This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Airway management during carinal resection should provide adequate ventilation and oxygenation as well as a good surgical field, but without complications such as barotraumas or aspiration. One method of airway management is high frequency jet ventilation (HFJV) of one lung or both lungs. We describe a patient undergoing carinal resection, who was managed with HFJV of one lung, using a de-ballooned bronchial blocker of a Univent tube without cardiopulmonary compromise. HFJV of one lung using a bronchial blocker of a Univent tube is a simple and safe method which does not need additional catheters to perform HFJV and enables the position of the stiffer bronchial blocker more stable in airway when employed during carinal resection.

Keywords: Carinal Resection, High Frequency Jet Ventilation, One Lung Ventilation, Univent Tube

INTRODUCTION

Carinal resection is associated with high rates of morbidity, making the procedure challenging task for both thoracic surgeons and anesthesiologists (

1). It is essential to provide adequate ventilation and oxygenation during airway manipulation without disturbing the surgical field. This may be accomplished using high frequency jet ventilation (HFJV) with a suction catheter (

2). This case report describes the successful use of a bronchial blocker of a Univent tube (Fuji Systems Corporation, Japan) for HFJV of one lung in a patient undergoing carinal resection.

CASE REPORT

A 60-yr old man presented for resection of a carinal tumor. He had no other medical problems. He has suffered from cough and sputum for about 3 months before visiting our hospital. His body weight and height were 64.5 kg and 171.7 cm, respectively. His preoperative electrocardiogram, chest radiography, and laboratory findings were all within normal limits. The preoperative arterial blood gas analysis result under room air was normal. The chest computed tomogram revealed a protruding lesion in the posterior portion of the trachea, which was suspected to be malignant (

Fig. 1). Anesthesia was induced with etomidate 14 mg, rocuronium 50 mg, and glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg, and was uneventful. Tracheal intubation with a Univent tube was performed. With the aid of fiberoptic bronchoscopy, the bronchial blocker was positioned correctly at the right main bronchus. An arterial catheter was placed at the left radial artery. Total intravenous anesthesia with propofol (Diprivan®, Astrazeneca, London, UK) and remifentanil (Ultiva®, GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK) using a Target Controlled Infusion pump (Orchestra®, Fresenius Vial, Paris, France) under Bispectral Index (A2000xp Monitor®, ASPECT, Norwood, USA) monitoring was carried out with 100% O

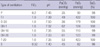

2. After the induction, the arterial blood gas analysis under two lung ventilation with a tidal volume of 10 mL/kg and a respiratory rate of 10 breaths/min was acceptable (

Table 1).

The operation was performed via a right thoracotomy.

During the exposure of the carina, the balloon of the bronchial blocker was inflated to collapse the right lung. The right main bronchus was incised under left one lung ventilation. After the right main bronchus was severed from the trachea, the balloon of the bronchial blocker was deflated and withdrawn up to the trachea. The tumor on the carina was removed by separating the left main bronchus from the trachea. The bronchial blocker of a Univent tube was immediately advanced without difficulty to the surgical field, and the surgeon introduced the proximal tip of the bronchial blocker into the left main bronchus without ballooning. The distal tip of the bronchial blocker was connected to a high frequency jet ventilator and HFJV was commenced (

Fig. 2). The jet ventilator delivered 100% O

2 with a respiratory rate of 2 Hz, a driving pressure of 15 psi (pound per square inch) and an inspiratory time of 25%. Under HFJV of the left lung, the left main bronchus was anastomosed end-to-end with the trachea, and the right main bronchus was anastomosed end-to-side with the lateral wall of the trachea. No adverse events were observed, and both vital signs and O

2 saturation (measured using pulse oximeter) were maintained without disturbance of the surgical field. After completing the anastomoses, we removed the bronchial blocker and ventilated both lungs with the Univent tube. The patient was kept in a position of head flexion from the time that construction of anastomoses commenced.

The HFJV and one lung ventilation using bronchial blocker were performed for about 30 min and 155 min, respectively. The operation took a total of 390 min, at the end of which the patient was extubated after it was confirmed that he was fully awake and showed adequate muscle strength. The patient showed no symptoms of respiratory distress after extubation. The patient was cared in the intensive care unit for 3 days without any complications. On the eighth day, good healing of anastomoses and good patency of distal bronchi were verified by bronchoscope. He was discharged on the postoperative tenth day.

DISCUSSION

There are several methods in airway management during carinal resection. First, the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is feasible but there is a risk of bleeding after terminating CPB (

3,

4). Second, the single lumen endotracheal tube can be used. It is advanced into the left main bronchus for one lung ventilation during separating the right main bronchus from the trachea and withdrawn to the trachea during separating the left main bronchus from the trachea (

3,

4). After separating the airway, one or two secondary sterile tubes from surgical field are inserted at dissected bronchial stump during anastomoses while single lumen endotracheal tube is remained at the trachea (

3,

5). Third, double lumen tube can be used. Bronchial lumen of double lumen tube is used during anastomoses instead of single lumen tube. The second and third one have some disadvantages that the tube may interfere the surgical field and repeated insertion and removal of tube may cause stump injury (

2). Fourth, the HFJV can be applied. HFJV has been shown to be appropriate in patients with disrupted major airways, including patients with tracheal and bronchial problems (

3,

6-

8). Because of the continuous high frequency outflow of gases, HFJV provides the surgeon with an uninterrupted surgical field and lessens the risk of aspiration of blood into the airways distal to the resection (

2). However, air trapping and barotraumas are potential risks of HFJV (

9,

10). Moreover, air trapping can cause catastrophic complication such as tension pneumothorax resulting in cardiopulmonary compromise (

10).

In our case, we chose HFJV instead of differential lung ventilation because the former hinders surgical field less than the latter. We planned to change to the latter method if we could not achieve adequate ventilation and oxygenation using the former method.

An attempt to ventilate one lung with high frequency positive pressure ventilator with a single plastic catheter was made by El-Baz et al. (

11) And simultaneous ventilation of both lungs using two separate catheters, one inserted into each main bronchus, and two ventilators, has been reported by Perera et al. (

2) However, they pointed out the flexibility of a plastic catheter could cause the difficulty with manipulation.

We applied a bronchial blocker instead of the previously used suction catheter for HFJV. Because of its stiffness, a bronchial blocker may be managed more easily and positioned more stably in the bronchus than a suction catheter, reducing the risks of hypercapnia and hypoxemia. Using this system, we were able to maintain ventilation and oxygenation, and easily and safely alternate between one and two lung ventilation without cardiopulmonary compromise.

A sterile endotracheal tube must be prepared in advance in surgical field so that it can be used immediately at any time when neither ventilation nor oxygenation is accomplished adequately using HFJV. Independent HFJV at each lung is another possible method (

2).

In conclusion, a bronchial blocker of a Univent tube may be a useful tool for HFJV of one lung during carinal resection, in that this approach may provide more convenience without the need for additional catheter to perform HFJV and more stable position of the stiffer bronchial blocker in Univent tube in airway management.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download