2. Burns R, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Graney MJ. Interdisciplinary geriatric primary care evaluation and management: two-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000; 48(1):8–13.

3. Rubenstein L. The clinical effectiveness of multidimensional geriatric assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983; 31(12):758–762.

4. Shah PN, Maly RC, Frank JC, Hirsch SH, Reuben DB. Managing geriatric syndromes: what geriatric assessment teams recommend, what primary care physicians implement, what patients adhere to. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997; 45(4):413–419.

5. Choi H. Present and future of Korean geriatrics. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2011; 15(2):71–79.

6. Lee E. Prospect and present of geriatric field in clinical medicine. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2008; 12(3):125–128.

7. Kim KI, Lee JH, Kim CH. Impaired health-related quality of life in elderly women is associated with multimorbidity: results from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Gend Med. 2012; 9(5):309–318.

8. Yoo HJ. Clinical implications of geriatric syndromes. J Korean Med Assoc. 2014; 57(9):738–742.

9. Kim S, Kim K. Management of multimorbidity in the ederly. J Korean Med Assoc. 2014; 57(9):743–748.

11. Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty defined by deficit accumulation and geriatric medicine defined by frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011; 27(1):17–26.

12. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007; 55(5):780–791.

13. Won CW, Yoo HJ, Yu SH, Kim CO, Dumlao LC, Dewiasty E, et al. Lists of geriatric syndromes in the asian-pacific geriatric societies. Eur Geriatr Med. 2013; 4(5):335–338.

14. Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, Syin D, Bandeen-Roche K, Patel P, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010; 210(6):901–908.

15. Partridge JS, Harari D, Martin FC, Dhesi JK. The impact of pre-operative comprehensive geriatric assessment on postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing scheduled surgery: a systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2014; 69:Suppl 1. 8–16.

16. Ga H. Ten years of long-term care insurance in Korea: light and shade from a geriatric point of view. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2017; 21(4):147–148.

18. Do S, Shin E. Increase of medical service use in older adults and implications. Health Welf Issue Focus. 2012; (167):

19. Ga H. New system for Korean nursing home contracted physicians began in 2017. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2017; 21(1):35–36.

20. Kim S, Won CW, Ga H. Nursing homes and their contracted doctors: Korean experience. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015; 16(6):533–534.

22. Park IS, Kim SK. Korean elderly long-term care insurance system and long-term care hospital. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2008; 12(2):68–73.

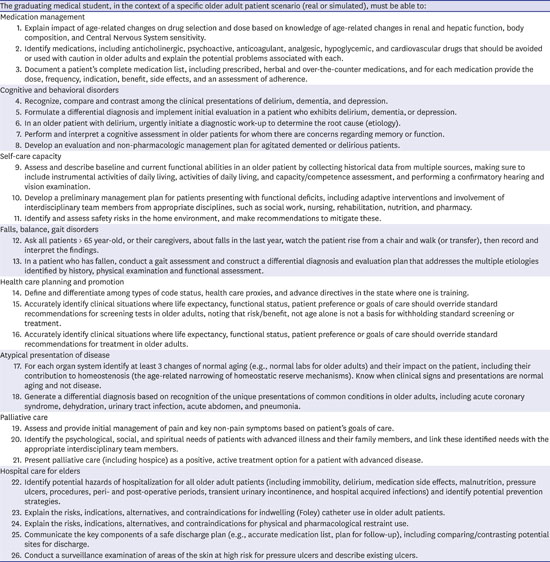

23. Leipzig RM, Granville L, Simpson D, Anderson MB, Sauvigné K, Soriano RP. Keeping granny safe on July 1: a consensus on minimum geriatrics competencies for graduating medical students. Acad Med. 2009; 84(5):604–610.

28. Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010–2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012; 10(6):503–509.

30. American board of medical specialties (ABMS). Updated 2018. Accessed February 1, 2018.

http://www.abms.org/.

31. Callahan KE, Tumosa N, Leipzig RM. Big ‘G’ and little ‘g’ Geriatrics education for physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017; 65(10):2313–2317.

34. Burton JR. Clinical fellowship training in geriatric medicine. Am J Med. 1994; 97(4 4A):20S–22S.

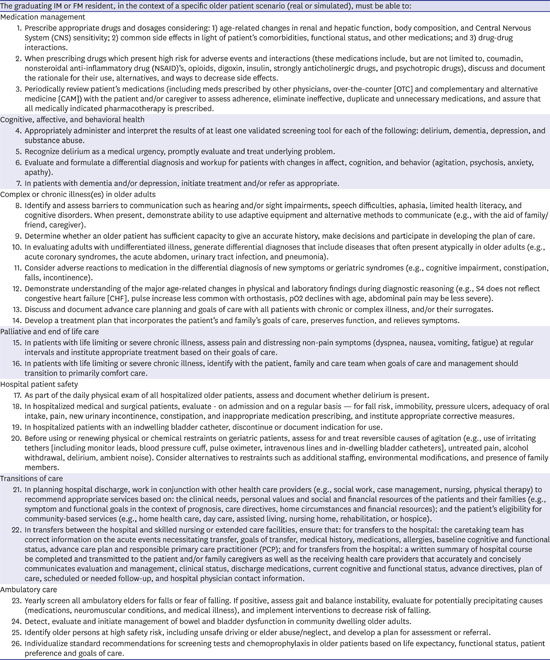

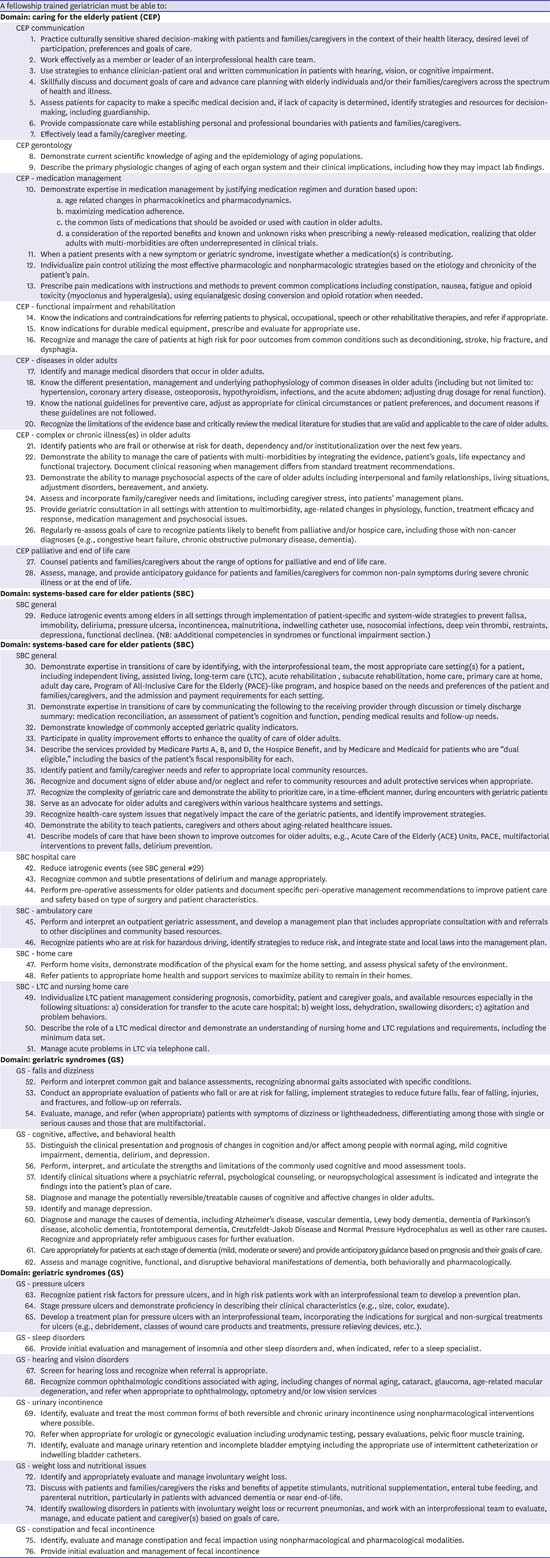

35. Parks SM, Harper GM, Fernandez H, Sauvigne K, Leipzig RM. American Geriatrics Society/Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs curricular milestones for graduating geriatric fellows. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014; 62(5):930–935.

37. Rivera V, Yukawa M, Aronson L, Widera E. Teaching geriatric fellows how to teach: a needs assessment targeting geriatrics fellowship program directors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014; 62(12):2377–2382.

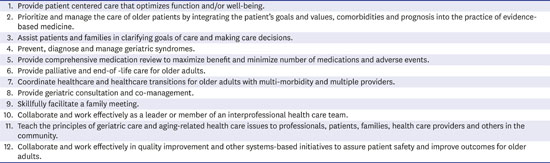

38. Leipzig RM, Sauvigné K, Granville LJ, Harper GM, Kirk LM, Levine SA, et al. What is a geriatrician? American Geriatrics Society and Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs end-of-training entrustable professional activities for geriatric medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014; 62(5):924–929.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download