Abstract

Although pulmonary artery aneurysms are a rare vascular anomaly, they are seen in a wide variety of conditions, such as congenital heart disease, infection, trauma, pulmonary hypertension, cystic medial necrosis and generalized vasculitis. To our knowledge, mycotic aneurysms caused by pulmonary actinomycosis have not been reported in the radiologic literature. Herein, a case of pulmonary actinomycosis complicated by mycotic aneurysm is presented. On CT scans, this case showed focal aneurysmal dilatation of a peripheral pulmonary artery within necrotizing pneumonia of the right lower lobe, which was successfully treated with transcatheter embolization using wire coils.

Infectious or mycotic aneurysms involving intrapulmonary arteries are a rare vascular abnormality, which can occur in association with a variety of microorganisms, such as bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Treponema pallidum, but rarely with fungi (1-4). Radiologic manifestations of thoracic actinomycosis are diverse, which include peripheral air-space consolidation, mass like opacity, cavitation, hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy, empyema, osteomyelitis and a soft tissue mass secondary to chest wall involvement, with eventual fistula formation (5). However, to our knowledge, mycotic aneurysms associated with actinomycosis have not been reported in the radiologic literature. Herein, a case of pulmonary mycotic aneurysm associated with thoracic actinomycosis with imaging findings is presented, which was successfully treated with transcatheter embolization using wire coils.

A 71-year-old man presented at our hospital with a 4-week history of a cough, blood-tinged sputum and general weakness. His medical history was marked by diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency and myocardial infarction. On admission, he had a body temperature of 37.8℃. Physical examination was remarkable only for inspiratory crackle over the right mid-lung, posteriorly. The routine laboratory data revealed an elevated WBC count of 14,120 cells/mm3, and a room air blood gas analysis gave the following results: PaO2=64 mmHg, PaCO2=30 mmHg, pH=7.29.

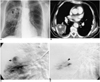

A chest radiograph obtained on admission showed oval-shaped opacity, with an air-fluid level in the right upper lung zone (Fig. 1A). He was treated with antibiotics for clinical impression of a lung abscess. The day after admission he developed a moderate amount of hemoptysis. A contrast-enhanced CT of the chest was performed to search for the source of bleeding, which showed a focal lesion of low attenuation, similar to that of water, involving both the posterior segment of the right upper lobe and the superior segment of the right lower lobe. In addition, a 1.5-cm hyperenhancing nodule, with the same attenuation as that of the aorta, was found within the lower portion of the lesion (Fig. 1B). The enhancing nodule was considered as an intrapulmonary aneurysm, which was thought to be related to the patient's hemoptysis.

The patient underwent pulmonary angiography for a definitive diagnosis and therapeutic intervention. A selective angiogram of the right pulmonary artery showed saccular dilatation of a peripheral pulmonary artery in the right lower lobe (Fig. 1C). The feeding artery was embolized with 3 mm diameter microcoils (Tornado, Cook, Bloom-ington, Ind) through a microcatheter, coaxially inserted from a 5-French catheter positioned in the segmental artery. Repeated angiography, performed on completion of the embolization, confirmed successful occlusion of the feeding artery, with no staining of the aneurysmal sac (Fig. 1D). He had no further hemoptysis. To evaluate the nature of the central lesion of low attenuation surrounding the intrapulmonary aneurysm, a CT-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed. A pathologic examination of the specimen revealed tiny sulfur granules in thick pus and gram-positive, filamentous, branching organisms within the stained granules, findings consistent with actinomycosis. The antibiotic treatment was adjusted to the use of ampicillin, which is effective against Actinomyces. During the following week of hospitalization, the patient's clinical condition was much improved. The patient was discharged on the 24 th hospital day.

Thoracic actinomycosis usually results from aspiration of infective materials in the oropharynx. The organism produces proteolytic enzymes that allow the infection to cross fascial planes. Therefore, if appropriate therapy is not instituted, pulmonary actinomycosis commonly spreads from an early pneumonic focus across lung fissures to involve the pleura and chest wall, with eventual fistula formation and drainage containing sulfur granules. Although the aggressive nature of the infiltration and frequent presentation of hemoptysis have been well described (5, 6), actinomycosis involving the pulmonary vasculature has rarely been documented. Only one case of mycotic pulmonary aneurysm due to actinomycosis has been reported in the medical literature (1); however, to our knowledge, imaging findings, including the CT appearance of a mycotic aneurysm associated with actinomycosis, have not been reported.

Aneurysms of any type affecting the pulmonary arteries are very rare compared with aortic, intracranial or other major vascular locations. They may occur in association with congenital cardiovascular anomalies, infection, trauma, generalized vasculitis or pulmonary hypertension (7). Of these conditions, infection is the major cause of pulmonary aneurysms. Mycotic or infectious pulmonary aneurysms are most commonly caused by pyogenic microorganisms, including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus; however, treponemal, mycobacterial, but rarely fungal organisms, including Aspergillus and Candida species, have been reported (1-4). Tuberculosis and syphilis, once the major causes of mycotic pulmonary aneurysms, are now better controlled since the introduction of antibiotics (7).

The proposed pathologic mechanisms of mycotic pulmonary aneurysm include direct involvement of an adjacent pulmonary artery from a focus of suppurating pulmonary infection, as in tuberculosis, ischemic injury to the pulmonary arterial wall as a result of infection of the vasa vasorum, as in syphilis, and direct extension into a vessel wall from an intraluminal septic thromboembolus or the blood itself, as in bacterial endocarditis (2, 3). Among these mechanisms, the first was thought to be the most likely to be responsible for the development of the pulmonary aneurysm in our case. Both true and false aneurysms have been found in the mycotic aneurysm. Virulent organisms produce severe destruction of all layers of the arterial wall, resulting in the formation of a false aneurysm, whereas indolent organisms tend to cause a true aneurysm, as the arterial wall is less severely damaged (8).

The radiographic appearance of a mycotic pulmonary aneurysm includes well- or ill-defined pulmonary nodules or focal parenchymal consolidation, which are frequently nondiagnostic and indistinguishable from those of infectious or neoplastic conditions (9). Rapid change in the contour of a nodule may occasionally suggest a mycotic aneurysm, but as in our patient, a mycotic aneurysm associated with necrotizing pneumonia can be difficult to diagnose. Although pulmonary angiography was previously the gold standard of diagnosis, CT and MRI have recently become important alternatives. Both contrast-enhanced CT and MR imaging clearly show the vascular nature of a mass like lesion resulting from a pulmonary aneurysm. In our patient, CT disclosed a hyperenhancing nodule, connected with a pulmonary vessel within the parenchymal lesion of low attenuation. The density of the enhancing nodule had the same attenuation as the enhancing vessels, which was virtually diagnostic of a pulmonary aneurysm.

Experience in the management of mycotic pulmonary aneurysms is limited as their diagnosis is rare. Their management is usually surgical, and involves aneurysmectomy, lobectomy, aneurysmorrhaphy or banding (2). In addition, as in our patient, alternative nonsurgical therapeutic procedures, including occlusion of aneurysm with steel coils or detachable balloons, have been reported (3, 4).

In summary, a case of a mycotic pulmonary aneurysm occurring in association with necrotizing pneumonia, caused by Actinomyces, where the patient was successfully treated with transcatheter intervention with steel coils is reported.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

A 71-year-old man with mycotic pulmonary aneurysm caused by actinomycosis.

A. Chest radiograph shows focal parenchymal opacity with air-fluid level (arrow) in right upper lung zone. Pleural thickening with calcification due to previous tuberculous pleurisy is seen in left lower hemithorax.

B. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows localized area of low attenuation (closed arrows) in superior segment of right lower lobe. Note hyperenhancing nodule (open arrow) with same attenuation as that of aorta.

C. Selective pulmonary angiogram of right lower lobe obtained before embolization shows peripheral pulmonary artery aneurysm (closed arrow). Feeding artery (open arrow) arises from superior segmental artery of right lower lobe.

D. Angiogram obtained after placement of coils (arrow) shows occlusion of aneurysm sac. Note no detectable staining of pulmonary aneurysm.

References

1. Navarro C, Dickinson T, Kondlapoodi P, Hagstrom J. Mycotic aneurysms of the pulmonary arteries in intravenous drug addicts: report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1984. 76:1124–1131.

2. Bartter T, Irwin RS, Nash G. Aneurysms of the pulmonary arteries. Chest. 1988. 94:1065–1075.

3. Renie WA, Rodeheffer RJ, Mitchell S, Balke WC, White RI. Balloon embolization of a mycotic pulmonary artery aneurysm. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982. 126:1107–1110.

4. Remy J, Smith M, Lemaitre L, Marache P, Fournier E. Treatment of massive hemoptysis by occlusion of a Rasmussen aneurysm. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980. 135:605–606.

5. Cheon JE, Im JG, Kim MY, Lee JS, Choi GM, Yeon KM. Thoracic actinomycosis: CT findings. Radiology. 1998. 209:229–233.

6. Bennhoff DF. Actinomycosis: diagnosis and therapeutic considerations and a review of 32 cases. Laryngoscope. 1984. 94:1198–1217.

7. Chung CW, Doherty JU, Kotler R, Finkelstein A, Dresdale A. Pulmonary artery aneurysm presenting as a lung mass. Chest. 1995. 108:1164–1166.

8. Burke DR. Baum S, editor. Aneurysms of the abdominal aorta. Abrams' angiography. 1997. 4th ed. Boston: Little Brown & Company;1073–1100.

9. Jaffe RB, Condon VR. Mycotic aneurysm of the pulmonary artery and aorta. Radiology. 1975. 116:291–298.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download