Abstract

We report on a case of hepatic splenosis. A 32-yr-old man underwent a splenectomy due to trauma at the age of 6. He had been diagnosed as being a chronic hepatitis B-virus carrier 16 yr prior to the surgery. The dynamic computer tomography (CT) performed due to elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein (128 ng/mL) demonstrated two hepatic nodules, which were located near the liver capsule. A nodule in Segment IVa had a slight enhancement during both the arterial and portal phases, and another nodule in Segment VI showed a slight enhancement only in the portal phases. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the mass in Segment VI showed enhanced development in the arterial phases and slight hyperintensivity to the liver parenchyma in the portal phases. These imaging findings suggested a hypervascular tumor in the liver, which could be either focal nodular hyperplasia, adenoma, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Even though these lesions were diagnosed as HCC, some of the findings were not compatible with typical HCC. On dynamic CT and MRI, all lesions showed a slight arterial enhancement and did not show early venous washout. All lesions were located near the liver capsule. These findings, along with a history of splenectomy, suggested a diagnosis of hepatic splenosis.

Splenosis represents the heterotropic autotransplantation of splenic tissue after a traumatic splenic rupture and splenectomy. Splenosis was once thought to be rare because most cases are asymptomatic and found incidentally during laparotomy for an unrelated disease or autopsy. A recent study found that splenosis is reported in up to 67% of patients with traumatic splenic rupture. Thus, splenosis is now believed to be a common condition (1).

Hepatic splenosis is a rare event. To our knowledge, ten cases have been reported in the literature (2-10). In our case, a patient with chronic hepatitis B underwent unnecessary laparotomy and was preoperatively diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Here we review the clinical characteristics and radiological features of hepatic splenosis reported in the literature.

A 32-yr-old man was referred to our hospital for further treatment after a transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) due to HCC. He had undergone a splenectomy after a motor vehicle accident at the age of 6. Furthermore, 16 yr previously, the patient was diagnosed as being a chronic hepatitis B-virus carrier, while 7 months prior he had been conservatively treated for jaundice. During a regular follow-up, a dynamic computer tomography (CT) was performed because serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels had increased to 128 ng/mL. The dynamic CT showed two hepatic nodules, which were primarily managed by TACE using adriamycin and lipiodol at other hospitals.

The patient had no significant family history of malignancy or B-viral hepatitis. Abdominal examination revealed a left paramedian scar with no palpable masses or hepatosplenomegaly. The findings from the remainder of the exam were within normal limits. The laboratory test results were within normal ranges except for aspartate aminotransferase levels, which were 45 IU/L (normal range, 13-34) and prothrombin time was 12.7 sec (normal range, 9.9-12.3). The patient's serology for hepatitis B was positive for HBsAg, anti-HBc Ab, HBeAg, and anti-HBe Ab and negative for anti-HBs Ab. Serum HBV-DNA quantitation levels were less than 0.5 pg/mL. Serum AFP was 17.29 ng/mL and serum protein induced by the absence of vitamin K (PIVKA II) was less than 10 mAU/mL.

The dynamic CT performed at other hospitals demonstrated a 2-cm and a 3-cm nodule in Segments IVa and VI, respectively. All lesions were located near the liver capsule. The lesion in Segment IVa was located in the subcapsular area of the liver parenchyma and the lesion in Segment VI appeared to grow exophatically. The lesion in Segment IVa showed a slight enhancement during both the arterial and portal phase and another lesion in Segment VI was slightly enhanced only in the portal phase (Fig. 1). Hepatic angiography showed a subtle vascular staining lesion only in Segment IVa and subsequent TACE was performed (Fig. 2A). After three weeks of TACE, a follow-up CT scan showed a relatively homogenous lipiodol uptake in the Segment IVa nodule (Fig. 2B), while the Segment IV nodule had no lipiodol uptake. The patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in our hospital to evaluate the lesion in Segment VI. The precontrast MRI showed that the lesions were low signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images (Fig. 3A, B). When analyzed using dynamic MRI, the lesion in Segment VI had enhanced arterial phases and was slightly hyperintensive to the liver parenchyma in the portal phases (Fig. 3C, D). In addition, another lesion, which was not detected in previous imaging studies, was found in the inferior tip of Segment IVb (Fig. 3E).

Though imaging studies showed atypical findings such as only slight arterial enhancement and no early venous washout, the patient's history of chronic hepatitis B and the elevated serum AFP levels during follow-up led to a diagnosis of HCC. The child classification was A, and his indocyanine green retention at 15 min was 28.4%. Even though his reserve liver function was decreased, surgical resection was thought to be possible when the anatomic locations of the hepatic lesions were considered. During the laparotomy, a 1-cm reddish brown nodule on the greater omentum was noticed, and small multiple nodules on the surface of the small bowel were further detected (Fig. 4A, B). These observations, combined with a history of splenectomy, prompted us to strongly suspect splenosis. The 3 cm hepatic nodule in Segment VI was attached to the liver capsule and showed characteristics similar to other abdominal nodules (Fig. 4C). The Segment VI and IVb lesions were excised and the frozen histological examination of these specimens was positive for splenic tissue (Fig. 4D). Because the lesion in Segment IVa was covered with a fibrous capsule, the lesion was easily detached from the liver parenchyma and an enucleation could be performed. Pathological examination of the frozen and permanently fixed sections of this lesion found that this lesion also contained splenic tissue.

HCC is one of the most common malignancies in Korea. As in the case presented in our report, hypervascular tumors found on imaging studies that are performed due to elevated serum AFP levels in patients with chronic hepatitis B could reasonably be diagnosed as HCC in an endemic area. However, some of the findings in our case are not compatible with typical HCC. On dynamic CT and MRI, all lesions showed a slight enhancement during arterial phases and did not show early venous washout during the portal phases. In our case, all three lesions were located near the pericapsular or subcapsular area. These findings, along with a history of splenectomy due to trauma, suggested a diagnosis of hepatic splenosis.

Even though the actual mechanism of occurrence remains unresolved, splenosis is considered to develop from the implantation of splenic fragments into exposed vascularized surfaces at either the time of splenic trauma or at splenectomy. The splenic implants are multiple and splenosis can occur anywhere the fragments deposit. The liver is a possible autografting site for splenic tissue.

To our knowledge, ten cases of hepatic splenosis have been reported in the literature (2-10) (Table 1). Most patients had a history of splenectomy due to traumatic splenic rupture. The mean age of these patients was 46 yr. The mean interval between splenectomy and diagnosis of hepatic splenosis was 29 yr (range, 17-46 yr). All cases were asymptomatic and were found incidentally. The mean size of the hepatic nodule was 4.3 cm. All nodules were located near the liver capsule on imaging studies, either invaginating into the liver parenchyma or growing exophytically. In seven cases, the lesion was found in the left liver, whereas in five cases, the nodule was founded in the space between the diaphragm and the surface of Segment II, growing into the liver parenchyma. These observations may be due to the fact that the space between the diaphragm and Segment II is located next to the spleen and can be easily accessed by splenic tissue during splenectomy. In addition, the chronic compression of the diaphragm might induce splenic tissues to invade the liver parenchyma. Because the findings of hepatic splenosis were non-specific except for the hypervascular nodule, hepatic splenosis was often misdiagnosed as hepatic adenoma (2, 7, 9, 10) or HCC (3, 4, 6), according to the patient's history and the accompanying liver disease. These misdiagnoses led to unnecessary explo-laparotomy in some cases (2-4, 9, 10).

Recently, superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO)-enhanced MRI has been reported as a useful tool for distinguishing hepatic splenosis from malignant hepatic masses, except in some cases of well-differentiated HCCs (5, 8). The reticuloendothelial cells, which were located in the liver and spleen, phagocytose SPIO particles and show loss of signal intensity on the T2-weighted MRI. However, malignant lesions show no signal loss because they do not contain reticuloendothelial cells. Therefore, hepatic splenosis has a loss in signal intensity on T2-weighted images after the SPIO particles were administered. Because the contrast effect for spleen after the SPIO administration is less pronounced than for liver, splenic nodules remain slightly hyperintense relative to the hypointense liver parenchyma (5). However, the most specific imaging technique of hepatic splenosis is scintigraphy using a sensitive, heat-denatured, technetium-99m (99mTc)-labeled red blood cells (7, 11). This scintigraphy may be particularly useful when overlap occurs between the liver and spleen with 99mTc-sulfur colloid scintigraphy. This is because of the increased uptake of 99mTc-labelled red blood cells (RBCs) relative to the uptake of 99mTc-sulfur colloid by the spleen.

In conclusion, hepatic splenosis should be considered if the lesion is located near the liver capsule and is found in patients with a history of splenectomy due to a traumatic rupture. SPIO-enhanced MRI can be used to rule out malignant liver neoplasms, especially in patients with chronic liver disease. Scintigraphy using 99m Tc-labelled, heat-denatured RBCs is the most specific imaging technique and can be used to confirm the diagnosis of hepatic splenosis. If necessary, percutaneous biopsies should be performed and unnecessary laparotomies should be avoided in these patients.

Figures and Tables

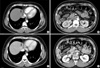

Fig. 1

Arterial phase (A, B) and portal phase (C, D) of abdominal CT scans show a 2-cm mass in Segment IVa and a 3-cm exophytic mass in Segment VI (arrows).

Fig. 2

Hepatic artery angiography shows subtle tumor staining in Segment IVa and no tumor staining in Segment VI (A). A follow-up CT scan taken three weeks later shows lipiodol uptake in the Segment IVa nodule (B).

Fig. 3

By precontrast MRI, the lesion in Segment VI shows low signal on T1-weighted (A) and high signal on T2-weighted MR images (B). Dynamic MRI shows an enhancement of the lesion during the arterial phase (C) and a slightly hyperintensive signal in the liver parenchyma during the portal phase (D). Another 1-cm hypervascular mass, which was not detected in previous imaging studies, was found in the inferior tip of Segment IVb (E).

Fig. 4

Photographs of the laparotomy show a 1-cm reddish brown nodule on the greater omentum (A) and small multiple nodules on the surface of the small bowel (B). A 3-cm hepatic nodule on Segment VI was attached to the liver capsule and shows characteristics similar to other abdominal nodules (C). The pathological examination was positive for splenic tissue (H-E stain, ×100) (D).

References

1. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 29-1995. A 65-year-old man with mediastinal Hodgkin's disease and a pelvic mass. N Engl J Med. 1995. 333:784–791.

2. Gruen DR, Gollub MJ. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking hepatic adenoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997. 168:725–726.

3. Yoshimitsu K, Aibe H, Nobe T, Ezaki T, Tomoda H, Hayashi I, Koga M. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking a liver tumor. Abdom Imaging. 1993. 18:156–158.

4. Lee JB, Ryu KW, Song TJ, Suh SO, Kim YC, Koo BH, Choi SY. Hepatic splenosis diagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002. 32:180–182.

5. De Vuysere S, Van Steenbergen W, Aerts R, Van Hauwaert H, Van Beckevoort D, Van Hoe L. Intrahepatic splenosis: imaging features. Abdom Imaging. 2000. 25:187–189.

6. Di Costanzo GG, Picciotto FP, Marsilia GM, Ascione A. Hepatic splenosis misinterpreted as hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients referred for liver transplantation: report of two cases. Liver Transpl. 2004. 10:706–709.

8. Kondo M, Okazaki H, Takai K, Nishikawa J, Ohta H, Uekusa T, Yoshida H, Tanaka K. Intrahepatic splenosis in a patient with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2004. 39:1013–1015.

9. D'Angelica M, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Isolated hepatic splenosis: first reported case. HPB Surg. 1998. 11:39–42.

10. Zhao M, Xu HW. Splenosis simulating an intrahepatic mass. Chin J Traumatol. 2004. 7:62–64.

11. Massey MD, Stevens JS. Residual spleen found on denatured red blood cell scan following negative colloid scans. J Nucl Med. 1991. 32:2286–2287.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download