1. World Health Organization. Alcohol: Fact Sheet. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2015.

3. Chung W, Lim S, Lee S. Why is high-risk drinking more prevalent among men than women? Evidence from South Korea. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12:101.

4. Delker E, Brown Q, Hasin DS. Alcohol consumption in demographic subpopulations: an epidemiologic overview. Alcohol Res. 2016; 38(1):7–15.

5. Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004; 24(8):981–1010.

6. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt L. Possible contributors to the gender differences in alcohol use and problems. J Gen Psychol. 2006; 133(4):357–374.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (US). Alcohol: a Women's Health Issue. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department and Human Services;2003.

9. Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GL, Graham K, Irving H, Kehoe T, et al. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2010; 105(5):817–843.

10. Sauerbrun-Cutler MT, Segars JH. Do in utero events contribute to current health disparities in reproductive medicine? Semin Reprod Med. 2013; 31(5):325–332.

11. Martin SL, Beaumont JL, Kupper LL. Substance use before and during pregnancy: links to intimate partner violence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003; 29(3):599–617.

12. Lim WY, Fong CW, Chan JM, Heng D, Bhalla V, Chew SK. Trends in alcohol consumption in Singapore 1992–2004. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007; 42(4):354–361.

13. Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008; 93(1-2):21–29.

14. Bratberg GH, Wilsnack SC, Wilsnack R, Håvås Haugland S, Krokstad S, Sund ER, et al. Gender differences and gender convergence in alcohol use over the past three decades (1984–2008), the HUNT Study, Norway. BMC Public Health. 2016; 16:723.

15. Bloomfield K, Grittner U, Kramer S, Gmel G. Social inequalities in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems in the study countries of the EU concerted action ‘Gender, Culture and Alcohol Problems: a Multi-national Study’. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 2006; 41(1):i26–i36.

16. Colell E, Sanchez-Niubo A, Ferrer M, Domingo-Salvany A. Gender differences in the use of alcohol and prescription drugs in relation to job insecurity. Testing a model of mediating factors. Int J Drug Policy. 2016; 37:21–30.

17. Thapa N, Aryal KK, Puri R, Shrestha S, Shrestha S, Thapa P, et al. Alcohol consumption practices among married women of reproductive age in Nepal: a population based household survey. PLoS One. 2016; 11(4):e0152535.

18. Romans-Clarkson SE, Walton VA, Herbison GP, Mullen PE. Alcohol-related problems in New Zealand women. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1992; 26(2):175–182.

19. Matheson FI, White HL, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Glazier RH. Drinking in context: the influence of gender and neighbourhood deprivation on alcohol consumption. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012; 66(6):e4.

21. Lee HY, Kim J, Cin BC. Empirical analysis on the determinants of income inequality in Korea. Int J Adv Sci Tech. 2013; 53:95–110.

23. Monk-Turner E, Turner CG. Sex differentials in earnings in the South Korean labor market. Fem Econ. 2001; 7(1):63–78.

24. Kim W, Kim S. Women's alcohol use and alcoholism in Korea. Subst Use Misuse. 2008; 43(8-9):1078–1087.

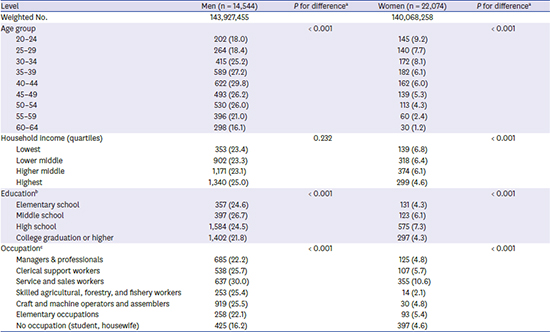

25. Hong JW, Noh JH, Kim DJ. The prevalence of and factors associated with high-risk alcohol consumption in Korean adults: the 2009–2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One. 2017; 12(4):e0175299.

26. Park HA. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey as a primary data source. Korean J Fam Med. 2013; 34(2):79.

27. Ryu SY, Crespi CM, Maxwell AE. Drinking patterns among Korean adults: results of the 2009 Korean community health survey. J Prev Med Public Health. 2013; 46(4):183–191.

30. Yang Y, Land KC. Age-period-cohort analysis of repeated cross-section surveys: fixed or random effects? Sociol Methods Res. 2008; 36(3):297–326.

31. Mulia N, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Witbrodt J, Bond J, Williams E, Zemore SE. Racial/ethnic differences in 30-year trajectories of heavy drinking in a nationally representative U.S. sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017; 170:133–141.

32. Abbey A, Smith MJ, Scott RO. The relationship between reasons for drinking alcohol and alcohol consumption: an interactional approach. Addict Behav. 1993; 18(6):659–670.

33. Martinez P, Røislien J, Naidoo N, Clausen T. Alcohol abstinence and drinking among African women: data from the World Health Surveys. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11:160.

34. Kuntsche S, Gmel G, Knibbe RA, Kuendig H, Bloomfield K, Kramer S, et al. Gender and cultural differences in the association between family roles, social stratification, and alcohol use: a European cross-cultural analysis. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 2006; 41(1):i37–i46.

35. Iwamoto DK, Kaya A, Grivel M, Clinton L. Under-researched demographics: heavy episodic drinking and alcohol-related problems among Asian Americans. Alcohol Res. 2016; 38(1):17–25.

36. Diala CC, Muntaner C, Walrath C. Gender, occupational, and socioeconomic correlates of alcohol and drug abuse among U.S. rural, metropolitan, and urban residents. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004; 30(2):409–428.

37. Olkinuora M. Alcoholism and occupation. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1984; 10(6 Spec No):511–515.

38. Savikko A, Lanne M, Spak F, Hensing G. No higher risk of problem drinking or mental illness for women in male-dominated occupations. Subst Use Misuse. 2008; 43(8-9):1151–1169.

39. Barnes AJ, Brown ER. Occupation as an independent risk factor for binge drinking. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013; 39(2):108–114.

40. Walker S, Higgs S, Terry P. Estimates of the absolute and relative strengths of diverse alcoholic drinks by young people. Subst Use Misuse. 2016; 51(13):1781–1789.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download