the tumor histology, and there is a much better prognosis for endocrine tumors when compared with adenocarcinomas.7-9,19 The poor prognosis of adenocarcinoma arising from TGC due to local recurrence and metastasis after surgery has been reported in many cases.3-5 Yet in contrast, the patient reported on by Maruyama et al.2 was given adjuvant chemotherapy and had a good outcome, suggesting that adjuvant therapy is effective. Because a preoperative biopsy may fail to confirm the diagnosis of malignancy and the procedure may carry significant hazards such as spillage of malignant cells into the peritoneal cavity, the transrectal or presacral needle biopsy is only indicated for patients who are considered at high risk for surgery.1,4 Especially in the setting of a presacral heterogenous mass with CEA serum elevation, a biopsy should not be performed. The treatment of choice is complete excision of the lesion, with resection of the coccyx and an adequate surrounding margin of grossly normal tissue.1-6 Simple cyst excision or drainage will lead to recurrence or infection. Because of the multilocular nature of TGCs, a posterior surgical approach is recommended for the operative treatment of retrorectal masses or cysts that are located below the level of S4.1 Lesions that occur at a higher level are better addressed through an anterior laparotomy.20 If a malignant process is proven or even suspected, the combined abdominal/sacral approach, as we performed in our patient, is then recommended.4,21 In summary, our case would suggest that the TGC should be completely resected at the time of diagnosis, and also that serum CEA measurements can be used to assess the treatment response.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Barium enema study showing left-anterior displacement of the posterior wall of the rectum (arrows).

Fig. 2

(A) Saggital T1-weighted MRI scan showing presacral lesion with intermediate signal intensity invading surrounding structures (arrow). (B & C) Axial T1- and T2-weighted MRI scan showing multicystic mass with intermediate signal intensity (thick arrow). The cyst shows hypointense and hyperintense signal, respectively (thin arrow).

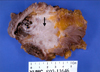

Fig. 3

On sectioning, the mass displays a firm gray-white appearance (thick arrow) and contains several, discrete cysts (thin arrow) filled with yellow gelatinous material. The ill-defined mass impinges on the outer wall of rectum, presacral soft tissue and coccygeal bone.

Fig. 4

(A) The tumor consisits of many scattered malignant glandular components with infiltrative growth to surrounding tissue (× 100 H&E stain). (B & C) The wall of cysts are lined by benign-looking ciliated columnar (B), columnar (C) and focal cuboidal epithelium (not shown), which is consistent with TGC (× 200 H&E stain).

References

1. Hjermstad BM, Helwig EB. Tailgut cysts, report of 53 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998. 89:139–147.

2. Maruyama A, Murabayashi K, Hayashi M, Nakano H, Isaji S, Uehara S, et al. Adenocarcinoma arising in a tailgut cyst: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998. 28:1319–1322.

3. Moreira AL, Scholes JV, Boppana S, Melamed J. p53 Mutation in adenocarcinoma arising in retrorectal cyst hamartoma (tailgut cyst): report of 2 cases-an immuohistochemistry/immunoperoxidase study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001. 125:1361–1364.

4. Schwarz RE, Lyda M, Lew M, Paz IB. A carcinoembryonic antigen-secreting adenocarcinoma arising within a retrorectal tailgut cyst: clinicopathologic considerations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000. 95:1344–1347.

5. Graadt van Roggen JF, Welvaart K, de Roos A, Offerhaus GJ, Hogendoorn PC. Adenocarcinoma arising within a tailgut cyst: clinicopathological description and follow up of an unusual case. J Clin Pathol. 1999. 52:310–312.

6. Lim KE, Hsu WC, Wang CR. Tailgut cyst with malignancy: MR imaging findings. Am J Roentgenol. 1998. 170:1488–1490.

7. Horenstein MG, Erlandson RA, Gonzalez-Cueto DM, Rosai J. Presacral carcinoid tumors: report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998. 22:251–255.

8. Edelstein PS, Wong WD, La Valleur J, Rothenberger DA. Carcinoid tumor: an extremely unusual presacral lesion. Report a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996. 39:928–942.

9. Mourra N, Caplin S, Parc R, Flejou JF. Presacral neuroendocrine carcinoma developed in a tailgut cyst: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003. 46:411–413.

10. Umar T, Mikel JJ, Poller DN. Carcinoma arising in a tailgut cyst diagnosed on fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology. Cytopathology. 2000. 11:129–132.

11. Song DE, Park JK, Hur B, Ro JY. Carcinoid tumor arising in a tailgut cyst of the anorectal junction with distant metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004. 05. 128:578–580.

12. Chung KJ, Lee YL. Adenocarcinoma arising from the tailgut cyst (in Korean). Korean Radiol Society. 1995. 33:399–402.

13. Kang JW, Kim SH, Kim KW, Moon SK, Kim CJ, Chi JG. Unusual perirenal location of a tailgut cyst. Korean J Radiol. 2002. 3:267–270.

14. Ahn BY, Jeong CS, Lee DH, Yu CS, Lee HJ, Lee MK, et al. Tailgut cyst- A case report (in Korean). J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 1998. 14:617–620.

15. Lee H, Oh JH, Cho SY, Yang DM, Ha SY. Two cases of Tailgut cyst (in Korean). J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2001. 17:209–212.

16. Lim MJ, Lee SN, Kim SS, Koo H, Kim OK. Tailgut cyst with Glomus Coccygeum (in Korean). Korean J Pathol. 1996. 30:643–645.

17. Johnson AR, Ros PR, Hjermstad BM. Tailgut cyst: Diagnosis with CT and Sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 1986. 147:1309–1311.

18. Marchena J, Acosta MA, Garcia-Anguiano F, Simpson H, Cruz F. Use of the preoperative levels of CEA in patients with colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003. 50:1017–1020.

19. Jao SW, Beart RW Jr, Spencer RJ, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM. Retrorectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985. 28:644–652.

20. Bohm B, Milsom JW, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Church JM, Oakley JR. Our approach to the management of congenital presacral tumors in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1993. 8:134–138.

21. Wang JY, Hsu CH, Changchien CR, Chen JS, Hsu KC, You YT, et al. Presacral tumor: A review of forty-five cases. Am Surg. 1995. 61:310–315.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download