Abstract

Background

Recently symptoms-based screening questionnaires have gained attention for screening for a neuropathic pain component (NePC) in various chronic pain conditions. The present study assessed the usefulness of four commonly used NePC screening questionnaires including the Self-completed douleur neuropathique 4 (S-DN4), the ID Pain, the painDETECT questionnaire (PDQ), and the Self-completed Leeds Assessment of neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (S-LANSS) questionnaire in patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) to assess the presence of NePC.

Methods

This is a single-center cross-sectional study where patients with CLBP, with or without leg pain, were included. Participants were initially screened for NePC presence by a physician according to the regular practice, and later assessed using screening questionnaires. The diagnostic accuracy of these questionnaires was compared assuming the physician-made diagnosis as the gold standard.

Results

A total of 215 patients with CLBP of which 164 (76.3%, 95% CI, 70.2-81.5) had a NePC were included. S-DN4, ID Pain, and PDQ have an area under the curve (AUC) > 0.8 indicating excellent discrimination. However, S-LANSS has an AUC of 0.69 (0.62-0.75), indicating low discrimination. S-DN4 has a significantly higher AUC as compared to ID Pain (d(AUC) = 0.063, P < 0.01) and S-LANSS (d(AUC) = 0.197, P < 0.01). But the AUC of S-DN4 does not significantly differ from that of PDQ (d(AUC) = 0.013, P = 0.62).

Conclusions

S-DN4, ID Pain, and PDQ, but not S-LANSS, have good discriminant validity to screen for NePCs in patients with CLBP. Despite using all the tests, 20-30% of patients with an NePC were missed. Thus, these questionnaires can only be used as an initial clue in screening for NePCs, but do not replace clinical judgment.

Neuropathic pain (NeP) is defined as the pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system [1]. It is distinct from nociceptive pain (NcP), which arises from actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissue leading to the activation of nociceptors [1]. Mixed pain is a combination of both NeP and NcP. NeP prevalence is rising, adversely affecting the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and posing huge financial burden [2].

In developing countries like India, pain clinics are overcrowded with patients suffering from chronic low back pain (CLBP) who are usually undermanaged. Clinical examination for the contribution of the NeP component (NePC) requires a stepwise procedure [3]. This time consuming procedure may lead to overcrowding, reducing the patient encounter time leading to undermanagement. This may also be a reason for underestimating the prevalence of the NePC in patients with CLBP [4].

To overcome this hurdle, various symptomsbased NeP screening questionnaires have been developed and validated in various chronic pain conditions [5678910]. These questionnaires got attention because of their ability to quickly (usually 5 to 8 minutes) screen patients for the presence of an NePC. The evidence regarding the usefulness of these questionnaires in various pain conditions has been previously established by various researchers [1112]. However, limited evidence is available about the usefulness of these questionnaires in patients with CLBP, which is a mixed pain syndrome. Concerns have risen regarding the underperformance of these screening questionnaires in mixed pain conditions [13]. An extensive literature search could not find any headtohead comparative usefulness study of various questionnaires in screening the NePC in patients with CLBP. Thus, the present study assessed the usefulness of four commonly used NePC screening questionnaires namely self-completed douleur neuropathique 4 (S-DN4), ID Pain, painDETECT (PDQ), and the self-completed Leeds Assessment of neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (S-LANSS) questionnaire in patients with CLBP to assess the presence of an NePC in patients with CLBP.

This is a single-centre cross-sectional study. Consecutive patients with a diagnosis of CLBP, with or without leg pain, visiting the outpatient referral pain clinic of a tertiary care hospital were screened for recruitment.

Participants were recruited from October 2014 to November 2015. Eligible patients were 18-years-old or older, of either gender, suffering from CLBP (duration of pain ≥ 3 months) and new to the clinic (they might have received treatment previously but a patient who visited the study setting for the first time was included). The patients were required to read, understand, and respond to the Hindi version of questionnaires used for the study. Patients with diabetes, cancer, or any other chronic pain condition which might hinder in the assessment of an NePC due to CLBP were excluded. Patients with incomplete data, or who were pregnant or lactating women were also excluded.

All included participants were first screened by a physician according to the regular practice. Afterwards, a trained researcher collected participants' demographic and clinical characteristics and asked the participants to self-complete the questionnaires. Later, the diagnostic accuracy of these questionnaires was assessed assuming the physician-made diagnosis as the gold standard. The researcher was kept blinded to the presence of an NePC as judged by the physician to reduce assessment bias. STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were followed while reporting the study [14]. The study proceeded after getting ethics approval from an institutional review board of PGIMER, Chandigarh, India. All patients provided written, informed consent at the time of recruitment.

The presence of an NePC was assessed using conventional physician assessment, considering it to be the gold standard. It was done according to routine clinical practice and included taking a detailed history and physical examination followed by an appropriate diagnostic workup including mapping the pain distribution, examining sensory, motor, and reflex changes, and radio-diagnostic imaging. A single physician evaluated all included patients.

Hindi versions of the following screening tools were administered to participants:

DN4 is one the most used screening tools for assessing NePCs. S-DN4 is a modified version of DN4, containing only the symptoms portion of the DN4 questionnaire, which includes both symptoms and physical exam signs. [9]. S-DN4 was developed with the aim that patients can self-complete the questionnaire without needing a physician [15]. Cross-cultural validation of the S-DN4 in the Hindi language yielded an optimal cut-off level of ≥ 3, a specificity of 88.7%, and a sensitivity of 77.5% for identifying NePCs (Submitted for publication).

The ID Pain is a self-completion questionnaire made up of 6 questions including 4 questions on the quality of pain, one on allodynia, and the other on pain distribution to the joints [8]. Cross-cultural validation of ID Pain in the Hindi language yielded an optimal cut-off level of ≥ 2, a specificity of 81.2%, and a sensitivity of 70% for identifying NePCs (Submitted for publication).

PDQ is a self-reported questionnaire consisting of 9 items including 7 Likert items on sensory symptom, one on pain course pattern, and the other on pain radiation [5]. Cross-cultural validation of PDQ in the Hindi language yielded an optimal cut-off level of > 18, a sensitivity of 82.5%, and a specificity of 91.2% for identifying NePCs (Submitted for publication).

The LANSS Pain scale is a simple tool to identify NePCs. It contains 7 items, including 5 items on symptoms and 2 items on clinical signs [7]. LANSS was modified into a self–completed version of LANSS where two clinical examination items were reworded in such a way that patients can examine themselves and answer the questions [16]. Cross-cultural validation of S-LANSS in the Hindi language yielded an optimal cut-off level of 11, a sensitivity of 75%, and a specificity of 88.7% for identifying NePCs (Submitted for publication).

Pain related functional disability was assessed using the Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (MODQ). HRQoL was assessed using a generic questionnaire EuroQoL 5D (EQ 5D).

Descriptive data is reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), numbers and percentage (%), and median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables are tested using a chi-square test and continuous variables using an independent t-test. Spearman's rank correlation is used to assess the correlation between the screening questionnaires. Receivers operating characteristic (ROC) curves for screening questionnaires are constructed to assess the diagnostic value of these questionnaires assuming a clinician made a diagnosis as the reference standard. DeLong et al. [17] suggested the method which the area under the curve (AUC) along with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the ROC curve of the screening questionnaires was calculated and compared. Discriminative statistics including concordance percentage, the kappa coefficient, sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of these questionnaires are calculated using 2 × 2 tables obtained by utilizing the cut-off levels recommended by the original developers (≥ 12 for painDETECT, ≥ 4 for DN4 and ≥ 2 for ID Pain and ≥ 12 points for S-LANSS) [5678] and cut-off levels obtained in the cross-cultural phase (≥ 3 for DN4, ≥ 2 for ID Pain, ≥ 12 for painDETECT and ≥ 11 points for S-LANSS) of these questionnaires (Submitted for publication). Two-tailed P values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis is carried out using SPSS software.

Out of the 246 patients screened, 31 were excluded, as 22 had diabetes mellitus or other chronic pain conditions, and 9 were not willing to participate. Finally, 215 were included in the present study.

The average age of study participants was 45.6 ± 13.9 years and nearly half were males. The mean duration of CLBP was high 36.2 ± 41.6 months with 64.4% of patients suffering from severe CLBP. The average NRS of back pain was 72.2 ± 16.5 points and the mean MODQ score was 48.0 ± 14.7, indicating severe disability. The average EQ-5D score was 0.268 ± 0.278 (on a -0.594 to 1 scale) (Table 1).

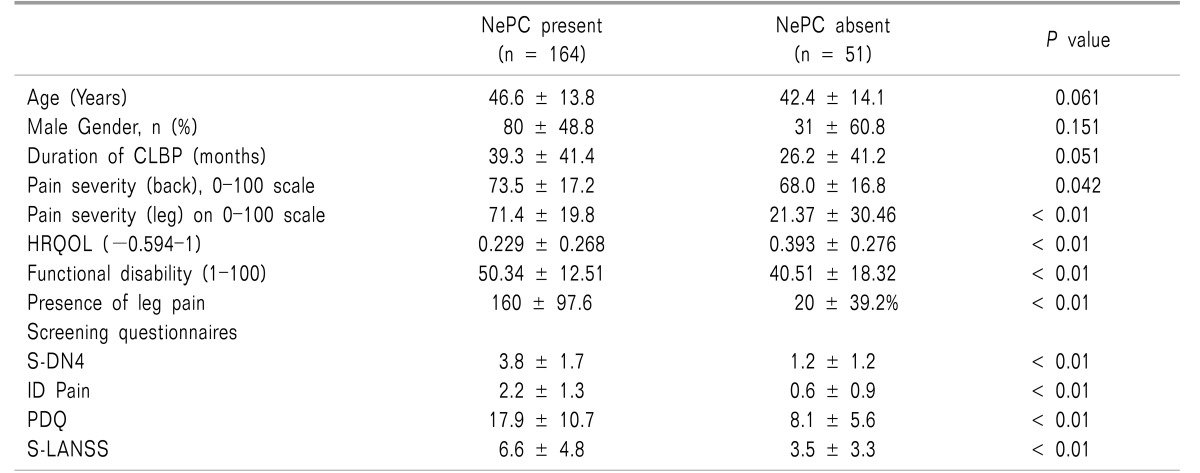

An NePC was present in 164 (76.3%, 95% CI, 70.2-81.5) patients as assessed by the physician. There was no significant difference observed in age (P = 0.061), gender (P = 0.151), and duration of disease (P = 0.051) in patients with and without an NePC. Patients with an NePC present had significantly severe pain (NRS, 73.5 ± 17.2 vs. 68.0 ± 16.8, P = 0.042), severe functional disability (MODQ: 50.3 ± 12.5 vs. 40.5 ± 18.3, P < 0.01) and a low HRQoL (0.229 vs. 0.393, P < 0.01) as compared to patients without NePC. Radiation of pain to the legs was more common in patients with an NePC as compared to patients without an NePC (97.6% (n = 160) vs. 39.2% (n = 20), P < 0.01) (Table 1).

As expected, mean scores of S-DN4, ID Pain, PDQ and S-LANSS were significantly higher in the patients in the NePC-present group as compared to the absent group (Table 1). The mean score of S-DN4 (3.8 ± 1.7 vs. 1.2 ± 1.2, P < 0.01), ID Pain (2.2 ± 1.3 vs. 0.6 ± 0.9, P < 0.01), PDQ (17.9 ± 10.7 vs. 8.1 ± 5.6, P < 0.01), and S-LANSS (6.6 ± 4.8 vs. 3.5 ± 3.3, P < 0.01) was significantly higher in the NePC-present group as compared to the absent group.

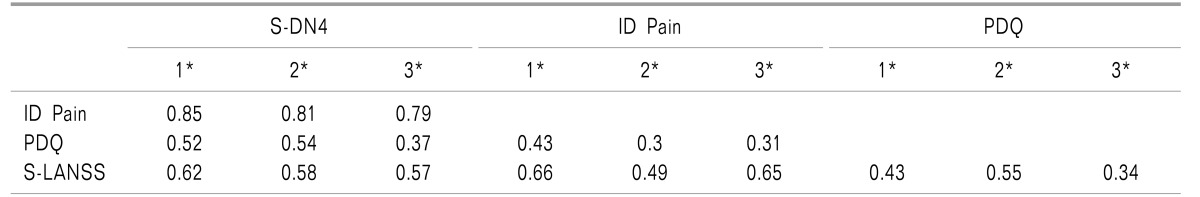

Scores of the four questionnaires in all participants were found to be positively correlated with each other (r, 0.43-0.85) (Table 2). All the correlation coefficients were found to be highly significant (for all correlation coefficients P < 0.01) and moderate to good in strength. Similar results were obtained when correlation coefficients were calculated across the subgroups according to presence or absence of an NePC.

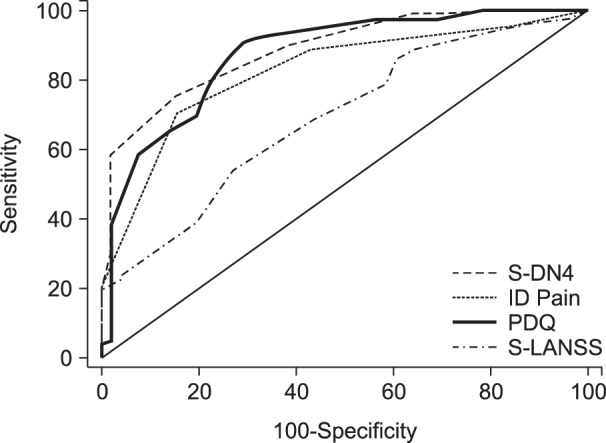

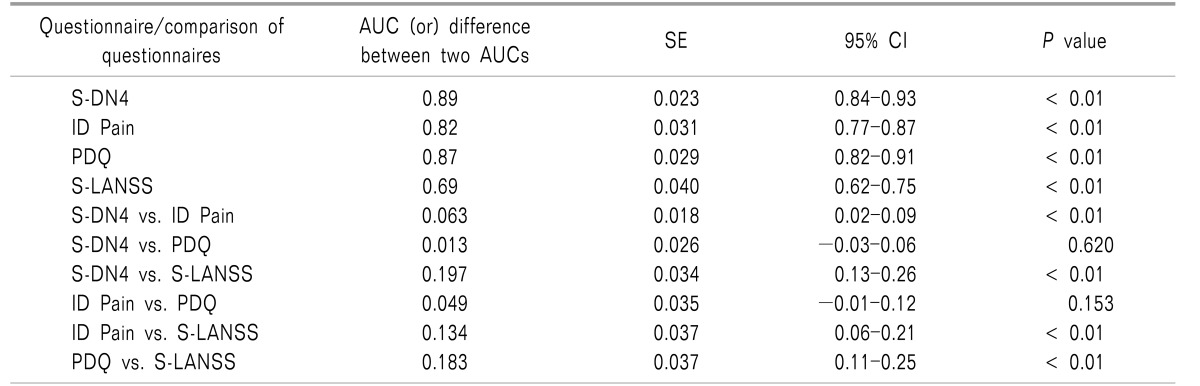

AUCs of screening questionnaires including S-DN4 (0.89 [0.84-0.93]), ID Pain (0.82 [0.77-0.87]), and PDQ (0.87 [0.82-0.91]) were high (AUC > 0.8) indicating excellent discrimination between patients with or without an NePC (Fig. 1). However, S-LANSS had an AUC of 0.69 (0.62-0.75), indicating low discrimination validity (Table 3).

When difference in discriminant validity as assessed by difference in AUC (d(AUC)) between two questionnaires was assessed, an AUC of S-DN4 was found to be comparable with PDQ (d(AUC) = 0.013, P = 0.62). However, S-DN4 had a significantly higher AUC as compared to ID Pain (d(AUC) = 0.063, P < 0.01) and S-LANSS (d(AUC) = 0.197, P < 0.01). Both ID Pain (d(AUC) = 0.134, P < 0.01) and PDQ (d(AUC) = 0.183, P < 0.01) have an AUC significantly higher than S-LANSS. The AUC between ID Pain and PDQ does not significantly differ (d(AUC) = 0.049, P = 0.153) (Table 3).

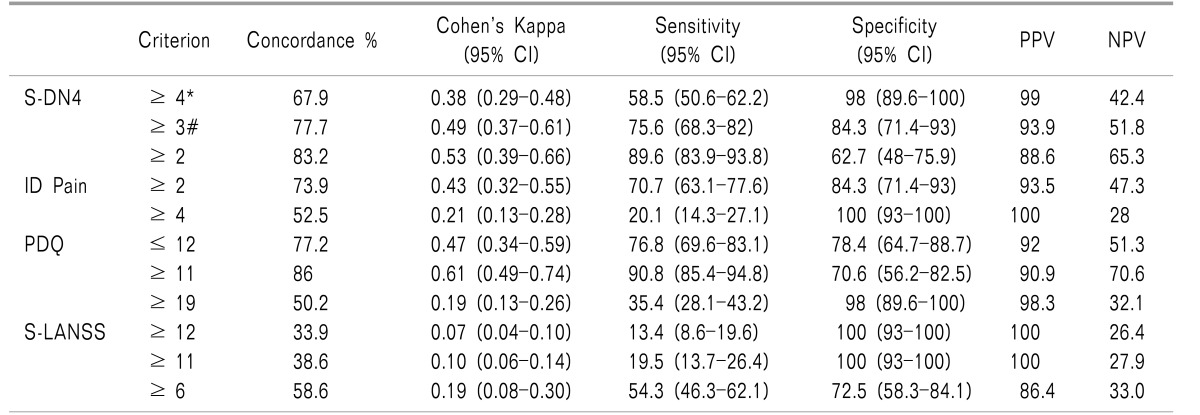

Compared to the clinician diagnosis, S-DN4 has correctly classified 67.9% of patients into the NePCpresent or absent groups at a cutoff level ≥ 4 (sensitivity 58.5%, specificity 98%) with Cohen's kappa of 0.38 indicating a fair level of agreement. At a cutoff level ≥ 3 (sensitivity 75.6%, specificity 84.3%), S-DN4 classified 77.7% of patients correctly with Cohen's kappa of 0.49 indicating a good level of agreement between the S-DN4 and the gold standard diagnosis of NePCs (Table 4).

For ID Pain, at cutoff level of ≥ 2 (sensitivity 70.7%, specificity 84.3%), it has correctly classified 73.9% of patients into NePCpresent or NePCabsent groups with Cohen's kappa 0.43 indicating a fair level of agreement between ID Pain and the clinician diagnosis. At a cutoff level ≥ 4 (sensitivity 20.1%, specificity 100%), ID Pain has correctly classified 52.5% of patients with Cohen's kappa of 0.21.

For PDQ, at a cutoff level of ≤ 12 (sensitivity 76.8%, specificity 78.4%), it has correctly classified 77.2% of patients into NePCpresent or NePCabsent groups with Cohen's kappa 0.47 indicating a fair level of agreement between PDQ and the clinician diagnosis. At a cutoff level ≥ 11 (sensitivity 90.8%, specificity 70.6%), ID Pain has correctly classified 86% of patients with Cohen's kappa of 0.61.

For S-LANSS, at cutoff level of ≥ 12 (sensitivity 13.4%, specificity 100%), it has correctly classified 33.9% of patients into NePCpresent or NePCabsent groups with Cohen's kappa 0.07 indicating a low level of agreement between PDQ and clinician diagnosis. At cutoff level ≥ 11 (sensitivity 19.5%, specificity 100%), ID Pain has correctly classified 38.6% of patients with Cohen's kappa of 0.10 (Table 4).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report assessing the comparative usefulness of S-DN4, ID Pain, PDQ, and S-LANSS for assessing the NePC in patients with CLBP in an Indian population.

As expected, CLBP patients with an NePC suffered from severe pain, severe disability, and poor HRQoL as compared to CLBP patients without an NePC. Summary scores of all four questionnaires were significantly higher in CLBP patients with NePC as compared to CLBP patients without NePC. This is expected because the symptom burden is higher in patients with an NePC and these screening questionnaires assess these symptoms. Results of the present study are in line with previous studies [1819]. Attal et al. [19] reported significantly higher DN4 scores in CLBP patients with an NePC compared to CLBP patients without an NePC.

Scores of all questionnaires are positively correlated with each other in a significant manner. Results of the present study are in line with previous studies, Padua et al. [20] reported a significant positive correlation between scores of DN4 and ID Pain questionnaires in chronic pain patients. Unal-Cevik et al. [11] reported a significant positive correlation between DN4 and LANSS. The significant positive correlation observed in the present study indicates that all questionnaires related to NePC were composed of a similar structure.

ROC curve analysis confirms that S-DN4, ID Pain, and PDQ can be reliably used to screen patients with CLBP for an NePC. However, S-LANSS failed to show reliability in screening an NePC in patients with CLBP.

In comparison to the gold standard method of diagnosis of an NePC (clinician diagnosis), S-DN4 and PDQ had the highest diagnostic accuracy, followed by ID Pain questionnaire. The observed difference between the discriminative validity of the questionnaires is due to the difference in the symptoms used and the scoring system used by each questionnaire. Although all questionnaires are largely based on a similar symptoms profile, the scoring system is different.

S-LANSS has underperformed as compared to the other questionnaires in the present study. This is because questions on the discoloration of the skin, painful to touching and rubbing were less frequently positive in NePC patients with CLBP. Responses to these questions may be more positive in chronic pain conditions like trigeminal neuralgia, postherpetic neuralgia, and other chronic pain conditions. This might be the reason that S-LANSS has shown less discriminative validity in the present study.

The advantage of using these screening questionnaires is that these questionnaires are mostly self-completed by patients, or can be administered by any healthcare professional with minimal training. These screening questionnaires can make a good impact in resource-limited settings like primary and secondary care clinics and publicly funded hospitals in developing countries.

Screening questionnaires are largely criticized due to lack of good discriminative properties [21]. However, while these screening questionnaires cannot be used for making a diagnosis, theycan be used to initially screen patients for the possible presence of an NePC. Once the screening results are positive, these subjects can undergo a further diagnostic workup according to the recommendations laid down by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) [1].

All these questionnaires are based on various symptoms that were typically seen in the patients with an NePC. Evidence shows that these screening questionnaires can be reliably used to screen an NePC in various chronic pain conditions [1618]. But conflicting evidence also exists showing the limited diagnostic value of these questionnaires in assessing an NePC in patients with widespread pain [2223]. Results of the cross-cultural validation studies showed that these scales underperform in mixed pain syndrome conditions like CLBP, neck pain and others [13].

The results of the present study showed that S-DN4, ID Pain, and PDQ have good discriminant validity to screen an NePC in patients with CLBP. At cutoff levels recommended by the original developer, and at cutoff levels ascertained from the cross-cultural validation phase, S-DN4, ID Pain, and PDQ have acceptable sensitivity and specificity. In spite of this, about 20-30% of patients with an NePC were missed and 20-30% patients were misclassified into the NePC group. This shows that these questionnaires can be used only as an initial clue for physicians to screen for NePCs, but do not replace clinical judgment.

The major strength of the present study is the use of the gold standard method for diagnosing NePCs i.e., physician-made diagnosis. A single physician diagnosed NeP, which reduced inter-observer bias. A researcher who assessed the presence of NePC using screening questionnaires was blinded to the judgment provided by the diagnosing physician. This is the first study to compare the self-reported versions of four screening questionnaires for assessing NePCs in patients with CLBP.

The present study was conducted at the referral pain clinic of a tertiary care hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the results, since the type of patients utilizing a tertiary care clinic are different than those of the generalcommunity level, and we assume that patients attending referral clinic were unable to be managed at a primary or/and secondary care healthcare setting. Thus, a higher proportion of study subjects might have severe pain with greater functional disability which may not be the same in general community settings. And the high prevalence of NePCs may be due to the recruitment of a higher proportion of patients with unmanaged pain at the initial contact with health care personnel at the referral clinic.

The questionnaires including the S-DN4, ID Pain, and S-LANSS questionnaires have not been developed to screen NePCs in patients with CLBP. PDQ is the only questionnaire which is designed especially for patients with CLBP. Although the present study supports the use of S-DN4, ID Pain, and PDQ, we also recommend considering the results with a pinch of salt because of about 20-30% were false positives and negatives.

Results of the present study showed that S-DN4, ID Pain, and PDQ, but not S-LANSS, have good discriminant validity in screening for an NePC in patients with CLBP. Despite using all these questionnaires, about 20-30% of patients with an NePC were missed and 20-30% of patients were misclassified into the NePC group. Thus, these questionnaires can be used as an initial screening strategy by physicians to screen for an NePC but do not replace clinical judgment.

References

1. Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008; 70:1630–1635. PMID: 18003941.

2. Hiyama A, Watanabe M, Katoh H, Sato M, Sakai D, Mochida J. Evaluation of quality of life and neuropathic pain in patients with low back pain using the Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire. Eur Spine J. 2015; 24:503–512. PMID: 25502001.

3. Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, Baron R, Bennett DL, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016; 157:1599–1606. PMID: 27115670.

4. Jespersen A, Amris K, Bliddal H, Andersen S, Lavik B, Janssen H, et al. Is neuropathic pain underdiagnosed in musculoskeletal pain conditions? The Danish PainDETECTive study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010; 26:2041–2045. PMID: 20597596.

5. Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006; 22:1911–1920. PMID: 17022849.

6. Bouhassira D, Attal N, Fermanian J, Alchaar H, Gautron M, Masquelier E, et al. Development and validation of the neuropathic pain symptom inventory. Pain. 2004; 108:248–257. PMID: 15030944.

7. Bennett M. The LANSS pain scale: the leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain. 2001; 92:147–157. PMID: 11323136.

8. Portenoy R. Development and testing of a neuropathic pain screening questionnaire: ID Pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006; 22:1555–1565. PMID: 16870080.

9. Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar H, Boureau F, Brochet B, Bruxelle J, et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain. 2005; 114:29–36. PMID: 15733628.

10. Scholz J, Mannion RJ, Hord DE, Griffin RS, Rawal B, Zheng H, et al. A novel tool for the assessment of pain: validation in low back pain. PLoS Med. 2009; 6:e1000047. PMID: 19360087.

11. Unal-Cevik I, Sarioglu-Ay S, Evcik D. A comparison of the DN4 and LANSS questionnaires in the assessment of neuropathic pain: validity and reliability of the Turkish version of DN4. J Pain. 2010; 11:1129–1135. PMID: 20418179.

12. Li J, Feng Y, Han J, Fan B, Wu D, Zhang D, et al. Linguistic adaptation, validation and comparison of 3 routinely used neuropathic pain questionnaires. Pain Physician. 2012; 15:179–186. PMID: 22430656.

13. Gudala K, Ghai B, Bansal D. Challenges in using symptoms based screening tools while assessing neuropathic pain component in patients with chronic low back pain. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016; 10:UL02–UL03. PMID: 27437332.

14. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014; 12:1495–1499. PMID: 25046131.

15. Spallone V, Morganti R, D'Amato C, Greco C, Cacciotti L, Marfia GA. Validation of DN4 as a screening tool for neuropathic pain in painful diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabet Med. 2012; 29:578–585. PMID: 22023377.

16. Bennett MI, Smith BH, Torrance N, Potter J. The S-LANSS score for identifying pain of predominantly neuropathic origin: validation for use in clinical and postal research. J Pain. 2005; 6:149–158. PMID: 15772908.

17. DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988; 44:837–845. PMID: 3203132.

18. Alkan H, Ardic F, Erdogan C, Sahin F, Sarsan A, Findikoglu G. Turkish version of the painDETECT questionnaire in the assessment of neuropathic pain: a validity and reliability study. Pain Med. 2013; 14:1933–1943. PMID: 23924395.

19. Attal N, Perrot S, Fermanian J, Bouhassira D. The neuropathic components of chronic low back pain: a prospective multicenter study using the DN4 Questionnaire. J Pain. 2011; 12:1080–1087. PMID: 21783428.

20. Padua L, Briani C, Truini A, Aprile I, Bouhassirà D, Cruccu G, et al. Consistence and discrepancy of neuropathic pain screening tools DN4 and ID-Pain. Neurol Sci. 2013; 34:373–377. PMID: 22434411.

21. Mathieson S, Maher CG, Terwee CB, Folly de Campos T, Lin CW. Neuropathic pain screening questionnaires have limited measurement properties. A systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015; 68:957–966. PMID: 25895961.

22. Gauffin J, Hankama T, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, Haanpää M. Neuropathic pain and use of painDETECT in patients with fibromyalgia: a cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2013; 13:21. PMID: 23409793.

23. Bouhassira D, Attal N. Diagnosis and assessment of neuropathic pain: the saga of clinical tools. Pain. 2011; 152:S74–S83. PMID: 21185120.

Fig. 1

Area under the curve of receiver operating characteristic curves of screening questionnaires.

Table 3

Discriminative Validity of Screening Questionnaires

AUC: Area under the curve, SE: standard error, CI: Confidence interval, S-DN4: Self-completed douleur neuropathique 4, PDQ: painDETECT, S-LANSS: self-completed Leeds Assessment of neuropathic Symptoms and Signs questionnaire. AUC and difference between two AUCs were calculated using DeLong et al. [17].

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download