Abstract

A primary pericardial tumor is very rare. A 77-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with chief complaint of exertional dyspnea due to large amount of pericardial effusion. She was finally diagnosed as pericardial undifferentiated carcinoma without definite histopathologial, immunochemistry feature. Despite palliative radiation therapy, the patient died of multiple organ failure. The prognosis of primary pericardial undifferentiated carcinoma is known to be very poor, especially in old people.

Primary pericardial malignant neoplasms, including mesothelioma, lymphoma, and various kinds of sarcoma, are exceedingly rare.1)2) Because of their rarity, it is very difficult to generalize about the initial clinical presentation and the clinical courses of the specific neoplasms. These tumors demonstrate aggressive behavior and extremely poor prognosis. We report a rare case of primary pericardial undifferentiated carcinoma in a 77-year-old female with initial presentation of pericardial effusion.

A 77-year-old female was admitted with effort-related chest tightness and shortness of breath for several weeks. The chest tightness occasionally radiated to the left scapular area and lasted more than half an hour. The patient had history of hypertension for 10 years. There was no family history of aortic, collagen, vascular or congenital heart disease. Vital signs were blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg, pulse rate of 70/min, respiration rate of 20 breaths/min, and body temperature of 36.5℃. On the physical examination, cardiac auscultation revealed weak heart sound and electrocardiography demonstrated non-specific depression of ST segment and T wave changes.

The blood chemistries, including coagulation studies, and lipid profiles were within normal limits. However, mild anemia (hemoglobin 9.3 mg/dL) and increased level of loctate dehydrogenase (LDH) (787 mg/dL) were noted. Cardiomegaly was noted on the chest X-ray. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed large amount of circumferential pericardial effusion with a normal ejection fraction. The size of the left ventricle and the structure of cardiac valves were normal (Fig. 1). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed a large amount of pericardial effusion with mass (Fig. 1), calcifications in the mid portion of left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, and small bilateral pleural effusion. However, the lung, thymus, esophagus were unremarkable. Abdominal CT, mammography, and gastroduodenoscopy did not indicate an extra-cardiac malignancy. Because of concern about the possibility of primary or secondary cardiac or pericardial malignant disease, we recommended pericardiostomy and biopsy. The tissue specimens yield nonspecific histopathologic finding of mild fibrosis and lymphocytic infiltrations.

After 2 months follow up in out-patient department, she complained of dyspnea again. TTE showed a 3.5×10 cm-sized inhomogeneous mass between left atrium and aortic valve area (Fig. 2). Left ventricular systolic function was normal and the evidence of hemodynamic compromise was not found. Chest CT demonstrated a 3.7×9.5 cm-sized soft tissue mass, located in transverse sinus between large vessels and upper portion of the left atrium (Fig. 2). Benign conditions like organizing hematoma, abscess, pericardial pheochromocytoma or teratoma were suspected based on the signal intensity of chest CT. She refused further invasive and non-invasive procedures to confirm the pathology of the mass.

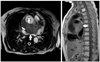

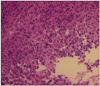

Dyspnea and chest discomfort aggravated rapidly during hospital admission. Heart rhythm was changed from normal sinus to atrial fibrillation, which might be suggestive of atrial invasion. In follow-up cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after 3 months of initial presentation, much more enlarged necrotic mass, about 8×15 cm-sized in transverse sinus, compressed right pulmonary artery, superior vena cava and ascending aorta (Fig. 3). Sternotomy was performed, but the mass was not removed successfully due to adhesion to its adjacent large vessels. Histopathologic examinations of specimen obtained during this procedure showed pleomorphic high-grade malignant tumor cells without any definite differentiation features (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemical study showed positive reactivity for vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), cytokeratin (CK), CD99 (Fig. 5), but negative reactivity for calretinin, CD56, S-100, chromogranin, synaptophysin, leukocyte common antigen (LCA). Although positive reactivity for vimentin and CD99 could suggest the possibility of high-grade sarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor, expression of epithelial differentiation markers of EMA and CK could not be explained in both tumors. Considered histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings, primary pericardial undifferentiated carcinoma was suspected. After 4 months later, TTE demonstrated significantly increased pericardial mass compared with that of before (Fig. 6). Despite several sets of palliative radiation therapy, the patient's dyspnea was not relieved and expired due to multiple organ failure just within four months after presentation.

We present an unusual case of rapidly progressive pericardial undifferentiated carcinoma. Primary cardiac tumors are rare, with an incidence of 0.02%.1) Majority of these tumors are benign, with myxoma comprising 50% of primary cardiac tumors. Malignant tumors account for 25% of primary cardiac tumors. Sarcoma is most common and accounting for 20% of primary malignant cardiac tumors. They are often poorly differentiated, making an exact histologic diagnosis difficult.2) The 2 most common types of sarcomas are angiosarcomas and undifferentiated sarcomas. Other groups include leiomyosarcomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, osteosarcomas, and fibrosarcomas. Other primary malignant neoplasms include lymphomas and mesotheliomas, but tumors metastatic to the heart are far more common than primary cardiac tumors and actually appear to be increasing in incidence because of prolonged survival of cancer patients.

Primary pericardial tumor is extremely rare, reported incidence of less than 0.0022% among 500,000 with autopsy cases.3) Pericardial malignancy can be manifested as pericarditis, pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, or pericardial constriction. Patients with primary cardiac neoplasia present with a wide range of symptoms, but the most common symptom is dyspnea. Other common symptoms are chest pain, cough and orthopnea due to heart failure, and pericardial effusion.2) The clinical presentation is determined by many factors, including tumor location, size, growth rate, and degree of invasiveness.4)

TTE or trans-esophageal echocardiography, CT, MRI, aspiration cytology of pericardial fluid, or pericardiotomy with tissue biopsy may yield diagnostic confirmation. While echocardiography may provide initial information about cardiac compression and hemodynamic status, CT and MRI adequately demonstrates the morphology, location, extent of cardiac neoplasm and possible associated extracardiac disease.5-8) Pericardiocentesis may be applied to relieve from pericardial tamponade, and often demonstrates cytological diagnosis. Recently, pericardioscopy has been employed and allows direct visualization of pericardial space, providing much more sensitivity than blind pericardial biopsy. Along with open biopsy, pericardioscopic method provides diagnosis in more than 90% of cases provided that appropriated specimens are obtained.9) The prognosis in the case of primary pericardial malignant tumor is dismal, because complete surgical resection is often impossible and radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy often yield limited outcome.10)

We report an unusual rare case of pericardial tumor with rapid progression initially presented with pericardial effusion. After 2 months progression, echocardiography and CT revealed the presence of a mass interposed between left atrium and aortic root. After 2 more months, cardiac MRI revealed that the mass was much more enlarged with necrotic center and compressed adjacent great vessels, suggestive of possible malignant feature. Histopathologic diagnosis of the tissue obtained by the sternotomy confirmed unusual undifferentiated carcinoma without any definite differentiation. Dismal progression of the patient's cardiac tumor leads her to heart failure with arrhythmia, and to death finally.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Transthoracic echocardiography (A: parasternal long axis view, and B: parasternal short axis view) revealed large amount circumferential pericardial effusion (arrows). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (C) showed a large pericardial effusion with mass (15 mm in thickness over the right ventricle and 25 mm over the left ventricle), located in transverse sinus between large vessels and upper portion of the left atrium.

Fig. 2

Transthoracic echocardiography (A: parasternal long axis view, and B: parasternal short axis view) revealed a mass (arrows) of inhomogenous echogenecity, located in juxtaaortic valve area. Contrast-enhanced chest CT (C) showed a large soft tissue mass about 3.7×9.5 cm-sized, located in transverse sinus between large vessels and upper portion of the left atrium (arrows).

Fig. 3

Follow-up T2-weighted MR image after 3 month of initial presentation showed that a huge mass (arrows) about 8×15 cm-sized, settled in transverse sinus was compressing right superior vena cava without evidence of invasion of adjacent vessels.

Fig. 4

The tumor cells revealed pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nucleus with epithelioid feature without any definite differentiation (H&E, ×400).

References

1. Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Burke AP, Green CE, Galvin JR. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000. 20:1073–1103.

2. Spodick DH. Braunwald E, Zipes DP, Libby P, editors. Pericardial disease. Heart Disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 2001. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co.;1858–1859.

3. Cohen JL. Neoplastic pericarditis. Cardiovasc Clin. 1976. 7:257–269.

4. Perchinsky MJ, Lichtenstein SV, Tyers GF. Primary cardiac tumors: forty years' experience with 71 patients. Cancer. 1997. 79:1809–1815.

5. Smith DN, Shaffer K, Patz EF. Imaging features of nonmyxomatous primary neoplasms of the heart and pericardium. Clin Imaging. 1998. 22:15–22.

6. Alam M, Rosman HS, Grullon C. Transesophageal echocardiography in evaluation of atrial masses. Angiology. 1995. 46:123–128.

7. Chaloupka JC, Fishman EK, Siegelman SS. Use of CT in the evaluation of primary cardiac tumors. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1986. 9:132–135.

8. Hur SH, Kim KS, Kim YN, Shin KM, Han SW, Kang MS, Kim KB. The characteristics of primary cardiac tumors occurred in Korean people. J Korean Soc Echocardiogr. 1995. 3:72–82.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download