Abstract

Objectives

Infection involving the orbit, zygomatic space, lateral pharyngeal space, or hemifacial and oral floor phlegmon is referred to as cervicofacialvinfection (CFI). When diagnosis and/or adequate treatment are delayed, these infections can be life-threatening. Most cases are the result of odontogenic infections. We highlight our experiences in the management of this life-threatening condition.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients who presented with CFI from December 2005 to June 2012 at the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinic or the Accident and Emergency Unit of Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital (Zaria, Nigeria). The medical records of all patients who presented with either localized or diffuse infection of the maxillofacial soft tissue spaces were retrospectively collected. Data collected was analyzed using SPSS version 13.0 and are expressed as descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results

Of the 77 patients, 49 patients (63.6%) were males, a male to female ratio of 1:7.5. The ages ranged from two years to 75 years with a mean of 35.0±19.3 years, although most patients were older than 40 years. The duration of symptoms prior to presentation ranged from 6 to 60 days, with a mean of 11.0±9.4 days. More than 90% of the patients presented to the clinic within the first 10 days. The most commonly involved anatomical space was the submandibular space (n=29, 37.7%), followed by hemifacial space (n=22, 28.6%) and buccal space (n=7, 9.1%). Ludwig angina accounted for about 7.8% of the cases.

Infection involving the orbit, zygomatic space, lateral pharyngeal space, or multifacial (unilateral) and oral floor phlegmon are known as cervicofacial infections (CFIs). When diagnosis and/or adequate treatment are delayed, such infections can be life-threatening1. Orofacial infections are a public health concern with regard to dental diseases and orofacial trauma, and they are common in poor patients lacking proper health resources. Patients affected by such infections typically present to emergency rooms2. These infections frequently result in cellulitis or abscess formation involving at least one facial space3.

Infection of the anatomic spaces of the head and neck are graded with regard to severity based on the level to which they threaten the airway or vital structures, such as the heart and mediastinum or cranial contents. The severity can either be low, moderate, or high4. A lower severity is noted when the infection does not threaten the airway. Infections of the spaces that can hinder access to the airway due to swelling or trismus are considered to be of moderate severity, while those that obstruct or deviate the airway or threaten vital structures are graded as severe4.

Anatomical and microbial factors as well as impairment in host resistance, compounded by a delay in receiving adequate treatment in the early stages, can result in progression of a localized infection into a CFI5. Predisposing factors such as alcoholism, immunosuppression, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and multiple underlying medical conditions have been reported to increase the risk of odontogenic infection2. The long hospital stay often associated with these infections can become an economic factor for both the patient and society. These CFI generally respond to antimicrobial chemotherapy and/or surgical intervention.

The aim of this paper is to present our experience in the management of CFI and the challenges in a resource-limited environment.

This is a retrospective study of patients who presented with CFI to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinic or the Accident and Emergency Unit of Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital (Zaria, Nigeria), between December 2005 and June 2012. The medical records of all patients who presented with either localized or diffuse infection of the head and neck soft tissue spaces were collected. Patients who presented with dentoalveolar abscesses or osteomyelitis were excluded. Information obtained were demographics, presenting complaint, time of presentation, nature of swelling, source of infection, presence of any underlying comorbidity, complications, degree of mouth opening, as well as use of self-medication and herbal medications. In addition, the temperature at presentation; types of treatment; results of microscopy, culture, and sensitivity (MCS); and length of stay (LOS) in the hospital were noted.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Qualitative variables were expressed as frequency and percentage, while quantitative variables were reported as mean and standard deviation. Inferential statistics were performed using chi-square test or independent sample t-test as appropriate. A P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

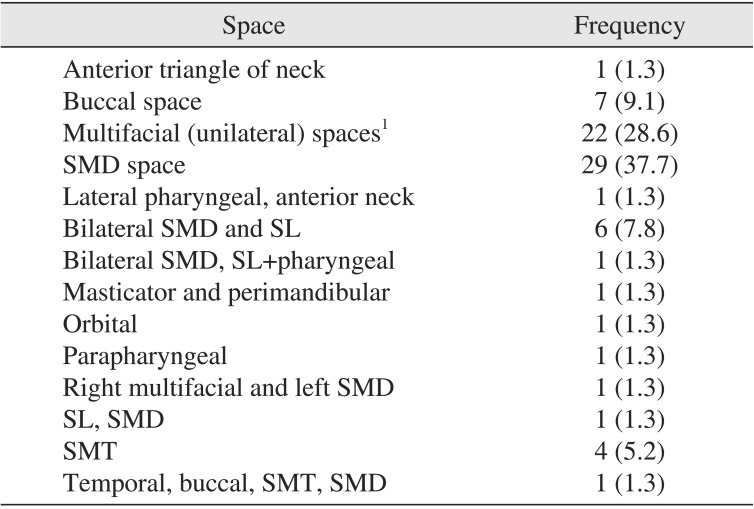

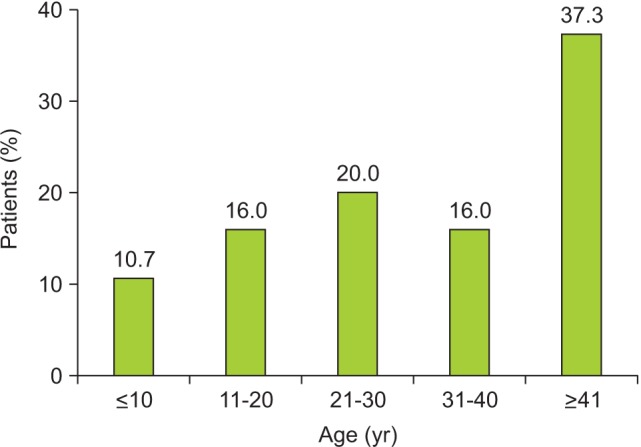

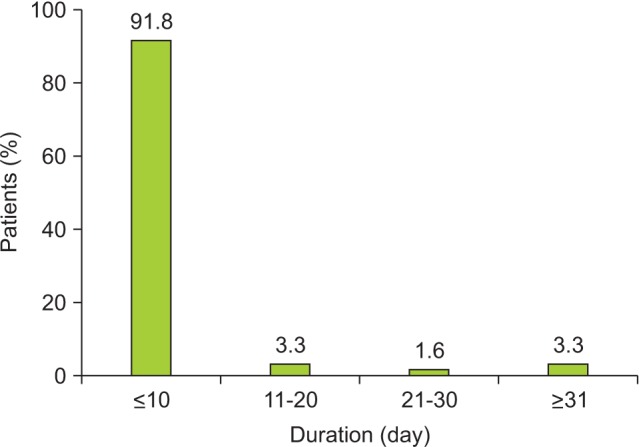

Seventy-seven patients comprised of 49 male (63.6%) and 28 female (36.4%) were analyzed, resulting in a male to female ratio of 1:7.5. The ages ranged from 2 to 75 years, with a mean of 35.0±19.3 years, although most were older than 40 years.(Fig. 1) The duration of symptoms prior to presentation ranged from 6 to 60 days, with a mean of 11.0±9.4 days. More than 90% of the patients presented to the clinic within the first 10 days.(Fig. 2) The majority of patients had only primary school education (88.6%), and this was distantly followed by those with secondary school education (5.7%), while those who attained university and quaranic education were equally distributed at 2.9%. All patients presented with facial swelling, which was either diffuse (Fig. 3) or localized. Other presentations included pain (90.9%), toothache (58.4%), dysphagia (38.9%), and pus discharge (29.8%). About 65.2% of patients presented with trismus, and 64.3% reported having used traditional herbal medications prior to presentation at the hospital. The most commonly involved anatomical space was the submandibular space (n=29, 37.7%), followed by the multifacial space (unilateral) (n=22, 28.6%) and the buccal space (n=7, 9.1%). Ludwig angina accounted for about 7.8% of the cases.(Table 1)

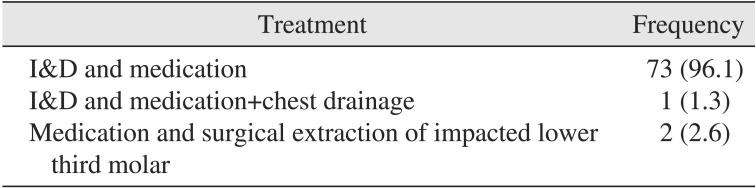

The admitted, non-diabetic patients received an infusion of 0.9% saline (Dana Pharmaceutical, Lagos, Nigeria) and 5% dextrose (Juhel Nigeria Ltd., Enugu, Nigeria). All patients underwent incision and drainage (I&D) under local anesthesia; pus or swab was collected for MCS, and 63.4% were admitted to the hospital and received parenteral medications, typically metronidazole (Juhel Nigeria Ltd.), crystalline penicillin (Shanxi Federal Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Jinzhong, China), gentamicin (Lek Pharmaceutical and Chemical Company, Ljubljana, Slovania), and rocephine (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland); the remaining 36.6% were treated on an out-patient basis with oral drugs such as lincomycin, metronidazole, and analgesic. Following I&D, corrugated rubber drains (Fig. 3) were inserted and secured using sutures. The temperature range at admission was 37.5℃ to 39.9℃.

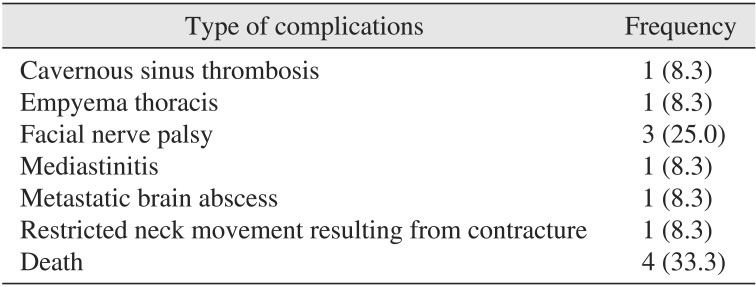

About 15.6% of patients had one complication, and facial nerve palsy was the most common, observed in 25% of the cases. Other complications are shown in Table 2. Of the 12 patients with complications, four patients (33.3%) died, resulting in an overall mortality among all patients of 5.2%. The use of traditional herbal medications had no significant influence on the complications (χ2=1.831, degree of freedom [df]=1, P=0.176).

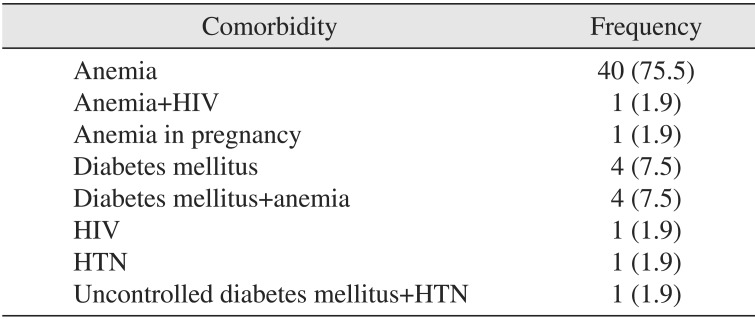

Anemia was the most common comorbidity (n=40, 75.5%), followed by diabetes mellitus either in isolation or occurring concurrently with other comorbidities, and this accounted for about 17% of the cases.(Table 3) There was a strong association between time of presentation and presence of comorbidity (χ2= 65.648, df=14, P<0.001). Thus, patients who presented late were more likely to develop comorbidity compared with early presenters.

The modality of treatment was not stated for one of the patients. Of the remaining 76 patients, about 98.7% received I&D and medication. Other treatments administered are shown in Table 4. About 13% of patients had repeat I&D, and patients with trismus were encouraged to perform mouth exercise using a wooden spatula or chewing sugarless gum. The wounds were dressed twice daily with gauze soaked in diluted hydrogen peroxide and eusol.

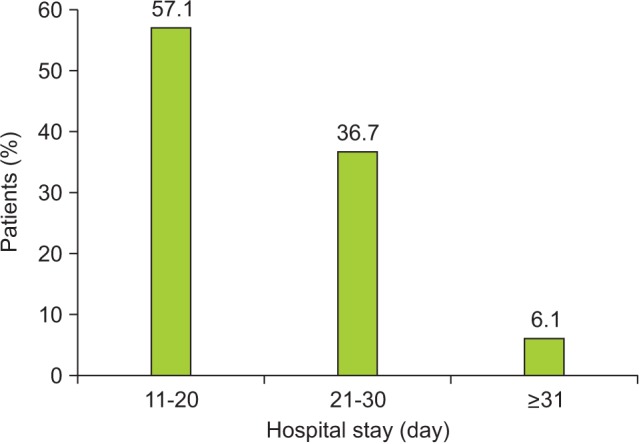

The results of microscopy showed that only about 23.3% of the specimens were culture-positive. One possible reason for this low finding is that patients were taking medication (self-prescribed or prescribed at referring centers). The isolated organisms were Streptococcus pyogenes, Pseudomonas species, and Staphylococcus aureus. The length of stay in the hospital ranged from 4 to 42 days, with a mean of 15.0±7.6 days. About half of the patients (57.1%) spent 11 to 12 days in the hospital.(Fig. 4) The length of hospital stay was significantly associated with type of treatment received (χ2=19.174, df=4, P=0.001).

CFI was found to be more common in men (62.3%) than women, in agreement with the 50.9% to 65% of affected males reported by previous authors236789. Storoe et al.10 reported that, while some studies showed a male predilection between 59% to 66%, others presented a female predilection of 59%. Other studies found no sex predilection in CFIs1011. The low female predilection has been attributed to the better oral health and tendency to seek oral health care noted in women. The patient ages ranged from two years to 75 years, with a mean of 35.0±19.3 years. This is lower than some previous findings36911 but higher than the mean age from other studies712.

The most commonly affected anatomical space was the submandibular space (n=29, 37.7%), followed by the buccal space (n=7, 9.1%) and submasseteric space (n=4, 5.2%). This is in contrast to a previous study reporting that the medial masticator space was the most commonly involved fascial space, followed by the submandibular space13. The frequency of submandibular space involvement recorded in this study is lower than that in other reports3512 but higher than findings from other studies810. Of the previously reported involved spaces, the hemifacial space was the most common, and involvement of multiple spaces has been attributed to delay in presentation.

Although different imaging techniques have been used for diagnosing odontogenic infections, a computed tomography scan is considered the gold standard owing to its superiority in diagnosing deep space infections1114. Ultrasound has been suggested as one possible modality for imaging of infections; however, thus far, it has not been successful in detecting deep fascial space infections11.

Ludwig's angina constituted 7.8% (6 cases) of all CFIs, and this is lower than findings from a similar study in northern Nigeria12. Ludwig's angina is a fatal progressive gangrenous cellulitis and edema of the soft tissues of the neck and floor of the mouth. Airway compromise has been a leading cause of death due to this infection. Two of the four mortalities recorded in this study were observed in patients with Ludwig's angina. Their causes of death were not known as no autopsy was carried out. The probable cause is airway obstruction or endotoxic shock resulting from septicemia. Although tracheostomy has been used to secure the airway in patients with CFI5, none of our patients underwent tracheostomy. However, endotracheal intubation was attempted on one patient to secure the airway after I&D. This was unsuccessful, and the patient eventually died.

Infection of spaces that can hinder access to the airway as a result of swelling or trismus carry a moderate threat to the airway13. Even though 65.3% of the patients in this study had trismus, only about 10% of them showed clinical features of threat to the airway.

The mean duration of presenting complaint was 11.0±9.4 days, which was higher than the result from a previous study in Nigeria12. Although most patients reported recurring symptoms such as pain prior to the onset of CFI, they only presented when there as associated swelling5.

Fascial space infections of the head and neck region are mainly caused by bacterial infection arising from preexisting dental caries-related sequelae such as pulpitis and apical periodontitis, pericoronitis, or periodontal disease1215. Other documented causes include tonsillitis, gunshot injury, peritonsillar or parapharyngeal abscess, mandibular fracture, oral laceration/piercing, or submandibular sialadenitis12. We found that 58.4% of the patients had odontogenic infection, although the etiologies in children were unknown. It has been suggested that ductal openings of salivary glands are a probable portal of entry in infants1216.

Management of CFI involves a combination of antibiotic, surgical decompression of the localized or diffuse cellulitis, rehydration, and removal of the source of infection. In the present study, the offending tooth/teeth were extracted. In addition, crystalline penicillin was administered empirically together with metronidazole and gentamycin and then altered based on the results of MCS. Crystalline penicillin is not abused in our environment; hence it was used as a first-line drug17. The effectiveness of penicillin in the treatment of CFI has been documented in a similar study8. Our patients were converted to oral drugs once they were able to swallow.

Although traditional herbal medications were used by most of the patients, this did not significantly affect the morbidity rate. This is surprising and contrary to a previous Nigerian study12 and can be explained by the early presentation to the hospital by a majority of our patients. More than 90% of the patients in the present study presented within the first 10 days of symptom onset, and this was higher than the 58.9% previously reported12.

According to our study, life-threatening CFI, including Ludwig's angina, can be managed under local anesthesia. This is in agreement with a previous report in Nigeria12 but disagrees with earlier published reports in which the majority of Ludwig's angina cases were treated under general anesthesia511. The management of CFI under local anesthesia has the advantages of safety, economy, and less technique-sensitive compared to treatment under general anesthesia, especially in developing countries where resources might be limited and competent anesthetists are few or not available. In addition, local anesthesia avoids the complications of general anesthesia. The presence of comorbidity in some of our patients also contraindicated any planned use of general anesthesia in the present series.

Orofacial odontogenic infections are known to be poly-microbial, and the bacteriology, though complex, often reflects the commensal oral flora15181920, consisting of both anaerobes and aerobes. More than 65% of the isolated species are obligate anaerobes, and these are isolated from virtually all odontogenic infections, although aerobes are also isolated from about one-third of infections15. The inability to carry out anaerobic culture in our center has a negative influence on our results, and this challenge has been previously highlighted12. S. pyogenese and S. aureus have been previously isolated in our environment1721 and were found in microbial cultures in the present study. In odontogenic infection, a whole variety of microorganisms can be identified, many of which are not culturable using standard methods22. The ability to determine rapid identification of all the infecting organisms will definitely improve the treatment of odontogenic infections. Mathew et al.5 had no growth on 83.6% of specimens sent to the laboratory which was a little higher Of the microbiological specimens analyzed in this study, 76.7% yielded no growth. This is similar to findings from another study5. Other studies did not consider routine microbiological culture necessary but only indicated such a need when the patient failed to respond effectively to antibiotic therapy6.

The mean LOS in our study was 15.0±7.6 days, and this is higher than the 3.1 to 5.2 days observed in other studies3461112. The LOS has been reported to be positively correlated with age, presence of co-morbidity, temperature on admission, number of involved anatomical spaces, use of intensive care unit (ICU), and involvement of deep spaces351123. None of our patients required ICU admission. Moreover, ICUs in developing countries tend to be poorly equipped and possess virtually no functioning instruments. The majority of the patients were of low socioeconomic status, a population in which the length of hospital stay is usually high. The high LOS noted in the present study could be attributed to the presence of comorbidity and involvement of multiple fascial spaces in the patients reviewed. The role of comorbidity in the etiology and prognosis of CFI is well documented1217. Anemia (nutritional) was the single most common comorbidity recorded in this study, followed by diabetes mellitus. All our patients with nutritional anemia were placed on a special diet by the hospital nutrition unit. Other authors have reported diabetes mellitus as the most common comorbidity511. The prevalence of complications in this study was 15.6%, with an overall mortality of 5.2%.

CFI is a potentially lethal condition that necessitates aggressive medical and surgical management. The major challenge in management of CFI in our environment is lack of disease awareness, which can result in late presentation of patients and the attendant morbidity and mortality. In addition, lack of appropriate resuscitative facilities, especially in a resource-limited environment like ours, can further contribute to poor treatment outcome.

References

1. Adekeye EO, Adekeye JO. The pathogenesis and microbiology of idiopathic cervicofacial abscesses. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982; 40:100–106. PMID: 6950044.

2. Wang J, Ahani A, Pogrel MA. A five-year retrospective study of odontogenic maxillofacial infections in a large urban public hospital. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005; 34:646–649. PMID: 15955663.

3. Bouloux GF, Wallace J, Xue W. Irrigating drains for severe odontogenic infections do not improve outcome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013; 71:42–46. PMID: 22726703.

4. Flynn Thomas R. Principles of management of odontogenic infections. In : Miloro M, Ghali GE, Larsen P, Waite P, editors. Peterson's principle of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2nd ed. London, Hamilton: BC Decker Inc.;2004. p. 277–293.

5. Mathew GC, Ranganathan LK, Gandhi S, Jacob ME, Singh I, Solanki M, et al. Odontogenic maxillofacial space infections at a tertiary care center in North India: a five-year retrospective study. Int J Infect Dis. 2012; 16:e296–e302. PMID: 22365137.

6. Boffano P, Roccia F, Pittoni D, Di Dio D, Forni P, Gallesio C. Management of 112 hospitalized patients with spreading odontogenic infections: correlation with DMFT and oral health impact profile 14 indexes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012; 113:207–213. PMID: 22677738.

7. Cunningham LL Jr, Madsen MJ, Van Sickels JE. Using prealbumin as an inflammatory marker for patients with deep space infections of odontogenic origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:375–378. PMID: 16487796.

8. Poeschl PW, Spusta L, Russmueller G, Seemann R, Hirschl A, Poeschl E, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility and resistance of the odontogenic microbiological spectrum and its clinical impact on severe deep space head and neck infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010; 110:151–156. PMID: 20346713.

9. Farmahan S, Tuopar D, Ameerally PJ. The clinical relevance of microbiology specimens in head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014; 52:629–631. PMID: 24906248.

10. Storoe W, Haug RH, Lillich TT. The changing face of odontogenic infections. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001; 59:739–748. PMID: 11429732.

11. Jundt JS, Gutta R. Characteristics and cost impact of severe odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012; 114:558–566. PMID: 22819453.

12. Osunde OD, Akhiwu BI, Efunkoya AA, Adebola AR, Iyogun CA, Arotiba JT. Management of fascial space infections in a Nigerian teaching hospital: a 4-year review. Niger Med J. 2012; 53:12–15. PMID: 23271838.

13. Flynn TR, Shanti RM, Hayes C. Severe odontogenic infections, part 2: prospective outcomes study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:1104–1113. PMID: 16781344.

14. Ariji Y, Gotoh M, Kimura Y, Naitoh M, Kurita K, Natsume N, et al. Odontogenic infection pathway to the submandibular space: imaging assessment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002; 31:165–169. PMID: 12102414.

15. Gill Y, Scully C. Orofacial odontogenic infections: review of microbiology and current treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990; 70:155–158. PMID: 2290641.

16. Adekeye EO, Brown AE, Adekeye JO. Cervicofacial abcesses of unknown origin: a survey of eighty-one cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978; 45:831–840. PMID: 355964.

17. Fomete B, Ononiwu CN, Agbara R, Idehen OK, Okeke UA. Cervicofacial necrotizing fasciitis: case series and review of literature. Case Study Case Rep. 2013; 3:26–33.

18. Gilmore WC, Jacobus NV, Gorbach SL, Doku HC, Tally FP. A prospective double-blind evaluation of penicillin versus clindamycin in the treatment of odontogenic infections. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988; 46:1065–1070. PMID: 3142979.

19. Warnke PH, Becker ST, Springer IN, Haerle F, Ullmann U, Russo PA, et al. Penicillin compared with other advanced broad spectrum antibiotics regarding antibacterial activity against oral pathogens isolated from odontogenic abscesses. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2008; 36:462–467. PMID: 18760616.

20. Al-Qamachi LH, Aga H, McMahon J, Leanord A, Hammersley N. Microbiology of odontogenic infections in deep neck spaces: a retrospective study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 48:37–39. PMID: 19178989.

21. Fomete B, Saheeb BD, Obiadazie AC. A prospective clinical evaluation of the effects of chlorhexidine, warm saline mouth washes and microbial growth on intraoral sutures. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015; 14:448–453. PMID: 26028872.

22. Flynn TR, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Susarla SM, Shanti RM. Molecular methods for diagnosis of odontogenic infections. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 70:1854–1859. PMID: 22326175.

23. Christensen B, Han M, Dillon JK. The cause of cost in the management of odontogenic infections 2: multivariate outcome analyses. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013; 71:2068–2076. PMID: 23945517.

Table 1

Anatomical spaces involved in the patients (n=77)

Table 2

Types of complications recorded in the patients (n=12)

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download