Abstract

Methods

A complete review of the medical records of the two cases of Comamonas acidovorans keratitis.

Comamonas Acidovorans is an aerobic, non-fastidious, non-fermentative gram-negative bacillus in the Pseudomonas rRNA homology group III. It is generally regarded as a non-pathogenic environmental organism found in soil and water.1 However, it has been reported as the etiologic agent for nosocomial bacteremia, endocarditis, otitis and keratitis and has been isolated from sputum, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, and the pharynx.2-7 Despite these documented cases of infection, C. acidovorans is still considered as a highly unusual pathogen that is recovered rarely from clinical specimens. The reported cases of bacteremia usually occurred inthe immunocompromised patients,2,3 but there has been no reported cases of keratitis associated with immunocompromised conditions. We present herein clinical courses of the two cases of C. acidovorans keratitis in patients with immunocompromised corneas.

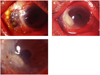

A 63-year-old man was referred to us because of necrotizing scleritis refractory to the conventional treatment with corticosteroid and amniotic membrane transplantation for 2 months. Nine months before the development of scleritis, he had received an uneventful phacoemulsification and intraocular lens insertion through a corneal incision. On his initial visit, the visual acuity was 20/60 and a large scleral melting with an overlying partial conjunctival epithelial defect was observed in his temporal sclera of the right eye (Fig. 1A). A small round opacity without epithelial defect was observed in the stroma of the previous corneal incision wound (Fig. 1A, arrow), but wound infection was not suspected initially because there was no epithelial defect. Treatment for necrotizing scleritis was started with 0.5% cyclosporine eyedrops, corticosteroids, and systemic cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor. After 7 weeks of treatment, scleritis came under control, but the patient complained of decreased visual acuity and discomfort. His vision was hand motion and there was a dense stromal infiltration from the small round stromal opacity in the wound interface. This infiltration was accompanied by an endothelial plaque and a shallow epithelial defect (Fig. 1B).

Hypopyon and vitreous opacity were also observed suggesting a combined endopthalmitis.

An anterior chamber aspirate was sent to the Microbiology laboratory for bacterial, fungal and mycobacterial cultures. Only C. acidovorans was isolated from the culture. Based on the culture results and antibiotics sensitivity test, we changed the broad-spectrum antibiotics regimen to topical ceftazidime (50 mg/ml), ciprofloxacin, and systemic ceftazidime. Ceftazidime was injected intracamerally and intravitreally. The stromal infiltration did not improve till the regimen was kept for 3 weeks. Although the deep stromal ulcer of the discrete margin and mild infiltration remained even on the regimen, the cellular reaction and hypopyon was absent and the patient noticed little pain. We thought that the infection was under control. An amniotic membrane was grafted to enhance epithelization for the deep ulcer at 5 weeks after the antibiotics change (Fig. 1C). The patient's visual acuity recovered to 20/60, and the patient's keratitis with endophthalmitis was completely cured by 7 weeks after the diagnosis of C. acidovorans keratitis.

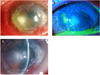

A 49-year-old man had an alkali burn in his right eye and received an uneventful penetrating keratoplasty with allograft in February 2004. Topical corticosteroid was tapered continuously during the follow-up. However, in December 2005, we noted the appearance of inferotemporal conjunctival new vessels and increased the frequency of topical 1% prednisolone acetate to four times a day and added topical 0.5% cyclosporine four times a day. He came to our clinic in May 2006 for pain and decreased visual acuity in his right eye that started 5 days ago. The vision in his right eye was hand motion, and slit-lamp examination showed a corneal epithelial defect (5.0×2.5 mm), and stromal infiltration in the graft (Fig. 2A).

After the bacterial, fungal and mycobacterial cultures were taken, topical vancomycin (31 mg/ml), amikacin (2%), moxifloxacin and systemic vancomycin/amikacin was tried empirically. After the colonies of C. acidovorans were identified, and based on the antibiotics sensitivity test, we changed the topical and systemic amikacin to ceftazidime.

Finally after 6 weeks of antibiotics treatment, the infection was controlled, but unfortunately, there was rejection of the corneal allograft (Fig. 2C). The patient's final visual acuity in his right eye was hand motion only.

Corneal wound infection after cataract extraction is a rare complication and its late onset has been known to occur after about 60 days.8 In the first case, we experienced an unusual case of keratitis involving a previous corneal wound 11 months after surgery.

C. acidovorans was isolated in both cases and the patients were receiving topical immunosuppressive agents.

We also found that they responded very slowly even to properly chosen antibiotics based on antibiotics sensitivity test, showing 7 and 6 weeks of treatment time for complete remission, respectively. Brinser and Torczynski4 first reported the C. acidovorans keratits and described that the corneal infiltration cleared slowly. Stonecipher et al5 reported 6 cases of ocular infections found to be associated with C. acidovorans. However, only one case of them was C. acidovorans keratitis associated with soft contract lens use without any other combined causable organisms. They described the treatment of the keratitis over a one-month period. In a recent report, C. acidovorans keratitis presented as a white plaque on the cornea and the patient underwent evisceration due to corneal perforation.6 Kim et al also reported C. acidovorans keratitis after soil contamination which was treated in 10 days.7 None of the previous reported cases were associated with immunocompromised state of cornea.4-7

In the first case, the initial stromal infiltration started without any epithelial defect, and in the second case, stromal infiltration increased even after complete healing of the corneal epithelium (Fig. 2B). This suggests that C. acidovorans keratitis can be involved mainly in the stroma without any manifestation of epithelial defect.

In summary, C. acidovorans can cause an indolent infection that is slowly responsive even to adequate antibiotics in immunocompromised cornea and seems to be active in the stroma without any epithelial defect. Therefore, a long term treatment is needed even with the application of the appropriate regimen based on the antibiotics sensitivity test.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Case 1 with necotizing scleritis and C. acidovorans keratitis. (A) A large scleral defect with an overlying partial epithelial defect and diffuse scleral injection was noted. A small round stromal opacity (arrow) was observed in the corneal wound that had been made 1 year before, at pre-ulcerative stage. (B) Dense stromal infiltration was noted with endothelial plaque and a shallow epithelial defect in the previous surgical wound, while in treatment of scleritis. (C) Amniotic membrane was grafted for the deep ulcer after 5 weeks of treatment because there was no decrease in stromal infiltration. Keratitis with endophthalmitis was completely cured 7 weeks after the initial diagnosis.

Fig. 2

Case 2 with C. acidovorans keratitis after penetrating keratoplasty. (A) Corneal ulceration with stromal infiltration was observed in the temporal area of previous donor cornea. (B) After 2 weeks of treatment, the epithelial defect was healed and the infiltration in corneal stroma had decreased. (C) Corneal allograft rejection developed after infection had been finally controlled.

References

1. Gilligan PH, Lum G, Vandamme P, Whittier S. Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, editors. Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas, Ralstonia, Brevundimonas, Comamonas, Delftia, Pandoraea, and Acidovorax. Manual of clinical microbiology. 2003. v. 1:8th ed. Washington: ASM press;chap. 48.

2. Castagnola E, Tasso L, Conte M, et al. Central venous catheter-related infection due to Comamonas acidovorans in a child with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Clin Infect Dis. 1994. 19:559–560.

3. Ender PT, Dooley DP, Moore RH. Vascular catheter-related Comamonas acidovorans bacteremia managed with preservation of the catheter. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996. 15:918–920.

4. Brinser JH, Torczynski E. Unusual Pseudomonas corneal ulcers. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977. 84:462–466.

5. Stonecipher KG, Jensen HG, Kastl PR, et al. Ocular infections associated with Comamonas acidovorans. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991. 112:46–49.

6. Cho BJ, Lee YB. Infectious keratitis manifesting as a white plaque on the cornea. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002. 120:1091–1093.

7. Kim JM, Kim DK, Park JM, et al. A Case of Comamonas Acidovorans Corneal Ulcer. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2005. 46:2106–2109.

8. Cosar CB, Cohen EJ, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR. Clear corneal wound infection after phacoemulsification. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001. 119:1755–1759.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download