Abstract

Infective endocarditis (IE) is one of the major complications of the mitral valve prolapse (MVP) syndrome and usually involves mitral valve (MV) and its accessory apparatus. Left atrial (LA) mural endocarditis is a condition of rarely diagnosed and the most feasible mechanism is related to the impact of regurgitant jet that causes endothelial damage and retrograde microorganisms dissemination. Echocardiography is essential in diagnosis and treatment of IE but in mural endocarditis, it may be difficult to find vegetation by standard view of transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). We report a case of LA mural endocarditis which was diagnosed by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) in a patient with MVP.

IE is an uncommon but life-threatening infection and one of the major complications of the MVP syndrome. Although the valve and its accessory apparatus are the most common site of infection, vegetation may occur in mural endothelium of the LA (mural endocarditis). LA mural endocarditis is a condition rarely diagnosed and may define a subpopulation at increased risk of systemic embolization.1)2) The most feasible mechanism is related to the impact of a regurgitant jet that may cause a direct injury of endothelium at its knock-on site (jet stream effect), resulting in depositions of fibrins and platelets that may serve as a nidus of bacterial growth. We report a case of LA mural endocarditis which was diagnosed by TEE in a patient with MVP.

A 38-year-old man was admitted due to evaluation of MV and possible IE. He had no significant past history and family history and was unaware of his previous heart condition. He was well until 1 month before when he experienced body aches, weakness, febrile sensation, chilling and mild dyspnea (NYHA functional class II). 2 weeks later, he visited health promotion center for evaluation of above symptoms and was referred to our cardiology department due to cardiac murmur. TTE showed mild left ventricular enlargement and trivial amount of pericardial effusion on posterior aspect of left ventricle. Eccentric mitral regurgitant jet was seen on a color Doppler test and anterior mitral leaflet was prolapsed into the LA during systole but it was difficult to exclude MV vegetation because of poor window of TTE. So he was admitted for further evaluation and treatment of MVP and/or IE.

Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, pulse rate of 76/minute, body temperature of 37.7℃ and respiratory rate of 20/minute. Heart sound was regular but grade III-IV/VI systolic murmur was heard along the left lower sternal border.

Before admission, there were no abnormalities on simple chest X-ray but chest X-ray on admission showed left pleural thickening. Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm. Initial laboratory investigations revealed elevated inflammatory markers with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 32 mm/h (reference range [RR]: 20 <mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 63.9 mg/L (RR: 5 <mg/L). Hemoglobin level was mildly decreased (10.3 g/dl, RR: 12.9-16.9 g/dl) and serum pro-B-type natriuretic peptide was borderline (262.1 pg/ml, RR: 222 <pg/ml). Microscopic hematuria (RBC 3+) was noted but creatinine level was normal. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated several gall stones and multiple low-density lesions in the spleen which were suspected to be embolic infarction.

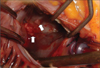

TEE was performed for further evaluation of the MV. MV was thick (4.6 mm) and myxomatous (Fig. 1). Anterior mitral leaflet showed flail movement due to rupture of chordae tendinae but vegetation was not observed on the MV. Color Doppler echocardiography showed eccentric regurgitant jet directing to the posterior wall of LA and there was large, freely moving mass (21×11.5 mm) attached to the posterior wall of LA, that is, the impact site of a regurgitant jet (Fig. 2 and 3). Consecutive 3 times blood culture examination revealed streptococci bovis. LA mural endocarditis was diagnosed and intravenous antibiotics was started. 3 days later, surgical intervention with MV replacement and resection of the vegetations was undertaken because there were several features suggesting high risk of embolism such as large vegetation size, suspected embolic infarction of spleen and highly mobile vegetations that were repeatedly struck by regurgitant jet. Intraoperative findings were thick and myxomatous MV with ruptured chordae tendinae of anterior MV and several vegetations attached to the posterior wall of LA but there were no vegetations on the MV (Fig. 4). Vegetations were mixed with coccal bacteria and fibrin clot on microscopic examination and culture of vegetation showed bacterial growth of streptococci bovis.

IE is a microbial infection of the endocardial surface of the heart and a vegetation is characteristic lesion of IE. Although heart valves are the most common site of involvement, vegetations may occur in other intracardiac locations (ventricle, atrium, mural thrombi and endothelium of great vessels).3)4) The role of echocardiography in diagnosis and treatment of IE is well known and the appropriate use of echocardiography depends on patient's clinical finding and pretest probability of IE. For patients whose pretest probability of IE is moderate or who need evaluation for prosthetic valve or non-valvular site, initial use of TEE is more cost-effective and efficient method than TTE.5)6) MVP has been described as the most common cause of nonischemic mitral regurgitation. The prognosis is usually benign but there can be serious complications such as severe mitral regurgitation, endocarditis, and sudden death.7-10) The risk of IE in MVP is threefold to eightfold higher, with an estimated incidence of about 0.02% per year. Predictors of increased risk for IE include mitral regurgitation, systolic murmur, male sex, age older than 45 years and valve thickening and redundancy. Turbulent blood flow caused by mitral regurgitation and thickened MV are believed to be the main pathological mechanisms of valvular infection.11-13) IE can be the initial presentation of MVP and although the valve is the most common site of infection, the cardiac infection need not be confined to the MV and may not even involve that valve.1)2)13) Infection involving the nonvalvular endocardium (mural endocarditis) is rarely diagnosed condition and is thought to develop in two ways. The more common is growth of a vegetation at the site of jet lesion at which the impact of regurgitant jet causes endothelial injury, resulting in depositions of fibrins and platelets and retrograde dissemination of microorganisms. Less common is primary mural endocarditis seen in chronically ill or immunodeficient patients without heart disease. In patients with MVP, eccentric mitral regurgitation is common and it might cause endothelial damage on knock-on site of left atrium and growth of vegetation.1)14)

It is important to recognize that the sensitivity and specificity of TTE for vegetation is not so high, and the absence of vegetation on TTE does not rule out the diagnosis of IE. As in this case, when IE is suspected clinically but valvular vegetation is not found on TTE, one should consider the possibility of mural endocarditis and the use of TEE for meticulous examination of other cardiovascular structures.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Transesophageal echocardiography. Anterior leaflet of mitral valve (arrow) is thickened and myxomatous and is displaced into the LA during systole. LA: left atrium, LV: left ventricle.

Fig. 2

A: Slightly modified transesophageal long axis view shows eccentric jet flow of mitral regurgitation due to mitral valve prolapse. B: Arrow point to the vegetation located on the myocardial wall of the posterior aspect of the left atrium where the jet of mitral regurgitation is directed. LA: left atrium, LV: left ventricle.

References

1. Ringer M, Feen DJ, Drapkin MS. Mitral valve prolapse: jet stream causing mural endocarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1980. 45:383–385.

2. Bierbrier GS, Novick RJ, Guiraudon C, Wisenberg G, Boughner D. Left atrial bacterial mural endocarditis. Chest. 1991. 99:757–759.

3. Shirani J, Keffler K, Gerszten E, Gbur CS, Arrowood JA. Primary left ventricular mural endocarditis diagnosed by transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1995. 8:554–556.

4. Moaref AR, Mollazadeh R, Zamirian M, Sharifkazemia MB. Rapid progression of aortic wall vegetation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008. 21:297.e1–297.e2.

5. Daniel WG, Mügge A, Grote J, Hausmann D, Nikutta P, Laas J, Lichtlen PR, Martin RP. Comparison of transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography for detection of abnormalities of prosthetic and bioprosthetic valves in the mitral and aortic positions. Am J Cardiol. 1993. 71:210–215.

7. Duren DR, Becker AE, Dunning AJ. Long-term follow-up of idiopathic mitral valve prolapse in 300 patients: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988. 114:42–47.

8. Zuppiroli A, Rinaldi M, Kramer-Fox R, Favilli S, Roman MJ, Devereux RB. Natural history of mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol. 1995. 75:1028–1032.

9. Kim MK, Song JK, Kang DH, Lee JH, Cho YH, Park KH, Ko KH, Yoon YJ, Kim JJ, Park SW, Park SJ. Recent trends and clinical outcomes of infective endocarditis. Korean J Med. 2000. 58:28–38.

10. Avierinos JF, Gersh BJ, Melton LJ III, Bailey KR, Shub C, Nishimura RA, Tajik AJ, Enriquez-Sarano M. Natural history of asymptomatic mitral valve prolapse in the community. Circulation. 2002. 106:1355–1361.

11. Clemens JD, Horwitz RI, Jaffe CC, Feinstein AR, Stanton BF. A controlled evaluation of the risk of bacterial endocarditis in persons with mitral-valve prolapse. N Engl J Med. 1982. 307:776–781.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download