Abstract

We report on a 21-year-old man with fever, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. An electrocardiography showed ST elevation in multiple lead and thoracic echocardiography revealed moderate pericardial effusion. He was initially diagnosed with acute pericarditis, and treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicines with clinical and laboratory improvement. After 1 month of medication, his symptoms recurred. An echocardiography showed constrictive physiology and the patient was treated with steroid on the top of current medication. The patient had been well for 7 months until dyspnea and edema developed, when an echocardiography showed marked increased pericardial thickness and constriction. Pericardial biopsy was performed and primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma was diagnosed. Malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis of recurrent pericarditis.

Mesothelioma is a malignancy originating from the epithelial cells of the mesothelium. Primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma is an extremely rare disease with a reported incidence of 0.0022%.1) Initial presenting symptoms of this disease are dyspnea, fever and chest pain. Patients may also suffer from acute myocardial infarction or embolic stroke due to extension of tumor into myocardium or cardiac chambers. Chest X-ray may shows cardiomegaly and echocardiographic examination frequently reveals pericardial effusion. Because presenting signs and symptoms are non-specific, diagnosis of this disease is often misleading. The disease has occurred predominantly in men, with the majority of cases occurring in the fifth to seventh decades of life.2) The prognosis is dismal, even with radio- and chemotherapy.

We report a case of primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma initially presenting as acute pericarditis.

A 21-year-old man was transferred to our hospital because of cough with sputum, and dyspnea beginning 14 days prior to admission. The cough was persistent and associated with intermittent fever up to 38.3℃. The patient had been well until 2 weeks earlier, when he inoculated with influenza vaccine (H1N1). Five days before admission, he visited another hospital because of chest pain and aggravating dyspnea. Thoracic echocardiography showed large amount pericardial effusion with impending tamponade. The patient was transferred to this hospital for pericardiocentesis. On arrival in the emergency department, the patient reported fever, chills, pleuritic chest pain and orthopnea. On examination, the blood pressure was 105/78 mmHg, the pulse 97 beats per minute, and the temperature was 37.4℃. The heart rhythm was regular without murmur. Initial white blood cell count showed 11900 per microliter of which 71.6% were segmented neutrophils. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated up to 15 mg/dL. Chest X-rays revealed moderate cardiomegaly. A 12-lead electrocardiogram demonstrated regular sinus tachycardia with anterior, inferior lead ST-segment elevation. An echocardiography revealed moderate pericardial effusion (Fig. 1) and dilatation of inferior vena cava.

Emergency pericardiocentesis was performed and clear and yellowish effusion was drained. Lactate dehydrogenase of pericardial fluid was 937 IU/L, and ADA was 11 IU/L. Pericardial fluid analysis showed 900 white blood cells per microliter of which 78% were segmented neutrophils. Cytological examinations were negative for malignant cells, and cultures and smears for bacteria, acid-fast bacilli, and fungi were negative. The patient was tentatively diagnosed with viral pericarditis and given nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and colchicine. After 1 week of treatment, fever and dyspnea were subsided and an echocardiography showed minimal pericardial effusion. The patient was discharged on colchicine and NSAIDs, and followed in the outpatient department.

One month after discharge, the patient was rehospitalized because of the recurrence of chest pain and dyspnea. An echocardiography revealed increased pericardial thickness with a moderate amount of pericardial effusion with adhesion (Fig. 2). Because of increased pericardial thickness and recurrent effusion, pericardial biopsy was performed. Histopathological examination of pericardial tissue revealed chronic active inflammation and a few proliferating atypical mesothelial cells in inflamed granulation tissue.

The patient was treated with high dose prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) on the top of NSAID and colchicine. Chest computed tomography (CT) after 4 days of systemic steroid treatment revealed improved pericardial effusion with normal pericardial thickness (Fig. 3). The subjective symptoms were rapidly improved and the patient was discharged on steroids and additional NSAIDs. During the regular follow-up at outpatient department, the patient was in well being state. The prednisolone was gradually decreased to 5 mg/day with guide of hsCRP level.

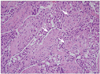

After 7 months of treatment, the patient was readmitted after complaining of general weakness, chest pain, dyspnea, and lower leg edema. Echocardiographic findings were compatible with constrictive pericarditis with marked increased pericardial thickness. A chest CT revealed diffuse increased pericardial thickening with pericardial enhancement (Fig. 4). A diagnostic pericardial biopsy was repeated, and malignant mesothelioma was diagnosed (Fig. 5).

Pericardiectomy was initially considered, but operative findings during the pericardial biopsy suggested myocardial invasion. The patient was advised to undergo palliative chemotherapy, but refused. Unfortunately, the patient died 2 months after diagnosis.

Most common symptoms of acute pericarditis are pleuritic chest pain and fever, but symptoms may vary according to underlying disease. Friction rub may have a diagnostic value, while electrocardiography and echocardiography also useful for the diagnosis. If etiology is identified, treatments according to the underlying disease are applied, although etiology of acute pericarditis cannot be identified in most of cases. In case of idiopathic acute pericarditis, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs including high-dose aspirin or ibuprofen and colchicines are the mainstay of treatment. Despite of treatment, acute pericarditis recurred on 24% of patients. Corticosteroids are treatment of option in this case.3)

Malignant mesothelioma has various symptoms but dyspnea is most common symptom.1) Because there is no pathognomonic symptom or sign in this disease, diagnosis is hard to obtain and diagnostic consideration of other disease such as idiopathic acute pericarditis or acute myocardial infarction is common. But, the possibility of this disorder may be considered in pericardial effusion and pericarditis, especially in recurrent cases.

Thomason et al.2) described 28 cases of primary pericardial mesothelioma from 1972 to 1992, and there are only 1 case of mediastinal mass on chest X-ray among 24 patients whose chest X-ray results were available. Pericardial mass on echocardiography or CT also revealed low sensitivity, which were 12% and 44%. Echocardiography has limited value when the tumor is diffusely infiltrating, rather than mass forming. Only 30% of initial cytologic examination of pericardial effusion shows malignancy. Gössinger et al.4) suggested possible role of cardiac MRI on diagnosis of mediastinal mesothelioma. Malignant mesothelioma shows high signal intensity on T2 weighted image and expresses higher signal after gadolinium enhancement on cardial MRI, and it appears to be helpful in establishing the diagnosis.5)

There are some features suggesting malignancy, which are infiltration of deep tissues, severely atypical cytoplasm and necrosis. Immunohistochemistry also provide a diagnostic clue.6)

Prognosis is very poor, with little effects of chemo- or radiotherapy. Complete resection is mandatory for cure, but diagnosis during resectable stage seldomly reported. The median survival is about 3.5 months from the diagnosis.1)

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Moderate amount of pericardial effusion with adhesion after 1 month of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicines.

References

1. Patel J, Sheppard MN. Primary malignant mesothelioma of the pericardium. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2011. 20:107–109.

2. Thomason R, Schlegel W, Lucca M, Cummings S, Lee S. Primary malignant mesothelioma of the pericardium. Case report and literature review. Tex Heart Inst J. 1994. 21:170–174.

3. Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, Sinak LJ, Hayes SN, Melduni RM, Oh JK. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010. 85:572–593.

4. Gössinger HD, Siostrzonek P, Zangeneh M, Neuhold A, Herold C, Schmoliner R, Laczkovics A, Tscholakoff D, Mösslacher H. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in a patient with pericardial mesothelioma. Am Heart J. 1988. 115:1321–1322.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download