INTRODUCTION

Treatment options for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the most common type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma [

1], differ for patients with limited disease compared to those with advanced disease [

2]. Therefore, a clear definition of "limited disease" is required. In previously published studies, limited disease has also been referred to as "localized disease" [

3,

4], and the terms "early-stage" or "low-stage" have been used. This category of disease is defined as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) of Ann Arbor stage I and non-bulky stage II. Bulky disease is defined as any mass with a maximum diameter greater than 10 cm or any mediastinal mass exceeding 1/3 of the maximum transthoracic diameter [

2]. Because patients with bulky stage II lymphoma have a prognosis similar to those with stage III or IV disease, they usually are regarded as having advanced disease [

2].

The stage-modified International Prognostic Index (IPI) has proven useful for studies of limited disease in patients with NHL [

3,

5]. Adverse risk factors of stage-modified IPI include the following 4 clinical parameters: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status 2 to 4, non-bulky stage II, age >60 years, and elevated level of serum lactose dehydrogenase. Patients with no adverse risk factors have been reported to have an excellent prognosis when treated with 3 cycles of doxorubicin-containing combination chemotherapy plus involved-field radiation therapy (IFRT) [

6]. In a study reported by the British Columbia Cancer Agency, the 5-year and 10-year overall survival (OS) rates were 97% and 90%, respectively [

5]. Excellent prognosis was achieved regardless of the treatment strategy, including a brief course of combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP) plus IFRT, in addition to 8 cycles of CHOP [

3], or an aggressive combination regimen containing doxorubicin [

7].

For patients with limited disease NHL and any adverse risk factor, both chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy alone have been used. These treatment options were based on the results of numerous previous studies [

8-

11]. In the early 1980s, chemotherapy followed by subsequent radiotherapy was found to be superior to radiotherapy alone, which was the standard treatment at that time [

11]. During the same period, chemotherapy alone was also accepted as an effective treatment option for limited disease NHL [

8], and a brief course of chemotherapy followed by IFRT was further tested and confirmed to be effective [

9,

10].

The emergence of rituximab, a monoclonal antibody to CD20, for clinical treatment has substantially improved the EFS and OS in both elderly [

12] and young [

13] patients with DLBCL. Addition of rituximab to 3 cycles of CHOP chemotherapy with subsequent IFRT has been evaluated and was shown to be effective in a phase II study [

14]. Although the current National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines for NHL recommends both 3 cycles of rituximab with CHOP (R-CHOP) plus IFRT, and 6-8 cycles of R-CHOP with or without subsequent IFRT [

15], the recommendations are based on data and practices of the pre-rituximab era. No study has re-evaluated the 2 treatment options in patients with limited disease DLBCL. In this study, the efficacy and tolerability of the 2 treatment options in limited disease DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP were compared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were collected and reviewed from DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP at a single institution, Gachon University Gil Hospital (GUGH), between June 2004 and September 2009. Patients with Ann Arbor stage I or non-bulky stage II were selected for this study, and were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were included in the study if they had histological confirmation of DLBCL according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria without any previous treatment for the lymphoma. Patients with DLBCL originating from transformation of an indolent lymphoma, with primary involvement of the central nervous system or with human immunodeficiency virus-associated lymphoma were excluded from the analysis. The institutional review board at GUGH granted permission for this retrospective study.

A cycle of R-CHOP consisted of 375 mg/m2 of rituximab, on day 1 of each cycle and a combination of 750 mg/m2 of cyclophosphamide, 50 mg/m2 of doxorubicin and 1.4 mg/m2 of vincristine (maximal dose of 2 mg), all on day 1. Patients also received 100 mg/day of prednisolone PO for 5 days. The immunochemotherapy cycle was repeated every 21 days. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor support was limited to secondary neutropenia prophylaxis.

IFRT consisted of 30-36 Gy for patients achieving a complete response (CR), with a boost volume to a maximum of 50-55 Gy for patients failing to achieve a CR, in daily fractions of 1.8 Gy (5 days a week) in predetermined standard ports involving only the lymph node region(s) or organs affected by overt disease and calculated at the midplane of the target volume or at 3-cm depth for the supraclavicular regions. Most IFRT treatments were completed in 4-5 weeks. The duration of treatment depended on the dose delivered.

Response evaluation for patients with DLBCL was performed 3 months after treatment completion by spiral computed tomography (CT) of the lymphoma-involved area. Positron emission tomography-CT could also be used to confirm the final response status. Responses were evaluated according to the International Workshop criteria [

16]. Follow-up physical examinations and laboratory screenings were performed every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for 3 years, and annually thereafter.

EFS was defined as survival free of progression, relapse, or death from lymphoma or treatment-related toxicity. OS was defined as survival free of death from any cause. Survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log rank test. Probability values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Fisher's exact test was used to compare baseline characteristics between patients treated with subsequent IRFT and those treated with additional R-CHOP. SPSS software version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

1. Patients

Among 87 patients treated with R-CHOP therapy, 43 patients had Ann Arbor stage I or II DLBCL (49.4%). Because 4 of the 43 patients had a bulky mass at initial presentation, 39 patients (44.8%) were classified as limited disease DLBCL. The 4 patients with bulky stage II disease received 6-8 cycles of R-CHOP with (1 patient) or without (3 patients) IFRT.

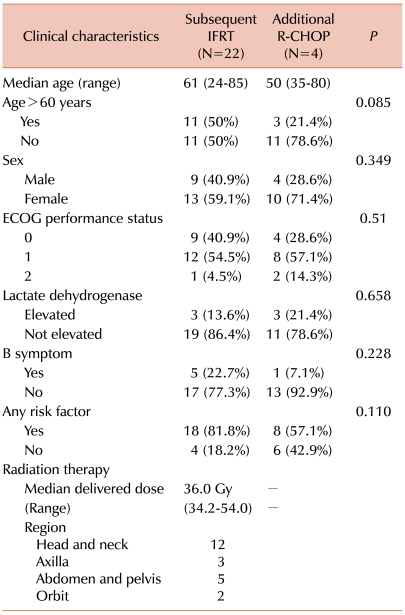

The median age of the patients with limited disease was 52 years (range, 24-85). Thirty-six of the 39 patients with stage I or non-bulky stage II disease underwent either 3-4 cycles of R-CHOP followed by IFRT (N=22) or 6-8 cycles of R-CHOP alone (N=14). Three patients belonged to neither treatment group. A male patient with stage I disease and without any adverse factors initially presented with isolated left inguinal lymph node enlargement. He was diagnosed with DLBCL on the basis of an excision biopsy of the lymph node, and after 4 cycles of R-CHOP, he had no lesion that required IRFT because of complete excision. A second 73 year-old male patient with no adverse risk factors, except for age, died of treatment-related mortality (TRM) after the third cycle of R-CHOP. A third patient with non-bulky stage II DLBCL refused further treatment after the third cycle of R-CHOP immunochemotherapy.

There was 1 TRM in the 6-8 R-CHOP cycle group. A 74-year-old female patient who had all 4 adverse risk factors died of severe pneumonia after the sixth cycle of R-CHOP. The baseline characteristics of both groups were similar (

Table 1).

2. Treatment outcomes

During the median follow-up period of 34.6 months (range, 9.1-65.4) for patients with limited disease DLBCL, 8 patients (20.5%) experienced an event and 5 of them (12.8%) eventually died. Among these 8 patients, the reported events were relapse or progression of the lymphoma (5 patients), TRM (2 patients), 1 death that was not related to treatment or lymphoma, and sudden cardiac arrest due to acute myocardial infarction (1 patient).

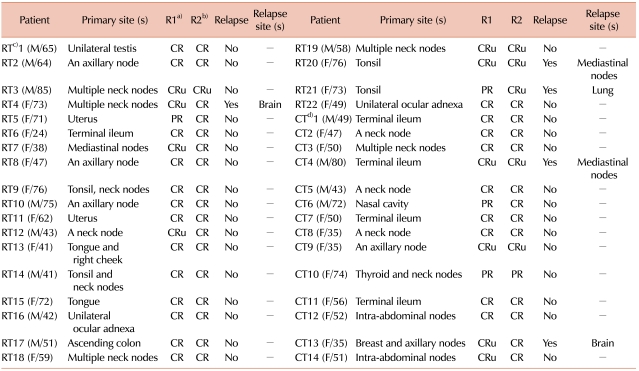

Table 2 shows the disease presentation and treatment outcomes of 36 patients who underwent either subsequent IFRT or additional R-CHOP. Most patients achieved complete response (CR) or CR unconfirmed (CRu) irrespective of the treatment option. Only 2 patients in each group showed partial response (PR) in the interim analysis performed after the initial 3-4 cycles of R-CHOP and only 1 patient, with thyroid lymphoma, had a PR after additional R-CHOP.

Three patients treated with IFRT and 2 patients treated with additional R-CHOP relapsed. All 3 patients treated with IFRT had relapsed because the lesion was outside the previous radiation field.

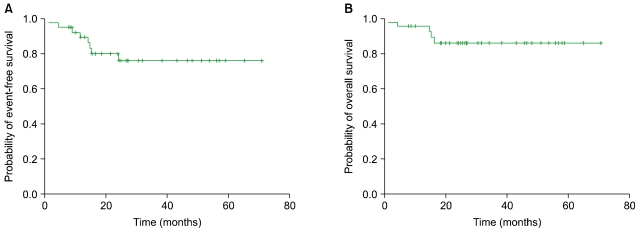

The 3-year EFS and OS were 76.0% and 86.0%, respectively. The median EFS and OS have not yet been reached (

Fig. 1).

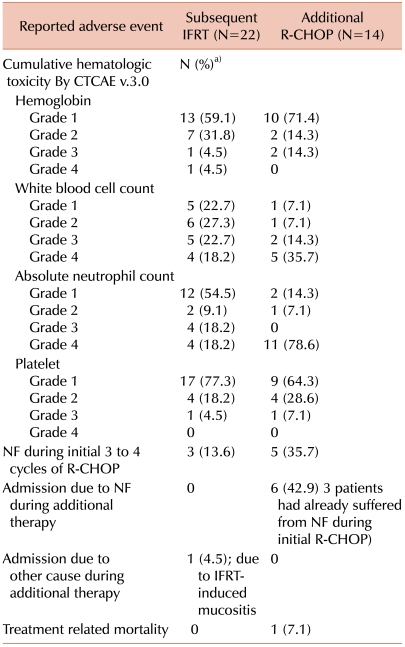

3. Comparison of treatment-related toxicities

Patients who underwent 6-8 cycles of R-CHOP alone showed more frequent grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, probably due to the additional cycles of R-CHOP therapy. Among the 36 patients who underwent either treatment option, 8 patients (22.2%) reported neutropenic fever and required admission for intravenous (IV) antibiotic administration (3 of the 22 patients treated with IFRT and 5 of the 14 patients treated with further R-CHOP) during their first 3-4 cycles of R-CHOP. After completion of the initial R-CHOP, 6 of the 14 patients treated with additional immunochemotherapy reported neutropenic fever that required hospital admission and IV antibiotics. Four of the 6 patients experienced recurrent neutropenic fever after their first 3-4 cycles of R-CHOP, even though they all had a 25% dose reduction of cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin after the previous occurrence of neutropenic fever. In contrast, among the patients treated with subsequent IFRT, no patient had recurrent neutropenic fever. However, 1 of the 22 patients treated with subsequent IFRT required admission for grade 3 mucositis after radiation (

Table 3). There was no TRM in the IFRT group, and there was 1 TRM in the continued immunochemotherapy group.

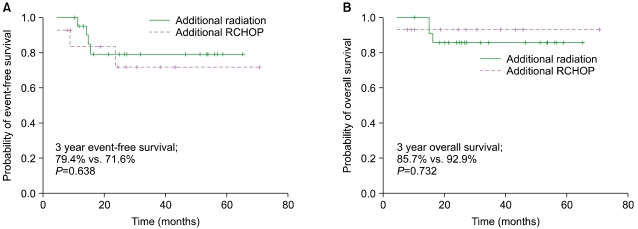

4. Comparison of survival according to treatment option

The 3-year EFS among patients who underwent 3-4 cycles of R-CHOP followed by IFRT and the long course of R-CHOP alone was 79.4% and 71.6%, respectively. Therefore, there was no difference in EFS. In addition, the 3-year OS of patients treated with R-CHOP followed by IFRT and the long course of R-CHOP alone was 85.7% and 92.9% respectively, and the difference was not significant by log-rank test (

Fig. 2).

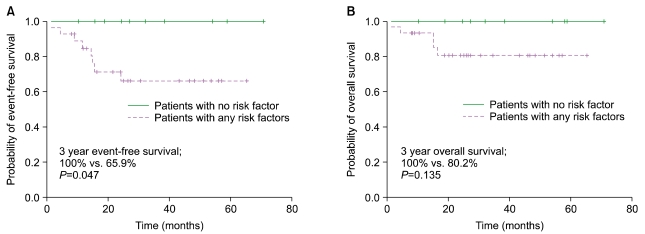

5. Comparison of survival according to adverse risk factors

Among limited disease DLBCL patients, 11 had no adverse risk factors. They did not experience any events, and they were all alive at the time of analysis. In contrast, patients with any of the adverse risk factor had a 3-year EFS of 65.9% (

P=0.047) and a 3-year OS of 80.2% (

P=0.135) (

Fig. 3). Further detailed comparisons of survival according to stage-modified IPI score (e.g., 0 vs. 1, 2 vs. 3, 4 or 0-2 vs. 3, 4, etc.) were not possible because of the limited number of events and deaths.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study showed no significant difference in survival between the 2 commonly used treatment options for DLBCL. Because the prognosis of patients with limited disease DLBCL is generally good, neither treatment group has yet reached the median EFS or OS in our study. Although the patients in both groups showed tolerable toxicities, compared to the patients who underwent IFRT, the patients treated with 6-8 cycles of R-CHOP had more frequent episodes of grade 4 neutropenia and neutropenic fever, which resulted in more hospital admissions for antibiotic treatment. However, there was no significant difference in TRM.

Previous randomized trials that compared a brief course of CHOP followed by IFRT to CHOP alone have reported conflicting data. Miller et al. reported that 3 cycles of CHOP followed by IFRT was superior to 8 cycles of CHOP alone [

3]. In their study, which included 401 patients, the 5-year progression-free survival among patients undergoing CHOP plus IFRT (N=200) and patients undergoing CHOP alone (N=201) was 77% and 64%, respectively (

P=0.03), and the 5-year estimates of OS were 82% and 72%, respectively (

P=0.02). In contrast, Fillet et al. compared 4 cycles of CHOP (N=277) to 4 cycles of CHOP plus IFRT (N=299) in patients aged more than 60 years with no other adverse risk factors according to the age-adjusted IPI [

17]. In their study, patients with bulky stage II disease were included. There was no difference in EFS or OS at 5 years. With a median follow-up time of 7 years, the reported 5-year EFS was 61% for CHOP alone versus 64% for CHOP plus IFRT, and the 5-year OS was 72% for CHOP alone and 68% for CHOP plus IFRT. IFRT appeared to increase treatment-related toxicity. The 5-year loco-regional failure was 47% without IFRT versus 21% with IFRT. On the basis of these results, both 3-4 cycles of CHOP followed by IFRT and extended cycles of CHOP alone have been used for the treatment of patients with limited disease NHL.

Unlike the previously mentioned randomized studies [

3,

17], we retrospectively analyzed data from limited disease DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP. Therefore, there is the possibility of uneven distribution of patient characteristics. First, if a patient's lesions were not easily accessible for radiation field simulation or if severe post-radiation complications were expected, the physician might prefer prolonged R-CHOP to subsequent IFRT. However, if a patient had a high risk of infection, particularly if the patient had already experienced severe neutropenia due to R-CHOP during the first 3-4 cycles, the physician might decide to perform IFRT instead of additional R-CHOP. As shown in

Table 2, 12 of the 22 patients (54.5%) treated with IFRT had DLBCL lesions in their neck nodes, tonsils, or axillary nodes. Ocular adnexa (2 patients) are also locations that are easily radiated. On the other hand, 6 of the 14 patients (42.9%) treated with additional R-CHOP had intestinal lymphomas or intra-abdominal lymph node lesions. Despite the location of lesions, 2 patients with intestinal DLBCL underwent subsequent IFRT and 6 patients with tonsilar or cervical and/or axillary lymph node DLBCL underwent prolonged R-CHOP instead of IFRT, and they showed good outcomes. Known poor prognosis might be a factor for considering the use of prolonged R-CHOP for treating patients with breast lymphoma and multiple regional lymphadenopathies [

18].

Recurrences are predominantly distant rather than loco-regional in patients with DLBCL [

19]. Therefore, an attempt was made to reduce the rate of relapse in patients with NHL by using an aggressive regimen instead of IFRT. Reyes et al. of the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes del'Adulte (GELA) reported the results of a prospective randomized trial that compared 3 cycles of CHOP followed by IFRT to an aggressive chemotherapy regimen, a combination of doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, bleomycin, and prednisone induction (ACVBP) at 2-week intervals, followed by high-dose methotrexate, etoposide, and cytarabine consolidation [

7]. The patients enrolled in the trial were previously untreated and less than 61 years of age with localized stage I or II aggressive NHL (N=647). The investigators concluded that chemotherapy with 3 cycles of ACVBP followed by sequential consolidation was superior to 3 cycles of CHOP plus radiotherapy. A persistent superior EFS (

P=0.002) and OS (

P=0.01) was found in 574 patients with non-bulky disease in the study, and regardless of tumor stage and the presence or absence of bulky disease, the results were maintained in multivariate analysis. The ACVBP studies were performed only with patients who had no adverse risk factors. Therefore, it is difficult to apply this result to patients with risk of infection or poor performance status. Furthermore, more toxic events were reported in patients who underwent aggressive chemotherapy: 34 episodes of grade 3 infection (11%) and 2 episodes of grade 4 infection (1%) occurred in the chemotherapy group, compared to 4 episodes of grade 3 infection in the chemoradiotherapy group (1%). These results suggest that eradicating microscopic tumors in limited disease lymphomas might not be achieved with 3 cycles of CHOP alone and that the role of IFRT is limited to reducing the local relapse rate. However, for prolonged chemotherapy, the risk of toxicity should be considered according to the individual patient's situation.

Therefore, whether a short course of systemic therapy is effective for reducing the relapse rate remains unconfirmed. One study reported that late (≥4 years of disease-free survival) recurrence in patients with DLBCL was characterized by the same clonal abnormalities observed in the primary disease [

20]; this finding suggests that chemotherapy failed to eradicate occult disseminated disease. This study, with a long follow up, showed a high late-relapse rate, particularly in patients managed with short courses of chemotherapy. Considering the median follow-up duration of 4.4 years in the study conducted by Miller et al. [

3], such late recurrences cannot be ruled out. In our study, all 3 patients with relapse in the IFRT group showed relapsed tumor outside the radiation port. This might support the need for a long duration of systemic therapy to eradicate microscopic disease; however, the number of relapsed patients was too small to analyze.

In our study, although patients treated with 6-8 cycles of R-CHOP tended to be younger and have fewer adverse factors, 6 of the 14 patients eventually required hospital admission. This result suggests that the risk of neutropenic fever should be considered during additional immunochemotherapy. Because this study was a retrospective analysis with a limited sample size and a relatively short follow-up period, a better treatment option for limited disease DLBCL patients who are treated with rituximab-based immunochemotherapy could not be eventually determined.

In conclusion, both subsequent IFRT and additional 3-4 cycles of R-CHOP after 3-4 cycles of R-CHOP immunochemotherapy showed excellent survival among patients with limited disease DLBCL, if they had no risk factors. Toxicities, particularly the risk of neutropenic fever, should be considered when treating DLBCL patients with rituximab-containing treatment. A prospective study with a larger number of patients should be conducted to determine the optimal treatment strategy for DLBCL patients in the rituximab era.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download