Abstract

Background and Objectives

Basal septal thinning or localized aneurysmal dilatation without coronary artery disease has been described as a characteristic finding suggestive of cardiac sarcoidosis. We sought to assess the prevalence of this characteristic echocardiographic finding in patients with pacemaker (PM) or implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD).

Subjects and Methods

Echocardiography of patients who received PM or ICD were retrospectively analyzed. Patients with marked thinning and akinesia confined to the basal septum (type 1), or posterolateral wall resulting in localized aneurysmal outward bulging (type 2) without history of myocardial infarction or significant coronary stenosis were included for analysis.

Results

Among 1,357 consecutive patients, 21 exhibited suggestive echocardiographic findings (type 1/2=15/6) with a mean ejection fraction of 37±11%. The prevalence was 1.2% in the PM group and 4.0% in the ICD group. Only 3 patients showed histologically confirmable sarcoidosis in lymph nodes, lung and heart, respectively. Endomyocardial biopsy was attempted in 6 patients, but failed to demonstrate sarcoidosis. The 1-, 2-, 4- and 6-year clinical events (death, cardiac transplantation and hospital admission)-free survival rates were 100%, 85.7±7.6%, 75.0±9.7% and 48.6±12.4%, respectively. During follow-up, two patients with PM underwent ICD implantation, and another underwent heart transplantation.

Conclusion

Prevalence of echocardiographic features suggesting prevalence of cardiac sarcoidosis is low in patients who underwent device implantation. However, considering the very low yield of endomyocardial biopsy and the rare extracardiac manifestations in cardiac sarcoidosis, characteristic echocardiographic findings could be an adjunctive diagnostic criterion in these patients.

Sarcoidosis is a multi-systemic disease characterized by the formation of cryptogenic granulomas in a variety of tissues.1) The prevalence of cardiac involvement was reported in USA is approximately 20-27% of sarcoid patients, but has been reported to be as high as 58% in Japan.2) The clinical manifestation of cardiac involvement is non-specific, and can include various degrees of atrioventricular block, ventricular arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, or even sudden cardiac arrest as an initial manifestation.

Diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis remains challenging, as previous studies reported that the sensitivity of endomyocardial biopsy, the gold standard for definitive diagnosis, is only 20-30%.2)3) Although patchy pathologic involvement is frequent and does not necessarily accompany any prominent morphological changes, several characteristic morphological changes have been observed in advanced cases with cardiac sarcoidosis. The most common characteristic change is localized wall thinning involving the basal interventricular septum, which was seen in more than 90% of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis.4-6) Ventricular aneurysm, especially in the infero-posterior wall, has been reported to be another characteristic finding of cardiac sarcoidosis.7) Thus, a combination of clinical fe-atures and morphologic changes can form the basis for screening high risk patients. The screening of suspected cases of cardiac sarcoidosis is necessary in order to characterize patients with relatively high risk of cardiac abnormalities such as conduction disturbances, ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden arrest, particularly when these condition cannot be explained by other causes.4) The principal aims of the present study were to evaluate the prevalence of echocardiographic findings suggestive of cardiac sarcoidosis in patients with conduction abnormalities or ventricular arrhythmias, and to describe the clinical characteristics of these patients.

We focus on screening patients with conduction abnormalities or ventricular arrhythmia, and targeted patients who had received device therapy for arrhythmia, including permanent pacemaker (PM) or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). We screened the echocardiographic images of a total of 1,184 patients who had received PMs between January 1989 and December 2007, and 173 patients who had received an ICD between January 1996 and December 2007 at the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, the Republic of Korea. Patients who showed typical morphologic changes suggestive of cardiac sarcoidosis on echocardiography, and who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria according to the guidelines published by the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare8) were included for analysis. Exclusion criteria were established to exclude the possibility of ischemic heart disease, as follow: 1) past medical history of documented myocardial infarction; 2) definite electrocardiography or laboratory abnormalities with chest pain episode; 3) significant stenosis on coronary angiogram. However, as nonspecific perfusion defects can be noted on myocardial perfusion scan in cases of cardiac sarcoidosis,9)10) patients who showed abnormalities on thallium-201 scintigraphy alone were not excluded. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of our institution, and informed consent was obtained from each patient at study entry.

Two types of morphologic changes on echocardiography were considered characteristic morphologic changes suggestive of cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis (Fig. 1). Type 1 was characterized by thinning and akinesia of the basal septum at either parasternal long-axis or apical views (Fig. 1A and B). Aneurysmal dilatation involving the inferior or posterolateral wall was classified as type 2 (Fig. 1C and D). Clinical events were defined as any adverse clinical events, including death, cardiac transplantation, and hospital admission due to cardiac causes during the follow-up period following device implantation. For statistical analysis, we used non parametric methods for categorical and continuous variables. Event rates (±SE) were calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method, with all clinical events by time to first event, and compared those with log-rank test. All p was two sided, and p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significance. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

In 1,184 patients who had received a PM, 214 patients (18.1%) exhibited regional wall motion abnormalities on echocardiography. Among them, 14 patients showed echocardiographic findings suggestive of cardiac sarcoidosis, and thus the prevalence was 1.2% (14/1,184). Among 173 patients who received ICD, 71 (41.0%) patients exhibited regional wall motion abnormalities, of whom 7 had echocardiographic findings suggestive of cardiac sarcoidosis. The estimated prevalence was 4.0% (7/173).

Representative images of two cases of cardiac sarcoidosis (case 10 and 14 in Table 1) were illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3. The first case (case 10) (Fig. 2) is a 53-year old male patient who underwent PM implantation in 2003 due to complete atrio-ventricular block. Since early 2007, progressive dysphasia developed and chest computed tomography revealed multiple lymphadenopathy in the mediastinum. He was referred to our hospital with a suspected diagnosis of lymphoma. Biopsy of a supraclavicular lymph node revealed non-caseating granuloma with negative Ziehl-Neelsen and d-PAS staining consistent with sarcoidosis. Echocardiography showed typical thinning of the basal septum, with ejection fraction of 42%. Systemic sarcoidosis with cardiac involvement was the final diagnosis and prednisolone 60 mg a day was prescribed, which was tapered to 5 mg during follow-up.

The second case (case 14) (Fig. 3) was a 44-year old male who underwent PM implantation due to complete atrio-ventricular block in 2005. Progressive dyspnea developed since early in 2006 and radiofrequency ablation was performed for atrial flutter in December 2006. The patient's condition deteriorated rapidly despite receiving maximum medical therapy for congestive heart failure. Follow-up echocardiography showed progressive thinning of the basal septum. Systemic work-up failed to demonstrate any non-cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis. Endomyocardial biopsy was attempted in September 2007 but failed to demonstrate any evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis. Prednisolone 60 mg a day was administered, which was not effective to control his symptoms. He underwent successful cardiac transplantation in April 2008, and histology showed typical non-caseating granuloma suggesting cardiac sarcoidosis.

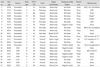

Clinical data of 21 patients whose echocardiographic findings suggested cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis are summarized in Table 1. Patients were aged between 34 to 73 years, with a mean age of 53.8±10.3 years when the device was implanted. Among 14 patients who received PMs, 11 patients presented with complete atrioventricular block, and the remaining patients with trifascicular block (case 5), sinus bradycardia (case 6) and junctional bradycardia (case 9). All 7 patients who received ICD presented with ventricular tachycardia.

Clinical manifestation before device implantation was variable. Nine patients presented with dyspnea. Among them, the most indolent case aggravated gradually over 14 years (case 19). In contrast, in another case without previous abnormality, dyspnea aggravated rapidly just over 2 weeks (case 6). The time interval between the initial symptom and device implantation was relatively short in patients who developed syncope as presenting symptom, and 2 patients received device implantation after 1 week (case 16) and 1 month (case 18) after the initial episode, respectively. On the other hand, in 4 patients with dizziness (case 8, 10, 13, 14), the time interval between initial symptom and device implantation was as long as 1 year in all 4 cases.

Although all 7 patients who underwent ICD implantation were uniformly diagnosed with VT, the initial manifestation was also variable. Two indolent cases manifested as recurrent palpitation over 7 (case 21) and 9 years (case 20), respectively. On the other hand, the most violent case was a 41 year-old woman (case 17), who had been healthy complained of epigastric discomfort during breakfast, and, developed cardiac arrest immediately after as the initial manifestation.

The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 37±11%. Among 21 patients of the study group, 15 patients (71%) showed type 1 echocardiographic features. In patients who had received PM implantation, echocardiographic type I finding was more predominant than in those with ICD {92.8% (13/14) vs. 28.6% (2/7), p≤0.01}. Coronary angiography was performed in 15 patients, which revealed normal findings. In 12 patients, thallium-201 scintigraphy was conducted and abnormal perfusion was noted in 10 cases. However, among them, with the exception of a patient who did not undergo coronary angiography, 9 patients revealed normal coronary angiographic findings.

Endomyocardial biopsy was attempted in 6 patients, but cardiac sarcoidosis was not demonstrated in any of these cases. Among them, one patient (case 14) subsequently underwent cardiac transplantation due to intractable heart failure, and non-caseating granuloma suggesting sarcoidosis was histologically proven on the extracted heart. In addition to this, 2 patients experienced sarcoidosis involvement of the lungs (case 12) and lymph nodes (case 10).

Although 21 patients showed characteristic echocardiographic findings suggestive of sarcoidosis, only 3 patients (14.3%) showed typical extracardiac involvement of sarcoidosis. Each of these patients (case 10, 12 and 21) revealed typical sarcoid involvement in the lungs, lymph nodes and liver, respectively.

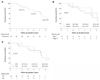

During follow-up (mean 75±18 months), various clinical events occurred. Nine patients (42.9%) had no adverse clinical events, whereas the other 12 patients needed hospital admission due to cardiac causes. Four patients suffered from bouts of aggravated heart failure, five arrhythmic event, one heart transplantation. Two patients died during follow-up (Table 1). Among them, 2 patients who had undergone PM implantation (case 11 and 12), developed VT 7 and 5 years later, respectively and eventually underwent ICD implantation. Three patients (case 1, 8 and 14) who had already received PM implantation subsequently developed atrial flutter, hence they underwent radiofrequency catheter ablation. In one patient with ICD for VT (case 16), repeated ICD discharge was not prevented with medication. So that he underwent catheter ablation. One patient underwent cardiac transplantation due to intractable heart failure (case 14), and two patients died during follow-up. The cause of death was heart failure (case 5) and gastrointestinal bleeding (case 4), respectively. The 1-, 2- 4-, and 6-year event-free survival rates were 100%, 85.7±7.6%, 75.0±9.7% and 48.6±12.4%, respectively (Fig. 4). The overall event-free survival rate was not different between patients with echocardiographic type I and those with type II (p=0.61). There was no significant difference in the event-free survival rate between the patients with PM and ICD (p=0.12).

The annual incidence of systemic sarcoidosis in the United States was reported to as approximately 20 per 100,000.11) In Korea, systemic sarcoidosis is also a rare disease but the incidence has gradually increased from 14 cases in 1993 (0.027 per 100,000) to 59 cases in 1998 (0.125 per 100,000).12) With regard to the prevalence of cardiac involvement, there is a significant racial difference. About 20-27% of systemic sarcoidosis patients presented with cardiac involvement in the United States, however the proportion was 58% in Japan.13) In one Korean study of 309 patients with pathologically proven systemic sarcoidosis, the prevalence of cardiac sarcoidosis was only 0.7%.12) We understand those reflect the difficulty in assessing cardiac involvement. According to the landmark report on cardiac sarcoidosis, which confirmed that most patients with cardiac sarcoidosis have little or no clinical evidence of extra-cardiac organ dysfunction,5) the current guideline for definitive diagnosis of sarcoidosis needs to be changed, especially for cardiac sarcoidosis. This is sensible, considering the low yield of endomyocardial biopsy.

The systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis are quite diverse. Occasionally, it first comes to attention when abnormalities are detected on a chest radiograph during routine screening. The majority of these patients are asymptomatic, whereas up to a third of patients have symptom related to organ impairment.14) Constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, night sweats, and weight loss are also common. Even in cases with cardiac involvement, the clinical manifestation is non-specific. It can manifest as cardiomyopathy with loss of muscle function, or tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias.15)16) Although the clinical manifestation of cardiac involvement is evident in less than 5% of patients with cardiac involvement, once the manifestation is clinically overt, it is the major cause of death together with neurologic involvement and pulmonary fibrosis.6)

In general, the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is established by histologic evidence in one or more organs with non-caseating epithelioid-cell granulomas.17) Pathologic specimens should be widely obtained where possible, such as the skin, peripheral lymph nodes, lacrimal glands, and the conjunctiva. According to one report, the diagnostic yield of transbronchial biopsy by means of bronchoscopy reached at least 85%, when multiple lung segments are sampled.18) Unfortunately, endomyocardial biopsy has a low diagnostic yield (less than 20%) because cardiac involvement tends to be patchy, and granulomas are more likely to be located in the left ventricle and in the basal ventricular septum, than in the right ventricle, where endomyocardial biopsies are usually performed.16) Failure to demonstrate histologic evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis in all 6 patients who underwent endomyocardial biopsy in our study represents the pitfalls of pathologic diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Although isolated cardiac involvement with sarcoidosis is known to be extremely rare (previously three cases were described by Nelson et al.19)), one peculiar observation in our study was that there were only 3 patients with extracardiac involvement, and the other 18 presented disease limited to the heart. In this context, pathologic confirmation from extracardiac organ was also challenging.

Patients with cardiac sarcoidosis showed very poor long-term event-free survival rates,20) which was confirmed again in our study. Different arrhythmias were observed during follow-up and ICD was necessary to manage VT in several patients during follow-up after PM insertion.

Considering the low yield of endomyocardial biopsy and rare systemic involvement in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, we need different approaches to diagnose high-risk patients, including those who underwent device treatment for arrhythmias. We believe that echocardiographic findings can be useful for this purpose in this selected group of patients, because characteristic basal septal thinning or aneurysmal dilatation can be regarded as supporting evidence of cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis.21) The clinical impact of cardiac sarcoidosis based on a combination of clinical features of significant arrhythmias warranting device therapy and characteristic echocardiographic findings needs to be evaluated in future investigations.

The main limitation of our study is that pathologic confirmation was not possible in all patients with characteristic echocardiographic findings. Although we ruled out the possibility of significant coronary artery disease as a cause of the characteristic wall motion abnormalities, we were not completely certain that other infiltrative or myocardial disorders resulted in these echocardiographic findings.22) The other limitation is that we selected patients with serious arrhythmias warranting device treatment, which significantly contributes to selection bias. Thus, the prevalence of characteristic echocardiographic findings in these selected patients does not necessarily represent the true prevalence of cardiac sarcoidosis.

In conclusion, in this observational study, we have found that some patients who received device therapy to control serious arrhythmias, including PM and ICD, showed characteristic echocardiographic features, such as thinning of basal septum or aneurysmal change without significant coronary artery disease, suggestive of cardiac sarcoidosis. These patients were characterized by very low endomyocardial biopsy yield and rare non-cardiac involvement. As these patients showed low event-free survival rates, combination of clinical features and characteristic echocardiographic findings can be considered a rational approach for tentative diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. The impact of this practical approach needs to be evaluated in future studies.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Representative echocardiographic images suggestive of cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis. Type 1 morphologic change is characterized by thinning and akinesia of the basal septum (A and B). Aneurysmal dilatation involving inferior or posterolateral wall is classified as type 2 (C and D).

Fig. 2

(A) and (C) are computed tomographic images of a 53-year old patient those demonstrate numerous enlarged lymph nodes compressing the adjacent structures. (B) is the echocardiographic image in which the arrow points at the basal septum with thinning. Panel D is a micrograph of a supraclavicular lymph node with non-caseating granuloma (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 200×; Scale bar=100 µm).

Fig. 3

A 44-year old man who had undergone pacemaker insertion 2 years before due to complete atrio-ventricular block complained of recurrent palpitation and dyspnea. He was diagnosed with atrial flutter and received radiofrequency catheter ablation. (A) Thereafter, thinning of basal septum became more prominent while symptoms of heart failure are more aggravated over the next 16 months. (C) denotes the echocardiography at the time of heart transplantation. (D) is a micrograph showing non-caseating granuloma from tricuspid valve of extracted heart (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 200×; Scale bar=100 µm).

Fig. 4

Event free survival of the overall group (A), and comparisons with those according to echocardiographic type (B), and the class of cardiac device inserted (C). Adverse clinical events included death, cardiac transplantation, and hospital admission due to cardiac causes during the follow-up period. ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, PM: pacemaker.

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of patients

*†Each patient No 4 and 5 died from gastrointestinal bleeding and intractable heart failure, respectively, ‡§∥Each patient No 10, 12 and 14 evidenced sarcoid granuloma on the specimen of SCLN, Lung and Heart, respectively. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, CAG: coronary angiography, SCLN: supraclavicular lymph node, RFCA: radio-frequency catheter ablation, ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, VT: ventricular tachycardia

References

1. Dubrey SW, Bell A, Mittal TK. Sarcoid heart disease. Postgrad Med J. 2007. 83:618–623.

2. Bargout R, Kelly RF. Sarcoid heart disease: clinical course and treatment. Int J Cardiol. 2004. 97:173–182.

3. Sekiguchi M, Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M. Cardiac sarcoidosis: diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic considerations. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1996. 10:495–510.

4. Lewin RF, Mor R, Spitzer S, Arditti A, Hellman C, Agmon J. Echocardiographic evaluation of patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Am Heart J. 1985. 110:116–122.

5. Roberts WC, McAllister HA Jr, Ferrans VJ. Sarcoidosis of the heart. A clinicopathologic study of 35 necropsy patients (group 1) and review of 78 previously described necropsy patients (group 11). Am J Med. 1977. 63:86–108.

6. Silverman KJ, Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Cardiac sarcoid: a clinicopathologic study of 84 unselected patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Circulation. 1978. 58:1204–1211.

7. Yamano T, Nakatani S. Cardiac sarcoidosis: what can we know from echocardiography? J Echocardiogr. 2007. 5:1–10.

8. Hiraga H, Yuwai K, Hiroe M. Guidelines for the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis: study report of diffuse pulmonary diseases. 1993. Tokyo: Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare;23–24.

9. Tawarahara K, Kurata C, Okayama K, Kobayashi A, Yamazaki N. Thallium-201 and gallium 67 single photon emission computed tomographic imaging in cardiac sarcoidosis. Am Heart J. 1992. 124:1383–1384.

10. Tellier P, Paycha F, Antony I, et al. Reversibility by dipyridamole of thallium-201 myocardial scan defects in patients with sarcoidosis. Am J Med. 1988. 85:189–193.

11. Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, Maliarik MJ, Iannuzzi MC. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997. 145:234–241.

12. Kim DS. Sarcoidosis in Korea: report of the Second Nationwide Survey. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2001. 18:176–180.

13. Matsui Y, Iwai K, Tachibana T, et al. Clinicopathological study of fatal myocardial sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976. 278:455–469.

14. Siltzbach LE, James DG, Neville E, et al. Course and prognosis of sarcoidosis around the world. Am J Med. 1974. 57:847–852.

15. Choi JH, Kim J, Park TI, et al. Two cases of an implantation of a permanent pacemaker using a transaxillary incision. Korean Circ J. 2008. 38:500–504.

16. Uemura A, Morimoto S, Hiramitsu S, Kato Y, Ito T, Hishida H. Histologic diagnostic rate of cardiac sarcoidosis: evaluation of endomyocardial biopsies. Am Heart J. 1999. 138:299–302.

17. Judson MA, Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Terrin ML, Yeager H Jr. Defining organ involvement in sarcoidosis: the ACCESS proposed instrument. ACCESS Research Group. A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999. 16:75–86.

18. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007. 357:2153–2165.

19. Nelson JE, Kirschner PA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis presenting as heart disease. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1996. 13:178–182.

20. Chiu CZ, Nakatani S, Zhang G, et al. Prevention of left ventricular remodeling by long-term corticosteroid therapy in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Am J Cardiol. 2005. 95:143–146.

21. Valantine H, McKenna WJ, Nihoyannopoulos P, et al. Sarcoidosis: a pattern of clinical and morphological presentation. Br Heart J. 1987. 57:256–263.

22. Cho Y. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Korean Circ J. 2008. 38:514–523.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download