Abstract

Here we report a case of 41-year-old man with a soft tissue density mass at right upper lung and palpable abscesses at right upper backside and right wrist. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography demonstrated a 7.8 × 5.0 cm mass with soft-tissue density in the upper lobe of the right lung with high metabolic activity. The infiltrative mass extended to adjacent chest wall soft tissue. Final diagnosis of pulmonary actinomycosis with multiple abscesses was made. The patient responded well to antibiotics treatment.

Actinomycosis, a rare chronic granulomatous infection induced by Actinomyces species, colonizes the mouth, colon, and vagina (1). Mucosal disruption may lead to infection at virtually any anatomic site of immunocompromised body, such as head and neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis region. In literature reports, about 50% of all cases appear in the head and neck region, with relatively rare appearance at other sites (2). 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is a highly sensitive but not specific radiotracer that can accumulate at various inflammation and infection sites. Only a few cases of actinomycosis appearance on 18F-FDG positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) have been documented recenlty (23456).

Here, we describe a rare appearance of pulmonary actinomycosis with intrapulmonary disseminated distribution and abscess formation on 18F-FDG PET/CT. We found that the involved bones demonstrated increased focal uptake of radiotracer on 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scintigraphy, which has not been reported to the best of our knowledge.

This report was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our institution. A 41-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with complaints of cough for 8 months. In addition, he had right thoracodorsal and shoulder discomfort as well as wrist swelling pain for 4 months. Physical examination found a palpable abscess at both right upper backside and right wrist. Blood routine examination and serum tumor marker analysis revealed no abnormality. A chest CT scan revealed a 7.8 × 5.0 cm lung mass in the right upper lobe with spiculated margins and irregular chest wall infiltration, suggesting peripheral lung carcinoma. Subsequently, a 99mTc-MDP whole bone scintigraphy was performed to determine whether there were bone metastasis. Bone scan (Fig. 1A, posterior) showed that the uptake of radiotracer was increased at the right third and fourth posterior ribs (small black arrows) as well as right multiple carpal bones (large black arrow). Regional chest and right wrist (Fig. 1B: B1, single photon emission computerized tomography [SPECT]; B2, CT; B3, SPECT/CT fusion) tomography imaging examinations found no osseous abnormality.

The patient underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT for further evaluation since this imaging method had improved sensitivity compared to 99mTc-MDP bone scintigraphy. 18F-FDG PET/CT (Fig. 1C, maximum intensity projection; Fig. 1D: D1, PET; D2, CT; D3, PET/CT fusion; Fig. 1G, axial; Fig. 1H, coronal; Fig. 1I, sagittal) demonstrated a 7.8 × 5.0 cm mass in the upper lobe of the right lung with soft-tissue density and spiculated margins similar to results of the previous CT scan. The density of the lesion was slightly asymmetrical with shaggy border. The mass had intense 18F-FDG accumulation with maximal standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 13.3. The infiltrative mass extended to adjacent chest wall, thoracodorsal muscle, and subcutaneous dermal tissues. The soft tissues at the right upper backside was swelling with a high activity (SUVmax = 9.2). Additionally, some opaque mottled shadows were distributed in multiple lobes of the right lung and the inferior lobe of the left lung (Fig. 1E1, F1, PET; Fig. 1E2, F2, CT; Fig. 1E3, F3, PET/CT fusion). The sizes of these nodules ranged from 0.3 cm to 1.1 cm in diameter. The SUVmax of the highest activity nodule was 5.7.

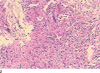

A CT-guided lung puncture biopsy was implemented to confirm the nature of the pulmonary mass. Pathological analysis revealed chronic inflammation with proliferation of fibrotic granulation tissue (Fig. 1J). Actinomyces odontolyticus was cultured from biopsy specimen. Several days later, 4-5 mL yellowish pus was leaked out of the previous puncture pore. A little pus was collected by squeezing the puncture pinhole after sterilization. In the meantime, 0.5 mL pus was aspirated by puncturing the right wrist abscess. Actinomyces odontolyticus was also cultured from different pus. Thus, a final diagnosis of pulmonary actinomycosis with multiple abscesses was made. Results of in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility tests for different pus were identical. The organism was sensitive to cefuroxime, levofloxacin, and penicillin. Finally, the patient received treatment with intravenous antibiotics (piperacillin-sulbactam combined with levofloxacin) followed by oral antibiotics (cefuroxime combined with levofloxacin) for 14 days. He recovered without complications.

Actinomycosis is a rare, chronic, and slowly progressive bacterial infection caused by several members of Actinomyces. Among six pathogenic species of Actinomyces spp., Actinomyces israelii is the most common human pathogen. In our case, a less common species (Actinomyces odontolyticus) was found.

Actinomycosis induces suppurative and granulomatous inflammation characterized by swelling with suppuration, sinus tract formation, and purulent discharge containing yellowish sulfur granules in severe cases. Although it is usually involved in oral and cervicofacial infections, other sites of immunocompromised body can be infected. Pulmonary actinomycosis represents approximately 15% of the total disease burden. It is mainly caused by aspiration of oropharyngeal or gastrointestinal secretions into the respiratory tract (7). The most common clinical symptoms of pulmonary actinomycosis are chest pain, productive cough, and dyspnea. These non-specific clinical presentations make pulmonary actinomycosis difficult to be diagnosed, often leading to misdiagnosis of malignancy rather than an infective disease (7).

Only a few authors have recently reported pulmonary actinomycosis appearance on 18F-FDG PET/CT (4891011). The general PET/CT finding of actinomycosis is intense hypermetabolism as in malignancy. The reported activity of pulmonary actinomycosis from literature is up to 33.1 (8). Because there is not much difference in PET/CT findings between actinomycosis and malignancy, utilization of PET/CT to rule out malignancy seems unnecessary. Therefore, pulmonary actinomycosis should be kept in mind for differential diagnosis of cases with intensive activity on 18F-FDG PET/CT.

Microbiological and pathological examinations with demonstration of Actinomyces are indispensable for correct diagnosis of actinomycosis. In our case, CT-guided lung puncture biopsy was implemented and abscesses were punctured to culture the actual bacteria. To avoid contaminations with other external bacteria, the specimen should be collected prior to antimicrobial therapy and carefully transported to the laboratory in anaerobic media. In addition, histopathologic finding of yellowish sulfur granules within pus is often necessary for differential diagnosis of actinomycosis (12).

Regarding treatment options, pulmonary actinomycosis has been known to respond well to penicillin. Intravenous administration of penicillin should be given followed by oral penicillin or amoxicillin (13). In cases of penicillin allergy or resistance, ceftriaxone, doxycycline, clindamycin, or fluoroquinolone is recommended. Response to therapy can be slow. It may take months. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be used as an adjunct to conventional therapy when the disease process is refractory to antibiotics. Surgical treatment may also be used as an alternative regimen for local pulmonary actinomycosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

41-year-old man with pulmonary actinomycosis imitating lung cancer on 99mTc-MDP bone scintigraphy.

A. Posterior. B. Uptake of radiotracer is increased at right third and fourth posterior ribs (small black arrows, A) and right multiple carpal bones (large black arrow, A).

Fig. 1

41-year-old man with pulmonary actinomycosis imitating lung cancer with whole body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan.

C. Maximum intensity projection showing mass at upper lobe of right lung and peripheral daughter lesions. D. 7.8 × 5.0 cm soft-tissue density mass is demonstrated. Mass has intense 18F-FDG accumulation (SUVmax = 13.3). E, F. Some opaque mottled shadows with 18F-FDG uptake are distributed in multiple lobes of right lung and inferior lobe of left lung. G-I. Infiltrative mass extended to adjacent chest wall, thoracodorsal muscle, and subcutaneous dermal tissues. SUVmax = maximal standardized uptake value, 18F-FDG PET/CT = 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography

References

1. Arora AK, Nord J, Olofinlade O, Javors B. Esophageal actinomycosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dysphagia. 2003; 18:27–31.

2. Mok GS, Choi FP, Chu WC. Actinomycosis imitating parotid cancer with metastatic lymph nodes in FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2011; 36:309–310.

3. Ho L, Seto J, Jadvar H. Actinomycosis mimicking anastomotic recurrent esophageal cancer on PET-CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2006; 31:646–647.

4. Singla S, Singh H, Mukherjee A, Karunanithi S, Bal C, Kumar R. Cervical and thoracic actinomycosis on (18)F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2014; 39:623–624.

5. Lim KT, Moon SJ, Kwon JS, Son YW, Choi HY, Choi YY, et al. Urachal actinomycosis mimicking a urachal tumor. Korean J Urol. 2010; 51:438–440.

6. Hsu CH, Lee CM, Chia CF, Lin YH. F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in an anorectal fistula with actinomycosis. Clin Nucl Med. 2004; 29:452–453.

7. Russo TA. Agents of actinomycosis. In : Mandell GL, editor. Principles and practice of infectious disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone;1995. p. 2645–2654.

8. Hoekstra CJ, Hoekstra OS, Teengs JP, Postmus PE, Smit EF. Thoracic actinomycosis imaging with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Clin Nucl Med. 1999; 24:529–530.

9. Kanda H, Nakamura Y, Nagata T, Fukumori K, Imoto Y, Tabata K, et al. [Surgery for pulmonary actinomycosis that was difficult to differentiate from lung cancer; report of a case]. Kyobu Geka. 2011; 64:864–867.

10. Kogure S, Yamamoto N, Watanabe F, Yuasa U, Tokui T, Shomura S. [Pulmonary actinomycosis which was clinically suggested lung cancer; report of a case]. Kyobu Geka. 2011; 64:254–257.

11. Okuda R, Izumo T, Yoshikawa M, Kakuta Y, Tamaoki J, Nagai A. [A case of thoracic actinomycosis in the left lung coexisting with pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma in the right lung]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2011; 49:103–107.

12. Taştepe AI, Ulaşan NG, Liman ST, Demircan S, Uzar A. Thoracic actinomycosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998; 14:578–583.

13. Yeung VH, Wong QH, Chao NS, Leung MW, Kwok WK. Thoracic actinomycosis in an adolescent mimicking chest wall tumor or pulmonary tuberculosis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008; 24:751–754.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download