Abstract

Recently reports on toxocariasis are increasing by serodiagnosis in Korea. A previously healthy 17-yr-old boy complained of headache, fever, dyspnea, and anorexia. He showed symptoms and signs of eosinophilic meningitis with involvement of the lungs and liver. Specific IgG antibody to Toxocara canis larval antigen was positive in serum and cerebrospinal fluid by ELISA. He took raw ostrich liver with his parents 4 weeks before the symptom onset. His parents were seropositive for T. canis antigen but had no symptoms or signs suggesting toxocariasis. This is the first report of toxocariasis in a family due to ingestion of raw ostrich liver in Korea.

Toxocara canis is a nematode of the Ascaridae family, which lives in the lumen of the small intestine of dogs (1, 2). It produces eggs, which are passed in feces and embryonate in the soil. T. canis is known to infect various unusual paratenic hosts such as cats, foxes, cows, monkeys, pigs, lambs, mice, rats, chickens and pigeons, by means of eggs or larvae being ingested with their prey or soil (1-3). Humans are infected by ingestion of contaminated embryonated eggs from soil, through direct contact with dogs or cats, eating raw vegetables, or ingestion of larvae from raw or undercooked giblets and muscles (4, 5). In infected humans, the eggs hatch in the intestine and the developing larvae cross the intestinal wall to enter the blood stream, and then migrate to the liver, lungs, eyes, and the central nervous system (CNS), myocardium or musculature (6, 7).

Recently reports on toxocariasis are increasing by serodiagnosis in Korea (8). A Korean survey reported a seropositive rate for toxocariasis was 5% in rural area (9). One of the major causes of high incidence of toxocariasis may result from eating raw animal liver (3, 4, 10). A study revealed 66.7% subjects were Toxocara seropositive among the patients with unexplained pulmonary patchy infiltrate on chest computed tomography (CT) scans. Eating raw cow liver is known to increase incidence of the seropositivity by 7.8 times among them (10). We describe a patient's clinical record with meningitis by Toxocara canis and his family with asymptomatic toxocariasis after ingestion of raw ostrich liver.

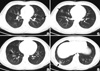

In February 2010, a previously healthy 17-yr-old boy was transferred to Seoul National University Hospital with frontal headache, fever, dyspnea, and anorexia, which developed 8 days before the transfer. Physical and neurologic examination recognized no remarkable findings, such as wheezing, hepatomegaly, and nuchal rigidity. Fundoscopic examination was normal. Initial laboratory results showed slightly elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 10,050 cells/µL with eosinophilia (2,440 cells/µL) and serum IgG elevated to 529.4 (normal range, 1.0-183 IU/mL). There was marked lymphocytic pleocytosis in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (1,420 cell/µL), in which 75% of WBCs were eosinophils. CSF protein, glucose, and IgG index were all within normal ranges. Gram stain, culture, and latex agglutinin tests for bacteria were negative, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis and viruses as well as cultures for fungi showed also negative results. Magnetic resonance (MR) scans of the brain showed no abnormal findings. Paranasal sinus radiography showed no specific findings. On CT of the chest revealed multifocal slight, patch ground glass opacities in both lung fields, which was consistent with eosinophilic pneumonia (Fig. 1). Abdominal CT showed a small (12 mm) hypodense nodule in the liver, which was most likely eosinophilic granuloma. The results of tests for Legionella spp., (L. longbeachae sg., L. micdadei), Leptospira, Brucella, Coxiella burnetii, tsutsugamushi, and ameba were all negative. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), anti-double stranded DNA antibody, antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor were also negative. Suspecting of eosinophilic meningitis with the lung and liver infiltration caused by helminth infection, specific IgG antibodies to various parasite antigens were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The specific IgG antibody to Toxocara canis larval antigen was positive by ELISA with absorbances of 0.375 and 0.439 (cut off value > 0.250) in both serum and CSF respectively. The results of ELISA for Echinococcus sp., Anisakis simplex, Fasciola hepatica, Tricinella spiralis, Schistosoma spp., Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Clonorchis sinensis, Paragnoimus sp., cysticercus cellulosae, and sparganum were all negative.

He had no allergy, autoimmune disease and malignancy. He denied regular consumption of medication. He had no history of travel abroad or recent contact to pets. He lived in a dormitory located in an urban area and occasionally visited his parents' in the urban area during weekends. His parents owned a stock farm away from their dwelling house and raised ostriches, cows and dogs. He ate raw ostrich liver with his parents about 4 weeks before the symptom onset. Although his parents had no specific symptoms or signs, the results of ELISA using their serum showed positive absorbance of 0.391 for his 54-yr-old father and 0.316 for 50-yr-old mother to T. canis antigen. His 21-yr-old brother, who did not eat the raw ostrich liver, showed no reactivity to T. canis antigen with absorbance of 0.098. Complete blood cell (CBC) tests on his mother and brother showed eosinophilia only in his mother (WBC 7,100, eosinophil 15.5%).

Albendazole was administered to the patient and his parents for 2 weeks. This led to significant symptomatic improvement. Follow-up CBC of the patient showed reduced eosinophil count (WBC 7,500, eosinophil 10.2%) 1 month later and showed normalization (WBC 7,400, eosinophil 2.3%) 1 yr later.

Toxocariasis is classified into 4 types (1). Type 1 is asymptomatic toxocariasis which remains inapparent and composes of majority. Type 2, covert or common toxocariasis, is usually manifested as mild and focal impairment such as weakness, pruritus, rash, and so on (11). Type 3, classical visceral larva migrans usually seen in children, presents with general illness with fever, skin rash, pharyngitis, cervical lymphadenitis, lethargy, respiratory symptoms such as wheeze, cough, and pneumonia due to lung involvement. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as anorexia, vomiting, and abdominal pain due to hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, myalgia, arthralgias, and hypereosinophilia or hypergammaglobulinemia are also common (12, 13). The last one, type 4, is neurological toxocariasis including ocular involvement. In experiments, T. canis larvae are neurotropic in infected primates (14) as well as rodents (15, 16). Reported CNS involvement of T. canis is presented as meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis, or some combinations. Cerebral vasculitis, optic neuritis, extramedullary tumors, seizure and isolated behavior disorder are rarer clinical manifestation of CNS infection (1, 17, 18).

The present boy complained headache, fever, dyspnea, and anorexia. Most of them were nonspecific but the symptom combination assumed a certain systemic infection. Since his CSF included numerous WBCs with dominant eosinophils, the symptoms must have been induced by eosinophilic meningitis. In addition to this, his chest CT visualized multifocal slight, patch ground glass opacities in both lung fields. The findings in the lungs were compatible with those of eosinophilic pneumonia. The abdominal CT recognized a focal dense nodule of 12 mm diameter in the liver. The liver nodule may be an image of the liver granuloma. The clinical manifestations and CT images of the patient strongly suggested that any helminthiasis had involved the meninges, lungs, and liver simultaneously. ELISA using multi-antigens could differentiate the causative agents among several tissue invading helminthiases. The serum and CSF of the patient were strongly positive for specific antibodies to the antigen of Toxocara canis larvae but negative for 10 other antigens of helminthes. Any other bacterial or viral infections were excluded by intensive laboratory works. The present case was diagnosed as the type 3 and 4 toxocariasis, showing meningitis, pneumonitis, and liver granuloma.

The present patient had a history of eating raw liver of ostriches 4 weeks before the onset. The period of 4-weeks might be an enough duration of worm invasion and inflammatory response in the host. During the period, he must have been involved of his liver and lungs before the CNS but missed it. He could note subjective symptoms due to meningitis and pneumonitis together. The source of his infection must be the raw liver of ostriches because eating the liver was the only related history. Toxocariasis by ingestion of raw liver of cows, chickens, pigs or lamb has been well-known (3-5) and the impacts of the habitual eating of raw cow liver on toxocariasis have been evaluated (3, 10). Ostrich (Struchio camelus domesticus) is an imported animal for commercial farming to produce feather and meat. Since the eggs of T. canis remain viable in soil for months or years, the infection of farmed ostriches was presumed to be from contaminating feces of nearby dogs.

The severity of host damage in toxocariasis depends on the host's age and immunocompetence, affected tissues, the amount of ingested larvae and whether previous exposure had occurred (13, 19). The reason, why the boy alone manifested overt symptoms although his parents were exposed to the pathogen together and seropositive, may be related with the number of migrating larvae or host's age.

We report a human case of neurotoxocariasis and visceral larva migrans caused by ingestion of raw ostrich liver. In addition, this is the first case of toxocariasis in family. Misbelief that raw liver of animals is beneficial to health can lead to familial infection. Eating raw liver of animals should be actively discouraged. Physicians should pay more attention to toxocariasis for patients with eosinophilia and organ involvement.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Computed tomography (CT) scan findings of the chest. Multiple nodules with ground glass opacity halo in the left upper lung field (A) and ill defined patches of nodular ground glass opacity are shown in the right middle (B) and the right lower lung field (C, D), which involve mainly the peripheral regions of the both lungs (arrows).

References

1. Finsterer J, Auer H. Neurotoxocariasis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007. 49:279–287.

2. Graeff-Teixeira C, da Silva AD, Yoshimura K. Update on eosinophilicc meningoencephalitis and its clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009. 22:322–348.

3. Choi D, Lim JH, Choi DC, Paik SW, Kim SH, Huh S. Toxocariasis and ingestion of raw cow liver in patients with eosinophilia. Korean J Parasitol. 2008. 46:139–143.

4. Nagakura K, Tachibana H, Kaneda Y, Keto Y. Toxocariasis possibly caused by ingesting raw chicken. J Infect Dis. 1989. 160:735–736.

5. Sturchler D, Weiss N, Gassner M. Transmission of toxocariasis. J Infect Dis. 1990. 162:571.

6. Overgaauw PA. Aspects of Toxocara epidemiology: human toxocariosis. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1997. 23:215–231.

7. Haralambidou S, Vlacheaki E, Ioannidou E, Milioni V, Haralambidis S, Klonizakis I. Pulmonary and myocardial manifestations due to Toxocara canis infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2005. 16:601–602.

8. Lim JH. Foodborne eosinophilia due to visceral larva migrans: a disease abandoned. J Korean Med Sci. 2012. 27:1–2.

9. Park HY, Lee SU, Huh S, Kong Y, Magnaval JF. A seroepidemiological survey for toxocariasis in apparently healthy residents in Gangwon-do, Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2002. 40:113–117.

10. Yoon YS, Lee CH, Kang YA, Kwon SY, Yoon HI, Lee JH, Lee CH. Impact of toxocariasis in patients with unexplained patchy pulmonary infiltrate in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2009. 24:40–45.

11. Taylor MR, Keane CT, O'Connor P, Girdwood RW, Smith H. Clinical features of covert toxocariasis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1987. 19:693–696.

12. Magnaval JF, Glickman LT, Dorchies P, Morassin B. Highlights of human toxocariasis. Korean J Parasitol. 2001. 39:1–11.

13. Xinou E, Lefkopoulos A, Gelagoti M, Drevelegas A, Diaakou A, Milonas I, Dimitriadis AS. CT and MR imaging findings in cerebral toxocaral disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003. 24:714–718.

14. Glickman L, Summers BA. Experimental Toxocara canis infection in Cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Am J Vet Res. 1983. 44:2347–2354.

15. Good B, Holland CV, Stafford P. The influence of inoculum size and time post-infection on the number and position of Toxocara canis larvae recovered from the brains of outbred CD1 mice. J Helminthol. 2001. 75:175–181.

16. Fan CK, Lin YH, Du WY, Su KE. Infectivity and pathogenicity of 14-month-cultured embryonated eggs of Toxocara canis in mice. Vet Parasitol. 2003. 113:145–155.

17. Vidal JE, Sztajnbok J, Seguro AC. Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis due to Toxocara canis: case report and review of the literature. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003. 69:341–343.

18. Eberhardt O, Bialek R, Nagele R, Dichgans J. Eosinophilic meningomyelitis in toxocariasis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005. 107:432–438.

19. Despommier D. Toxocariasis: clinical aspects, epidemiology, medical ecology, and molecular aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003. 16:265–272.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download