Abstract

Objective

We investigated the structural differences in the pelvic bone architecture of Korean women and their association with the mode of delivery by performing computed tomography (CT) pelvimetry.

Methods

This study was conducted on 175 women who underwent CT between March of 2006 and May of 2008. For making an objective assessment, one specialist in obsterics and gynecology measured the obstetrical conjugate, the true conjugate and the diagonal conjugate on the sagittal plane and the transverse diameter, the intertuberous diameter and the interspinous diameter on the coronal plane. The patients who underwent total hysterectomy or those who had a disease of the uterus were excluded from the current analysis.

Results

A total of 175 Korean women were examined, and their ages ranged from 20 to 50 years. The mean age was 37.6 ± 7.4 years. The interspinous diameter that was measured on CT scans was 94.6 ± 7.8 mm in the vaginal delivery group (n=84) and this was 90.9 ± 6.6 mm in the cesarean section group (n=20). This difference reached statistical significance.

Conclusion

Our study examined the difference in the pelvic architecture with using CT and we found that the interspinous diameter can be the important determinant that affects normal vaginal delivery. Of these pelvimetric parameters, a wider interspinous diameter was significantly associated with vaginal delivery. Multi-displinary approaches are warranted to examine this relation with regard to the various factors that are involved in delivery.

The maternal bony pelvis is an important factor that affects the degree of soft tissue damage that occurs during parturition and for choosing the mode of delivery [1]. It is known that such factors as a spacious inlet, a large interspinous diameter and a wide suprapubic arch are associated with a normal vaginal delivery [1]. Childbirth is a major cause of pelvic prolapse, and so conducting anatomical studies on the materal pelvic structure are essential for examining the structural changes of the pelvic bone that occur during parturition and the possible subsequent prolapse of organs in the pelvic floor. However, there have been no such studies due to a lack of measurement methods in this field. Recent studies [2-4] have found that computed tomography (CT) pelvimetry is easier to perform and more accurate and it causes less distortion than does the conventional x-ray technique. The purposes of the current study are to examine the bony pelvis dimensions in Korean women by using CT pelvimetry and to identify its association with the mode of delivery.

The current study was conducted on 175 patients who underwent pelvic CT between March of 2006 and May of 2008. These patients' medical records were retrospecively reviewed and the following data was evaluated: age, parity, height, weight, and the mode of delivery. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the university and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards for human research established by the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consents were obtained.

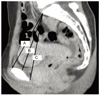

The pelvimetry studies were done with a CT scanner (Siemens Medical Systems Inc., Madison, WI, USA) as described by Federle et al. [2] All the CT measurements were made by one gynecologist. Six pelvic dimensions were measured for each woman. The obstetrically important anteroposterior diameter is the shortest distance between the promontory of the sacrum and the symphysis pubis, and this is designated the obstetrical conjugate. The anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic inlet has been identified as the true conjugate between the promontory of the sacrum and the symphysis pubis. The diagonal conjugate was determined by measuring the distance from the lower margin of the symphysis to the promontory of the sacrum (Fig. 1). The transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet was measured on the anteroposterior radiograph and this was defined as the maximum transverse distance of the pelvic outlet (Fig. 2). The interspinous diameter of the midpelvis was measured on the axial radiograph and this was defined as the distance between the ischial spines (Fig. 2). The intertuberous diameter of the pelvic outlet was measured on the anteroposterior radiograph and this was defined as the distance between the inner aspects of the ischial tuberosities (Fig. 2). The pelvimetries and measurements were performed on the radiographs by using electronic calipers with an internal scale. The paired t-test was used for statistical analysis and P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

A total of 175 Korean women were examined, and their ages ranged from 20 to 50 years. The mean age was 37.6 ± 7.4 years. Of them, 84 patients had vaginal delivery and 20 underwent cesarean operations (The indication of cesarean section was cephalopelvic disproportion). On the CT scans, a total of 175 patients had a true conjugate of 125.0 ± 9.0 mm, an obstetrical conjugate of 119.7 ± 9.5 mm, a diagonal conjugate of 133.5 ± 10.0 mm, an interspinous diameter of 94.0 ± 7.2 mm, an intertuberous diameter of 97.7 ± 10.1 mm and a transverse diameter of 124.8 ± 6.3 mm. The interspinous diameter, which was measured on the CT scans, was 94.6 ± 7.8 mm in the vaginal delivery group and 90.9 ± 6.6 mm in the cesarean section group. This difference reached statistical significance (Table 1).

An obstetrical conjugate is the shortest distance between the promontory and symphysis pubis, and it is obsterically important and it normally exceeds 10 cm. An obstetrical conjugate is smaller than a true conjugate. A diagonal conjugate is clinically used and it is the distance ranging from the inferior margin of the symphysis pubis to the promontory. This can be measured by the internal digitation, from which a value of 1.5-2.0 cm is subtracted and this is estimated as an obsterical conjugate.

In our study, a total of 175 patients had a true conjugate of 125.0 ± 9.0 mm and an obstetrical conjugate of 119.7 ± 9.5 mm. This (175 patients) showed that the obstetrical conjugate was slightly longer than delivery group (104 patients). This difference is assumed to originate from the measurements made in younger women who have not experience delivery. In the cases for which the delivery was done, the measurements were longer in the order of the diagonal conjugate, the true conjugate and the obstetrical conjugate [5].

The midpelvis is a space where the ischial spine is present. The distance between the ischial spines is approximately 10 cm and it is the narrowest part of the pelvis. Directly measuring the midpelvis is clinically impossible. Contracted midpelvis is more common than inlet contraction and it frequently causes transverse arrest of fetal head, which potentially can lead to a difficult midforceps operation or to cesarean delivery [6].

In the cases in which the ischial spine is markedly protruded, the lateral wall gradually becomes narrower and the anterior surface of the sacrum is easily palpated, and stenosis is then suspected. As for the clinical assessment of the size of the pelvic inlet, if the distance between the ischial tuberosities exceeds 8 cm, then this is considered normal [7]. To predict a vaginal delivery, a pelvimetry measuring the bony structure of the pelvis is a method of assessing the materanl pelvis with using radiography or CT. X-ray pelvimetry has been widely over the years and has been generally accepted as one of the clinical tools in evaluating cephalopelvic disproportion but since labor and its outcome are a very delicate and dynamic process [7]. The results of pelvis radiography, which have been reported on in Korea, show that the frequency of a cesarean operation was relatively higher for the cases for which the anterior and posterior width of pelvic inlet were smaller than 10 cm and the transverse length of the midpelvis was smaller than 8.5 cm [8].However, Pattinson [9] suggested that in regard to the pelvimetry, for the women for whom a pelvic radiography was performed, the frequency of cesarean operation was more than two times higher and the perinatal outcome was not particularly improved. For this reason, a pelvic radiography exam has not been recommended.

In our study, of pelvimetric parameters, a wider interspinous diameter was significantly associated with vaginal delivery.

Fetopelvic disproportion arises from diminished pelvic cavity, excessive fetal size, or more usually, a combination of both. Any contraction of the pelvic diameters that diminishes its capacity can create dystocia during labor. There may be contractions of the pelvic inlet, the midpelvis, or the pevic outlet, or a generally contracted pelvis may be used by combinations of these [6].

Conducting a study on the correlation between the pelvic structure and obsterical damage is surely important in the fields of obstetrics and gynecology. Our study has some limitations as it was performed in a retrospective study and the patients were not a typical group, but rather, they were a group of patients who underwent a CT exam of the pelvis. However, our study is of significance in that it is the first to perform a CT exam to measure the pelvimetric parameters of Korean women and we analyzed their correlation with the mode of delivery. This study will be of great help for determining a mode of delivery at the time of the prenatal diagnosis, as well as accomodating patients to the obsteric delivery method. Our results should be confirmed by performing a similar study in the future with a larger patient population.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Nichols DH, Randall CL. Vaginal surgery. 1996. 4th ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

2. Federle MP, Cohen HA, Rosenwein MF, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Cann CE. Pelvimetry by digital radiography: a low-dose examination. Radiology. 1982. 143:733–735.

3. Gimovsky ML, Willard K, Neglio M, Howard T, Zerne S. X-ray pelvimetry in a breech protocol: a comparison of digital radiography and conventional methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985. 153:887–888.

4. Hankins GDV, Clark SL, Cunningham FG, Gilstrap LC III. Operative obstetrics. 1995. Norwalk (CT): Appleton & Lange.

5. Speroff L, Fritz MA. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 2005. 7th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

6. Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JH, Rouse DJ, Spong GY. Williams obstetrics. 2010. 23rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

7. Anderson N, Humphries N, Wells JE. Measurement error in computed tomography pelvimetry. Australas Radiol. 2005. 49:104–107.

8. Park KH, Park EJ, Kim WW. A clinical study of X-ray pelvimetry. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1982. 25:87–95.

9. Pattinson RC. Pelvimetry for fetal cephalic presentations at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000. (2):CD000161.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download