Abstract

Cornelia de Lange syndrome is a congenital disease, basically characterized by psychomotor retardation associated with a series of malformations, including mainly skeletal, craniofacial deformities together with gastrointestinal and cardiac malformations. There is no definitive biochemical or chromosomal marker for the prenatal diagnosis of this syndrome. We actually want to present the case of a 10-year-old patient, who was admitted to our clinic for dental pain. The patient had the symptoms of Cornelia de Lange syndrome. During the oral examination of this patient, the patient was found to have the typical symptoms of Cornelia de Lange syndrome, such as micrognathia and delayed eruption in conjunction with the symptoms of the Hutchinson's syndrome, which had never been reported before.

Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CDLS), first described in its full clinical presentation by Dr. Cornelia de Lange in 1933,1-4 is a multisystem syndrome involving congenital malformations, growth retardation and neurodevelopmental delay. Formerly, Brachmann in 19161-3 had observed a child at autopsy with similar features as well as additional findings of upper limb deficiencies. For the reason of their contributions, both Brachmann's and de Lange's names have been attached to the name of this syndrome.1-3

This syndrome is a rare malformation and retardation syndrome of unknown etiology. It has characteristic abnormalities, including microcephaly, growth failure, anomalies of development of the hands and feet, short stature, excessive growth of hair, heavy eyebrows, synophrys (growth of eyebrows across the midline to form one large confluent eyebrow), long eyelashes, strabismus, small nose with anteverted nares, long philtrum, micrognathia, downturned mouth, hypoplastic nipples and umbilicus, flexion contracture of elbows, micromelia and hirsutism. The clinical diagnosis of this syndrome is based mainly on a group of these features.1,3-7 Most cases are sporadic, although autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance has been suggested. Severe growth and mental retardation are common. The list of the head and oral manifestations are presented in Table 1.

The diagnosis of the syndrome is based solely on the clinical grounds; there are no biochemical or chromosomal markers for CDLS yet. This lack of biological markers makes determination of its incidence difficult.6 The duplication or partial trisomy of chromosome 3 has been pointed out as a probable cause of this syndrome, and dominant inheritance is most likely involved.8

The patients are usually uncooperative due to their mental retardation. Hyperactive behaviour, autism and neurosensory auditory disorders are common.9,10 The course is usually marked by initial hypertonicity, low-pitched weak cry, malnutrition and behavioral problems, with marked mental deficiency. In classical cases there is rarely any difficulty in making the diagnosis, but in mildly affected cases, it may be difficult to feel sure about the diagnosis.1

In this particular instance, we did have a 10-year-old male patient with developmental disorder and speech impediment, who came to our office for dental pain. Initially, we noted that our patient was the son of a 29-year-old mother with a history of premature births. The male baby weighed about 2,000 g when he was born. He had also suffered malnutrition and bronchopneumonia and he had received the proper treatment during the first three months after delivery. We also recorded that our 10-year-old patient had been unable to talk and walk until he was 2.5 years old. The parents of this patient are biologically related and their first-born child died actually only 6 months after the birth. The cause of the death was pneumonia. We also learned that our patient had quite a healthy sister.

During the physical examination of the patient, we recorded this data as follows:

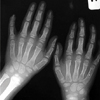

His face seemed dysmorphic; he had thick and curly hair eyebrows meeting at the midline, and he had long and curved eyelashes (Fig. 1). His ears were abnormally low placed, they were dysplastic, and his mandibular symphysis was bumpy. He also had anteverted nostrils, a small nose, thin lips with the downward turned angles of the mouth, micrognathia, short neck, fairly small feet and hands, the 5th finger with bilateral clinodactyly and some fusiform like fingers, bilateral micromelia on his 4th and 5th toes, hypogonadism and some hirsutism on his arms and legs. When we got the X-ray examination of the patient, we found clinodactyly on the right 4-5th toes, on the left 2-3rd toes and on the 5th finger (Figs. 2 and 3).

The chromosome analysis from the peripheral blood of the patient was performed showing a normal karyotype (46, XY). The patient scored 55 on the intelligence quotient (IQ) test, which fell into the interval of 44-75. He did not have the muscular capacity that a 10-year-old should have nor could communicate. The patient was only able to understand the basic words and some phrases. During evaluation of the heart of the patient, the echocardiography parameters were found to be normal. We did, however, found a chest deformation (pectus excavatus), and the patient did have some rashes and skin marks on his white-pale skin. His back was short, with the hairline being low, and he also had the hypoplastic nipple and umbilicus. He had cutis marmaratus and hirsutism on the back (Fig. 4). We found that a low-pitched cry was frequently noted.

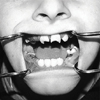

During the oral examination of the patient, we found micrognathia and delayed eruption. The upper lateral teeth, upper right canine and lower canines had not been erupted. In addition, we found an unusual finding consistent with a lot of decay and cavities on the upper central teeth, which was similar to the Hutchinson's syndrome. This trait has not been previously described in CDLS (Fig. 5).

Based on our findings, we performed a general anesthesia in order to extract the teeth that had initially been diagnosed with the extraction indications without any treatment. There were no complications throughout the anesthesia and/or intubation process. Furthermore, we confirmed that there were no complications during the postoperative period.

Cornelia de Lange or Brachmann de Lange syndrome is a rare congenital disorder of unknown aetiology. The possibility of diagnosing this syndrome at birth is about 1 out of 40,000.9 This syndrome is related to mental retardation, skeletal defects (including brachycephaly, hypoplastic mandible and cleft palate), ocular defects, epilepsy and varying degrees of hirsutism. The eye brows may be joined across the bridge of the nose (synophrys) in addition to hypertelorism and antimongoloid slant of the eyes, upward-facing nostrils, and thin lips, which made us become aware of the CDLS.5,9,11,12 In our opinion, the patient presents the typical facial characteristics of CDLS.

For our diagnosis process, the most essential diagnostic parameters seem to have been observed in respect of the face and limbs. The hypertrichosis and facial features concerning the long philtrum, thin lips and downturned angles of the mouth, anteverted nostrils and micrognathia are usually noted even in mildly affected, fair complexioned children. Based on the supportive, mild limb findings, such as small hands and feet, proximally placed thumbs, single palmar creases and limitation of the elbow extension, diagnosis is usually possible with a reasonable margin of error.2,11 The gastroesophageal reflux and sensorineural hearing loss are also common complications of the condition.4,13 CDLS is generally accepted as being characterized by mental retardation associated with a characteristic group of physical malformations. Most cases described include severely deformed structures, although many of the physical manifestations may be present in members of a normal population. The presence of severe subnormalities has usually been a major factor in making this diagnosis.10,14

Diagnosis and counseling for the CDLS is complicated by the phenotypic variability and lack of a definitive diagnostic marker. Although most cases appear to be sporadic, several families have been reported to demonstrate autosomal dominant inheritance.15 The clinical phenotype has been shown to be quite variable. The full phenotypic spectrum will not be evaluated until the gene is identified and a possibility of molecular confirmation of the diagnosis appears.13,15

Some dental abnormalities reported earlier include delayed eruption, spacing and macro- or microdontia.12 Yamamoto et al.,7 have reported two cases with delayed tooth eruption and microdontia, with one of these cases being a partial anadontia. In our case, we have found micrognathia and delayed eruption. Unfortunately, we were unable to take orthopantomograph, because the patient did not co-operate, nor we could measure microdontia, because of many decayed teeth and the eruption being incomplete. The upper and lower permanent first molars and deciduous molars had to be also extracted due to excessive caries. More distinctively, as compared to the previous cases, in our case we have pinpointed a formation, like Hutchinson's teeth, on the upper central teeth.

Also, there may be cardiovascular, endocrine and gastrointestinal abnormalities. Barret et al.,12 reported a case of de Lange syndrome, which posed some difficulties in terms of tooth extraction and a hemorrhagic diathesis thought to be due to a variant of von Willebrand's disease. In our case, there has been no such a hemorrhagic complication.

As a presentation of different types of CDLS; Van Allen et al.16 proposed a classification system. Type I 'classic' patients have the characteristic facial and skeletal changes of CDLS. Type II 'mild' CDLS patients have similar facial and minor skeletal abnormalities that were noted in type I; however, these changes may develop later or may be partially expressed. Type III 'phenocopies' CDLS includes the patients who have phenotypic manifestations of CDLS, which are causally related to chromosomal aneuploidies or teratogenic exposures. Based on the given classification, our case falls into type II.

When Braddock et al.1 radiologically evaluated these both types, classic and mild, in 21 CDLS patients, they reported the cases with the following ratio(s) respectively: microcephaly with the chance of 75%, mandibular spur with the chance of 42%, distal limb defect with the chance of 89%, dislocated/hypoplastic radial head with the chance of 79% and short sternum with precocious fusion with the chance of 54%, and they also indicated that the radiological diagnosis was possible. Our case employed the radiological diagnosis only for the graphy of the hands and feet.

Zankl et al.,13 have reported a patient with mild CDLS and unusual findings of the asymmetric growth of one body half and irregularly shaped pigmentary anomalies of the skin. They have suggested that this phenotype could be the result of the mosaicism mutation or that of the submicroscopic deletion affecting one or more putative CDLS gene(s).

Brylewski,10 has reported that the large majority of such patients have the IQ below 50. Only 15 patients had the IQ of 50 or above. Of those 15 patients, only five of them were 2 years old or younger. Only two patients with de Lange's syndrome have been reported as having intelligence within the normal limits. In our case, the patient scored 55 on the IQ test, which fell into the interval of 44-75.

Once it has been researched, we have realized that there were only a few citations on the dental and oral findings of the Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Since the literature regarding the CDLS was not so informative, it appears that the relationship between the oral manifestations of this syndrome and other syndromes must be further investigated.

In conclusion, all the findings in this study may lead us to believe that there is a possible connection between the symptoms of CDLS and the Hutchinson's syndrome. We strongly recommend that the existence of such a relationship should be investigated in the future.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Braddock SR, Lachman RS, Stoppenhagen CC, Carey JC, Ireland M, Moeschler JB, et al. Radiological features in Brachmann-de Lange syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1993. 47:1006–1013.

2. Jackson L, Kline AD, Barr MA, Koch S. de Lange syndrome: a clinical review of 310 individuals. Am J Med Genet. 1993. 47:940–946.

3. Huang WH, Porto M. Abnormal first-trimester fetal nuchal translucency and Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2002. 99:956–958.

4. Sakai Y, Watanabe T, Kaga K. Auditory brainstem responses and usefulness of hearing aids in hearing impaired children with Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002. 66:63–69.

5. Grau Carbó J, López Jiménez J, Gimenéz Prats MJ, Sànchez Molins M. Cornelia de Lange syndrome: a case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007. 12:E445–E448.

6. Sarimski K. Analysis of intentional communication in severely handicapped children with Cornelia-de-Lange syndrome. J Commun Disord. 2002. 35:483–500.

7. Yamamoto K, Horiuchi K, Uemura K, Shohara E, Okada Y, Sugimura M. Cornelia de Lange syndrome with cleft palate. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987. 16:484–491.

8. Corsini LM, De Stefano G, Porras MC, Galindo S, Palencia J. Anaesthetic implications of Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth. 1998. 8:159–161.

9. Aitken DA, Ireland M, Berry E, Crossley JA, Macri JN, Burn J, et al. Second-trimester pregnancy associated plasma protein-A levels are reduced in Cornelia de Lange syndrome pregnancies. Prenat Diagn. 1999. 19:706–710.

11. Allanson JE, Hennekam RC, Ireland M. De Lange syndrome: subjective and objective comparison of the classical and mild phenotypes. J Med Genet. 1997. 34:645–650.

12. Barrett AW, Griffiths MJ, Scully C. The de Lange syndrome in association with a bleeding tendency: oral surgical implications. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993. 22:171–172.

13. Zankl A, Rampa A, Schinzel A. Brachmann-de Lange syndrome (BDLS) with asymmetry and skin pigmentary anomalies: a result of mosaicism for a putative BDLS gene mutation? Am J Med Genet A. 2003. 118A:358–361.

14. Kline AD, Barr M, Jackson LG. Growth manifestations in the Brachmann-de Lange syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1993. 47:1042–1049.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download