Abstract

Cardiac calcification usually occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease. However, rapid progression of cardiac calcification is rarely associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism of end-stage renal disease. We report a patient with end-stage renal disease who showed moderate left ventricular hypertrophy at the first echocardiography, and showed severe myocardial calcification and severe mitral valve stenosis 4 years later. We suspected a rapid progression 'porcelain heart' cardiomyopathy secondary to hyperparathyroidism of end-stage renal disease. The patient underwent parathyroidectomy, and considered mitral valve replacement.

Cardiovascular system disease is accountable for about half of all deaths in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Certain factors have been proposed to contribute to this exceptionally increased risk, including dyslipidemia, hyperhomocysteinemia, oxidative stress of uremia, hemodialysis, hyperphosphatemia and hyperparathyroidism. Most of all, abnormal metabolism of calcium, phosphorus and secondary hyperparathyroidism in ESRD is thought to account for heart structure calcification. Especially, patients with ESRD treated by hemodialysis have frequent and progressive vascular calcification.1)

Furthermore, extensive myocardial calcification, "porcelain heart" is uncommonly associated with hyperparathyroidism, and is usually associated with various other complications including arrhythmia, heart failure, valvular dysfunction, coronary artery disease and sudden cardiac death.2-5)

We experienced rapid progression 'porcelain heart' cardiomyopathy secondary to hyperparathyroidism of end-stage renal disease. Here, we report our case with a review of the literature.

A 34-year-old female patient with ESRD caused by hypertension was admitted to our hospital for hemodialysis to be replaced with peritoneal dialysis due to decreased adequacy. On admission, she presented with chest discomfort, exertional dyspnea of New York Heart Association class II and general weakness. In the patient's past medical history, the patient began peritoneal dialysis 10 years ago and changed into hemodialysis because of frequent dialysis catheter infections 6 years ago. The patient visited our emergency department presenting with cardiac arrest due to hyperkalemia and received an echocardiography 4 years ago. There were no unusual findings except moderate left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in the echocardiograph. Two years ago, the patient visited our emergency department again presenting with chest pain and had a coronary angiography performed. The coronary angiography revealed the right coronary artery (RCA) with 50% stenosis. Laboratory data showed hyperphosphatemia but was left untreated. She was discharged from the hospital after medical treatments and then had hemodialysis in a local hospital.

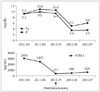

The patient's vital signs on the day of admission revealed a blood pressure of 150/70 mmHg, heart rate 110 bpm, respiration rate 20 times per minute. From physical examination, a diastolic murmur was noted at cardiac apex. A chest X-ray demonstrated mild cardiomegaly. Review of serial chest radiographs revealed progressive cardiac enlargement. An electrocardiogram showed LVH, tall-T wave in V1-4 leads. Laboratory data showed serum calcium 9.2 mg/dL (normal 8.5-10.5 mg/dL), serum phosphate 9.4 mg/dL (normal 2.7-4.5 mg/dL), serum blood urea nitrogen 135.7 mg/dL (normal 5-23 mg/dL), serum creatinine 13.5 mg/dL (normal 0.4-1.2 mg/dL), serum potassium 6.7 mg/dL (normal 3.5-5.5 mg/dL), immuno-reactive parathyroid hormone (iPTH) 2959 pg/mL (normal 10-65 pg/mL). The echocardiogram showed extensive myocardial calcification, severe mitral stenosis with a mitral valve area of 0.99 cm2 by planimetry and mean pressure gradient 24.3 mmHg. The mitral valve was severely calcified (Fig. 1). The aortic valve was thickened and had mild calcification. The left ventricular ejection fraction was estimated to be 61% and diastolic dysfunction showed as an impaired relaxation pattern. Coronary computed tomography (CT) showed severe calcification of the coronary artery and left ventricular myocardium and an increased calcium score in the coronary artery (Fig. 2). A follow-up coronary angiography was performed, and revealed remnant RCA stenosis, and left anterior descending artery with 50% stenosis. We suspected 'porcelain heart' cardiomyopathy secondary to hyperparathyroidism of ESRD. The patient started a phosphate restricted diet. A thyroid sonogram showed enlarged parathyroid glands (right lower lobe 2.2 cm size, left lower lobe 1 cm size) and the patient underwent surgical parathyroidectomy. Microscopic analysis of the parathyroid tissue showed diffuse hyperplasia of chief cells (Fig. 3). Post-operation laboratory data showed serum calcium 8.2 mg/dL (normal 8.5-10.5 mg/dL), serum phosphate 3.6 mg/dL (normal 2.7-4.5 mg/dL), iPTH 357 pg/mL (normal 10-65 pg/mL). After surgery, test results have shown improvement of Calcium, Phosphate, and iPTH levels (Fig. 4). However, the patient's cardiac symptoms remained. In the future, we will consider mitral valve replacement.

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is a common and serious consequence of ESRD. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is characterized by parathyroid hyperplasia, persistently elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels, and systemic mineral and bone abnormalities.6) Abnormal calcium and phosphate metabolism in ESRD is thought to account for the majority of heart structure calcification.7) The prevalence of such soft-tissue calcification ranges from 11% to 81% of cases. Calcification of internal viscera such as heart, lungs, stomach, and kidneys, however, is clinically more insidious.8) Cardiac calcification occurs in the coronary artery, valves, myocardium, and pericardium. In our patient, both mitral valve and myocardium, coronary artery calcification progressed rapidly. From our estimation, the reason for the rapid progression of calcification is as a result of untreated hyperphosphatemia, as well as severe secondary hyperparathyroidism of end-stage renal disease. Pathologic calcification of myocardium occurs through two basic mechanisms: Dystrophic and metastatic calcifications. Dystrophic calcification occurs in abnormal tissue, such as previous myocardial infarction, endomyocardial fibrosis, myocarditis, myocardial abscess, tuberculosis, irradiation and rare cardiac tumors.3) Metastatic calcification occurs in normal tissue in the deranged calcium phosphate metabolism, such as chronic renal failure and hyperparathyroidism.9) In this case, myocardial calcification is associated with inadequate metabolism of calcium and phosphate with subsequent calcium deposition in normal tissues. Metastatic calcification is an important complication of ESRD patients receiving maintenance dialysis. Complications of cardiac calcification include complex atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, coronary events and sudden cardiac death, with arrhythmia being the most common cause.10) Vascular calcification is common in chronic renal disease as coronary calcifications can arise from hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia, hyperparathyroidism, and hyperuremia.11) Valvular pathologies in ESRD are sclerosis and calcifications of mitral and aortic valves. Mitral annular calcification is seen in 36% and aortic valve calcification is found in 28% of ESRD patients.12) In some cases, rapid progression of valve stenosis secondary to hyperparathyroidism of end-stage renal disease was reported.13) Our case showed severe mitral calcification and mild aortic valve calcification. There is no definite therapy for this entity, but parathyroidectomy is a useful means of control, especially in those patients with very high blood levels of PTH.14)

In conclusion, our case indicates that dialysis duration and calcium-phosphate metabolisms play roles in cardiac calcification of hemodialysis patients and suggests that secondary hyperparathyroidism can cause rapid progression of cardiac calcification. Therefore, it highlights the importance of a periodic evaluation of the calcium, phosphate, PTH levels, as well as cardiac evaluations including echocardiograms, and cardiac CT scans.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Changes of transthoracic echocardiography. The echocardiogram on parasternal long axis view shows moderate LVH in 2007 (A). Follow up echocardiogram shows extensive myocardial calcification (arrowhead) and severe mitral stenosis with a mitral valve calcification (arrow) in 2011 (B, C and D). LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy, LV: left ventricle, LA: left atrium.

Fig. 2

Cardiac CT (A-D) and peripheral CT (E and F) shows extensive calcification. Cardiac CT shows severe mitral valve calcification (arrow) and myocardial calcification (arrowhead, A), diffuse calcification of LAD coronary artery (B), LCX coronary artery (C) and RCA coronary artery (D). Non enhanced CT shows muscular calcification (arrow, E) and superficial femoral artery calcification (arrows, F). LAD: left anterior descending, LCX: left circumflex, RCA: right coronary artery.

References

1. Raggi P, Boulay A, Chasan-Taber S, Amin N, Dillon M, Burke SK, Chertow GM. Cardiac calcification in adult hemodialysis patients. A link between end-stage renal disease and cardiovascular disease? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002. 39:695–701.

2. Freeman J, Dodd JD, Ridge CA, O'Neill A, McCreery C, Quinn M. "Porcelain heart" cardiomyopathy secondary to hyperparathyroidism: radiographic, echocardiographic, and cardiac CT appearances. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2010. 4:402–404.

3. Aras D, Topaloglu S, Demirkan B, Deveci B, Ozeke O, Korkmaz S. Porcelain heart: a case of massive myocardial calcification. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2006. 22:123–126.

4. Kempf AE, Momeni MG, Saremi F. Myocardial calcinosis in chronic renal failure. J Radiol Case Rep. 2009. 3:16–19.

5. London GM, Guérin AP, Marchais SJ, Métivier F, Pannier B, Adda H. Arterial media calcification in end-stage renal disease: impact on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003. 18:1731–1740.

7. Wang AY, Ho SS, Wang M, Liu EK, Ho S, Li PK, Lui SF, Sanderson JE. Cardiac valvular calcification as a marker of atherosclerosis and arterial calcification in end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005. 165:327–332.

8. Kuzela DC, Huffer WE, Conger JD, Winter SD, Hammond WS. Soft tissue calcification in chronic dialysis patients. Am J Pathol. 1977. 86:403–424.

9. Isotalo PA, Halil A, Green M, Tang A, Lach B, Veinot JP. Metastatic calcification of the cardiac conduction system with heart block: an under-reported entity in chronic renal failure patients. J Forensic Sci. 2000. 45:1335–1338.

10. Parfrey PS, Foley RN. The clinical epidemiology of cardiac disease in chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999. 10:1606–1615.

11. Moe SM, Chen NX. Mechanisms of vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008. 19:213–216.

12. Maher ER, Young G, Smyth-Walsh B, Pugh S, Curtis JR. Aortic and mitral valve calcification in patients with end-stage renal disease. Lancet. 1987. 2:875–877.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download