Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the correlation between the ocular surface disease index (OSDI score) and objectively quantifiable parameters in dry eye syndrome patients, and to assess environmental and lifestyle risk factors in severe OSDI patients.

Methods

The present study was retrograde and included 30 patients (30 eyes) diagnosed with dry eye syndrome at Ilsan Paik Hospital for the first time. Shirmer's test, corneal staining, and conjunctiva staining were assessed, and tear break-up time, meibum quality, and OSDI questionnaires were performed. We measured the lipid layer thickness in tear meniscus and counted the amount of partial eyelid blinking using Lipiview®. Moreover, we modified images of the lower lid meibography and calculated the percentage of meibomian glands outside the lower tarsal plate using the ImageJ® software. We analyzed the Pearson's correlation and performed a multiple linear regression analysis between the test values and OSDI. In addition, logistic regression analysis was used to determine the risk factors of the severe OSDI group, such as insomnia, level of computer use, and exposure to fully air-conditioned indoor environments.

Results

According to the Pearson's correlation analysis, quality of the meibum showed the highest statistically significant correlation with OSDI, followed by age, conjunctiva staining score, counts of partial blinking, and corneal staining score. The multiple linear regression analysis revealed that quality of the meibum and age were statistically significant factors affecting the OSDI score. Based on the logistic regression analysis, using a computer for more than 4 hours at a time exhibited a 7.43-fold odds ratio for severe OSDI (p-value = 0.029).

Conclusions

Meibomian gland dysfunction and age should be considered to be important factors, especially in treating dry eye syndrome patients who complain severely. Moreover, we should also consider environmental factors such as long-term computer use for the treatment of dry eye syndrome patients with severe symptoms.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

LipiView® (TearScience Inc., Morrisville, NC, USA) Image. Yellow box indicates partial blinking in both eye detecting light interference reflected from lipid layer in tear meniscus.

Figure 2

Method of modifying images of the original lower lid meibographs. (A) Original meibography of left eye, captured by LipiView®. (B) Modified image of lower lid from original meibography automatically by LipiView® inset setting. (C) Image of substracted background, manually selected clear margin meibomian gland lesion, and excluded blurred-margin lesion medially and laterally from (B) image. (D) Binary modification of meibomian gland in selected lesion. W hitish lesion indicates meibomian glands.

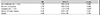

Figure 3

Ocular surface disease index (OSDI) score according to Korean dry eye syndrome (DES) guideline grade. Value in white box means OSDI average score of each group. OSDI score was not statistically in increasing trend from group 1 to 4 (p-value=0.057 > 0.05, based on Jonckheere-Terpstra test).

References

1. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the definition and classification subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Work Shop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007; 5:75–92.

2. Ahn JM, Lee SH, Rim TH, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with dry eye: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010-2011. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014; 158:1205–1214.e7.

3. Roh HC, Lee JK, Kim M, et al. Systemic comorbidities of dry eye syndrome: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey V, 2010 to 2012. Cornea. 2016; 35:187–192.

4. Paulsen AJ, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, et al. Dry eye in the beaver dam offspring study: prevalence, risk factors, and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014; 157:799–806.

5. Barabino S, Labetoulle M, Rolando M, Messmer EM. Understanding symptoms and quality of life in patients with dry eye syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2016; 14:365–376.

6. Baudouin C, Aragona P, Van Setten G, et al. Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: a clear and practical algorithm. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014; 98:1168–1176.

7. Stern ME, Beuerman RW, Fox RI, et al. The pathology of dry eye: the interaction between the ocular surface and lacrimal glands. Cornea. 1998; 17:584–589.

8. Liu H, Begley C, Chen M, et al. A link between tear instability and hyperosmolarity in dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50:3671–3679.

9. Kim DW, Kwon YA, Song SW, et al. Clinical usefulness of a thermal-massaging system for treatment of dry eye with meibomian gland dysfunction. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2013; 54:1321–1326.

10. Pflugfelder SC, Solomon A, Stern ME. The diagnosis and management of dry eye: a twenty-five–year review. Cornea. 2000; 19:644–649.

11. Hyon JY, Kim HM, Lee D, et al. Korean guidelines for the diagnosis and management of dry eye: development and validation of clinical efficacy. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2014; 28:197–206.

12. Sullivan DA, Jensen RV, Suzuki T, Richards SM. Do sex steroids exert sex-specific and/or opposite effects on gene expression in lacrimal and meibomian glands? Mol Vis. 2009; 15:1553–1572.

13. Miller KL, Walt JG, Mink DR, et al. Minimal clinically important difference for the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010; 128:94–101.

14. Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, et al. Reliability and validity of the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000; 118:615–621.

15. Lee SJ, Kim HY, Park YM, Lee JS. Comparison of therapeutic effects of 3% diquafosol tetrasodium with aging in dry eye. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2016; 57:734–741.

16. Tsubota K. Tear dynamics and dry eye. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1998; 17:565–596.

17. Chun SY, Park IK. Reliability of 4 clinical grading systems for corneal staining. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014; 157:1097–1102.

18. Yoon KC, Im SK, Kim HG, You IC. Usefulness of double vital staining with 1% fluorescein and 1% lissamine green in patients with dry eye syndrome. Cornea. 2011; 30:972–976.

19. Bron AJ, Benjamin L, Snibson GR. Meibomian gland disease. Classification and grading of lid changes. Eye (Lond). 1991; 5(Pt 4):395–411.

20. Kang DW, Eom YS, Rhim JW, et al. The effects of warm compression on eyelid temperature and lipid layer thickness of tear film. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2016; 57:876–880.

21. Moon IH, Kim TI, Seo KY, et al. The relationship between subjective ocular discomfort and blepharitis severity in dry eye patients. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2016; 57:1507–1513.

22. Baudouin C, Messmer EM, Aragona P, et al. Revisiting the vicious circle of dry eye disease: a focus on the pathophysiology of meibomian gland dysfunction. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016; 100:300–306.

23. Viso E, Gude F, Rodríguez-Ares MT. The association of meibomian gland dysfunction and other common ocular diseases with dry eye: a population-based study in Spain. Cornea. 2011; 30:1–6.

24. Vehof J, Kozareva D, Hysi PG, et al. Relationship between dry eye symptoms and pain sensitivity. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013; 131:1304–1308.

25. Petrini L, Matthiesen ST, Arendt-Nielsen L. The effect of age and gender on pressure pain thresholds and suprathreshold stimuli. Perception. 2015; 44:587–596.

26. Schein OD, Muñoz B, Tielsch JM, et al. Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997; 124:723–728.

27. Yoshioka E, Yamaguchi M, Shiraishi A, et al. Influence of eyelid pressure on fluorescein staining of ocular surface in dry eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015; 160:685–692.e1.

28. Himebaugh NL, Begley CG, Bradley A, Wilkinson JA. Blinking and tear break-up during four visual tasks. Optom Vis Sci. 2009; 86:E106–E114.

29. Korb DR, Blackie CA. Meibomian gland diagnostic expressibility: correlation with dry eye symptoms and gland location. Cornea. 2008; 27:1142–1147.

30. Tomlinson A, Bron AJ, Korb DR, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the diagnosis subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52:2006–2049.

31. Lee JH, Lee W, Yoon JH, et al. Relationship between symptoms of dry eye syndrome and occupational characteristics: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010-2012. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015; 15:147.

32. Fenga C, Aragona P, Cacciola A, et al. Meibomian gland dysfunction and ocular discomfort in video display terminal workers. Eye (Lond). 2008; 22:91–95.

33. Gayton JL. Etiology, prevalence, and treatment of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009; 3:405–412.

34. Lee AJ, Lee J, Saw SM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with dry eye symptoms: a population based study in Indonesia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002; 86:1347–1351.

35. Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000; 118:1264–1268.

36. Lee YB, Koh JW, Hyon JY, et al. Sleep deprivation reduces tear secretion and impairs the tear film. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55:3525–3531.

37. Hwang SH, Choi YH, Paik HJ, et al. Potential importance of ozone in the association between outdoor air pollution and dry eye disease in South Korea. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016; 03. 10. DOI: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0139. [Epub ahead of print].

38. Asiedu K, Kyei S, Mensah SN, et al. Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) versus the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED): a study of a nonclinical sample. Cornea. 2016; 35:175–180.

39. Asiedu K. Rasch analysis of the standard patient evaluation of eye dryness questionnaire. Eye Contact Lens. 2016; 06. 20. [Epub ahead of print].

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download