Abstract

Pheochromocytoma is a rare disorder and functioning tumor composed of chromaffin cells that secrete catecholamines. Patients with a pheochromocytoma 'crisis' have a high mortality in spite of aggressive therapy. We present a case with a severe acute catecholamine cardiomyopathy presenting ST segment elevation with cardiogenic shock after hemorrhage into a left suprarenal tumor. Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) support, combined with inotropic therapy, was performed. However, the patient deteriorated rapidly and was unresponsive to a full dose of inotropics and IABP. We decided to apply extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) device for the patient. His clinical state began to improve 3 days after ECMO. After achieving hemodynamic stabilization, he underwent successful laparoscopic left adrenalectomy. He needed no further cardiac medication after discharge.

Pheochromocytoma is a rare disorder and functioning tumor composed of chromaffin cell that secrete catecholamines, affecting one in a million people per year. Eighty-five percent are found in the medullae of the adrenal glands, but they may also occur in the extra-adrenal, paraganglia. Patients with a pheochromocytoma 'crisis' have high mortality, mostly from a cardiovascular origin, in spite of aggressive therapy.

We present an unusual case of a severe acute catecholamine cardiomyopathy presenting ST segment elevation with cardiogenic shock after hemorrhage into a left adrenal tumor. Medically unresponsive shock was successfully treated with multiple invasive strategies.

A 43-yr-old man presented with acute severe chest pain, shortness of breath, and dyspnea. Three year before, he had an episodic hypertensive crisis with chest discomfort and was diagnosed with pheochromocytoma. He had already severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction (ejection fraction 27%, end-diastolic/end-systolic dimension 59/48 mm) due to suspicious catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy. He was recommended to receive operation for the tumor but refused appropriate treatment without follow-up. He did not smoke and had no other risk factors for coronary artery disease. Physical examination revealed an ill, sweaty patient, with a blood pressure of 194/115 mmHg and a heart rate of 117 bpm. Initial cardiopulmonary examination revealed elevated jugular venous engorgement, and chest radiography showed signs of pulmonary edema. Echocardiography (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia, rate of 110 bpm, and significant ST depressions in II, III, AVF, V4-6 (Fig. 1A). He was treated with aspirin, intravenous (IV) nitrate, and heparin. Several minutes later, suddenly, he developed loss of consciousness with supraventricular tachycardia on repeated ECG, coinciding with extreme hypotension (71/undeterminable mmHg). DC cardioversion and tracheal intubation was performed immediately. Blood pressure did not restored after cardioversion with aggressive intravenous fluid therapy and ECG turned into ST elevation with tachycardia in the precordial leads (Fig. 1B). Cardiac enzyme showed myocardial damage; creatine kinase (CK) 667 IU/L (normal <250), CK-MB 34.6 ng/mL (normal <5), and myoglobin 1,462 ng/mL (normal <110) (Fig. 2). Echocardiography showed global hypokinesia, especially more hypokinetic in anterior and antero-septal wall in left ventricle (LV). The left ventricular ejection fraction was markedly decreased less than 35% with increased wall thickness (interventricular septal wall/posterior wall thickness 16/15 mm). Under the tentative diagnosis of acute myocandial infarction (AMI), emergent coronary angiogram was performed despite of known pheochromocytoma. Coronary angiographic finding is normal (Fig. 3) and an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was immediately inserted for hemodynamic support. He was admitted to the coronary care unit (CCU), and mechanical ventilation and inotropic agents were started (20 µg/kg/min dobutamine and 20 µg/kg/min dopamine). The urinary catecholamine levels were: norepinephrine 3,962 µg/day (normal 30-120), epinephrine 3,044 µg/day (normal 2-14), and vanilmandelic acid (VMA) 88.2 mg/day (normal <8). We considered the patient's presentation as acute decompensation on chronic catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy.

We decided to support the patient with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) because hypotension continued despite of fluid therapy, IV inotropics, and IABP. Femoral cannulation was done and assess was achieved with a percutaneous, guidewire-based technique. During ECMO, we monitored mean arterial pressure, urine output, blood lactate concentration, and central or venous mixed venous oxygen saturation in order to maintain adequate blood flow and oxygen saturation. To maximized oxygen-carrying capacity, packed red blood cells (RBCs) were transfused to achieve a hematocrit above 35% and mean arterial blood pressure was maintained between 60 and 70 mm Hg. Heparin was administrated continuously to maintain activated clotting time between 150 and 200 sec to prevent blood clotting of the ECMO circuit.

On Day 3, all inotropic support could begin to be progressively weaned, with a normal blood pressure and cardiac output. ECMO continued for 3 days maintaining cardiac output (CO) more than 3.0 L/min. Successful weaning was performed according to follow-up echocardiographic data suggestive of improve LV contractility. The IABP was removed 12 hr after the discontinuation of ECMO. There were no cannulation-related complications and major bleedings when ECMO system removed. Mechanical ventilation was required for a total of 5 days (Fig. 4).

A repeated echocardiographic examination performed by the same physician 5 days after admission to CCU revealed a vigorous ventricular contraction with normal LV systolic function (EF 66%, end-diastolic/end-systolic dimension 49/35 mm). Furthermore, laboratory findings and ECG abnormality had completely resolved.

Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) confirmed the presence of a left suprarenal mass of 4 cm, with a central hypodense region suggestive of necrosis and it was no interval change compared with previous CT (3 yr before) (Fig. 5). After 8 weeks of therapy with alpha and beta blockers (doxazocin 4 mg bid and carvediol 12.5 mg qd, respectively), the patient was sent to elective laparoscopic left adrenalectomy where an about 4.2×3.5×3 cm tumor was removed, which was proven to be pheochromocytoma (Fig. 6). The patient was discharged uneventfully without cardiac medication seven days after surgery. A follow-up ECG obtained 3 months after the first one showed complete resolution of the ST segment and T inversion (Fig. 7).

Pheochromocytomas are rare neoplasms of chromaffin tissue derived from the embryonic neural crest and produce their distant effects by secretion of excessive amount of catecholamines (1). The classic, clinical presentations of pheochromocytoma, such as headache, sweating attacks, tachycardia, and hypertension are highly sensitive and specific, but not always present (2). In addition to the classic symptoms, pheochromocytomas have been rarely presented with acute myocarditis, AMI, cardiomyopathy, or hemodynamic collapse (3).

Catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy has acute or chronic clinical forms. Acute form is associated with an excessive catecholamine surge and prone to present as acute cardiac failure, including acute pulmonary edema or cardiogenic shock (3). Especially with heart failure, patients may have very gloomy prognosis because of extensive myocardial damage (4). Chronic forms are manifested as dilated cardiomyopathy or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with or without outflow tract obstruction, leading to congestive heart failure (3, 5).

Clinical reports describing the pheochromocytoma-induced MI are rare (6). When it occurs, ECG can show ST elevation or, more commonly, non-ST elevation MI. It is not unusual for the patient with pheochromocytoma-related MI to present with acute, severe symptoms leading rapidly to death and diagnosis made at autopsy. Most of patients in these cases had no significant coronary atherosclerosis in contrast to classic MI (7). High levels of catecholamine released by the tumor can increase myocardium metabolism and cause coronary vasospasm resulting in angina, MI, and cardiomyopathy, which could be irreversible if left untreated (8-10).

In patients with pheochromocytoma, supraventricular tachycardia occurs more often than ventricular arrhythmia (11). However, ventricular tachycardia, including "torsades de pointes", or rarely ventricular fibrillation has also been described (12). The ischemia-appearing ECG changes make the diagnosis of MI confounding (13). ECG abnormalities like this may result from stimulation of the myocardium by excessively high catecholamines levels, are transient, and usually turn to normal after the removal of the tumor, which suggests a toxic myocarditis rather than true transmural infarction (14, 15). ECG in this patient showed ST depression and ST elevation, mimicking AMI, so that it was difficult to differentiate between obstructive and nonobstructive coronary lesion. We found normal coronary arteries on angiogram and increased LV wall thickness (interventricular septal wall/posterior wall, 16/15 mm) on echocardiography, which suggested catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy associated with pheochromocytoma.

Acute shock in this patient may be due to several possible causes. First, acute spontaneous hemorrhage into the tumor led to a massive release of catecholamines, which was proven on pathology. Patients with a pheochromocytoma crisis caused by spontaneous tumor necrosis or hemorrhage are exceedingly rare but their presentation can be very severe (4). Second, the clinical course of acute pulmonary edema and subsequent cardiogenic shock can be explained by the severe diffuse myocardial impairment present. Third reason for severe hypotension might be the severely reduced blood volume.

From the recovery of cardiac function from severe left ventricular dysfunction after removal of the tumor, it was the indirect evidences that the heart had exposed to long-standing high blood pressure. Hemorrhagic necrosis of the tumor led to a massive release of catecholamines, which resulted in the patient's initial hypertension and subsequent cardiogenic shock (16).

There is no reliable, controlled data regarding the treatment of adrenergic shock so far. Empiric supportive therapy counts on general principles of therapy in shock. In the literature, early detection and supportive care should be combined with treatment of underlying disease to prevent the development of irreversible multiorgan failure. Preoperative preparation with volume replacement and alpha-adrenergic blockades (usually prazocin or phenoxylbenzamine) have accounted for the most significant reductions in perioperative mortality (17).

Several preliminary clinical reports have suggested that extracorporeal circulatory resuscitation can aid in the resuscitation of patients with cardiopulmonary arrest regardless of causes (18, 19). We found only one report of successful combination of IABP and ECMO in management of acute myocarditis (20). At present, IABP, ECMO, and ventricular assist device (VAD) are available as extracorporeal support systems. IABP is convenient to be applied but can only provide limited additional CO, which usually is not adequate for all critical situations. VAD implantation is expensive and time-consuming, and not always available for some patients group. Besides, it also requires cardiopulmonary bypass for VAD setup and removal (19). In case of IABP failure supporting the patient, ECMO immediately provides adequate perfusion to all organs irrespective of lung condition. It can be started within 30 min at bedside and can take over the functions of both ventricles and lungs. Furthermore, it can support the failing heart for long term as needed and is easy to be removed at bedside in the intensive care unit. It also allows several hours or days to try weaning ECMO if the bridging tube is added to the circuit. It is reasonable to choose ECMO to treat cardiomyopathy with shock that can usually improve within 1 or 2 weeks (19). Catastrophic shock can be completely reversible without leading to further damage after its recovery from the acute phase, if ECMO can be provided in time and long enough for the recovery of myocardium.

We conclude that a catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy in patients with a pheochromocytoma seems to be completely reversible and potentially cured by timely adequate treatment. If not, an acute catecholamine crisis may be fatal. Thus, if acute cardiogenic shock in patients with a pheochromocytoma is unresponsive despite intensive medical treatment, immediate mechanical support using IABP and PCPS (percutaneous cardiopulmonary support) should be considered as a very useful therapeutic choice alongside the classic therapy of α- and β-adrenergic antagonist. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy has become the procedure of choice for most patients, with open adrenalectomy generally reserved for large tumors or those most likely to be malignant (21).

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Initial ECG at emergency room showed left ventricular hypertrophy and ST depression in precordial leads. (B) Follow-up ECG showed ST elevation when abrupt hypotension occurred.

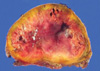

Fig. 3

Coronary angiography shows near-normal coronary artery. (A) Right coronary artery and (B) Left coronary arteries.

Fig. 4

The graph shows the typical hemodynamic pattern of an acute cardiac events: a low SBP with the need for aggressive inotropic support and with good response to inotrophic agents. IABP and ECMO support and fluid therapy restored cardiac output during the first three days. Continuous cardiogenic shock was treated with dobutamine and norepinephrine temporarily. Continuous inotropic agents were discontinued at day 5.

IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump, ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Fig. 5

(A) Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan shows multiple sepated and well-encapsulated mass with intratumoral hemorrhage. (B) Three years later CT showed an enhanced 4.2×3.5 ×3 cm sized mass with septated central necrosis (comparison between 2002 and 2005, arrows indicate tumors).

References

2. Plouin PF, Degoulet P, Tugayé A, Ducrocq MB, Ménard J. [Screening for phaeochromocytoma: in which hypertensive patients? A semiological study of 2585 patients, including 11 with phaeochromocytoma (author's transl). Nouv Presse Med. 1981. 10:869–872.

3. Schifferdecker B, Kodali D, Hausner E, Aragam J. Adrenergic shock-an overlooked clinical entity? Cardiol Rev. 2005. 13:69–72.

4. Sardesai SH, Mourant AJ, Sivathandon Y, Farrow R, Gibbons DO. Phaeochromocytoma and catecholamine induced cardiomyopathy presenting as heart failure. Br Heart J. 1990. 63:234–237.

5. Huddle KR, Kalliatakis B, Skoularigis J. Pheochromocytoma associated with clinical and echocardiographic features simulating hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Chest. 1996. 109:1394–1397.

6. Gupta KK. Letter: Phaeochromocytoma and myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1975. 1:281–282.

7. Nirgiotis JG, Andrassy RJ. Pheochromocytoma and acute myocardial infarction. South Med J. 1990. 83:1478–1480.

9. Kline IK. Myocardial alterations associated with pheochromocytomas. Am J Pathol. 1961. 38:539–551.

10. Seeley E WG. The heart in endocrine disorders. Braunwald's heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 2005. 7th ed. New York: W.B. Saunders Co.;2063–2064.

.

11. Sayer WJ, Moser M, Mattingly TW. Pheochromocytoma and the abnormal electrocardiogram. Am Heart J. 1954. 48:42–53.

12. Shimizu K, Miura Y, Meguro Y, Noshio T, Ohzeki T, Kusakari T, Akama H, Watanabe T, Honma H, Imai Y. QT prolongation with torsade de pointes in pheochromocytoma. Am Heart J. 1992. 124:235–239.

13. Haas GJ, Tzagournis M, Boudoulas H. Pheochromocytoma: catecholamine-mediated electrocardiographic changes mimicking ischemia. Am Heart J. 1988. 116:1363–1365.

14. Cheng TO, Bashour TT. Striking electrocardiographic changes associated with pheochromocytoma. Masquerading as ischemic heart disease. Chest. 1976. 70:397–399.

15. McManus BM, Fleury TA, Roberts WC. Fatal catecholamine crisis in pheochromocytoma: curable cause of cardiac arrest. Am Heart J. 1981. 102:930–932.

16. Delaney JP, Paritzky AZ. Necrosis of a pheochromocytoma with shock. N Engl J Med. 1969. 280:1394–1395.

17. Duh QY. Evolving surgical management for patients with pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001. 86:1477–1479.

18. Dembitsky WP, Moreno-Cabral RJ, Adamson RM, Daily PO. Emergency resuscitation using portable extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993. 55:304–309.

19. Chen YS, Wang MJ, Chou NK, Han YY, Chiu IS, Lin FY, Chu SH, Ko WJ. Rescue for acute myocarditis with shock by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999. 68:2220–2224.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download