Abstract

Background and Purpose

Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a syndrome of orthostatic intolerance in the setting of excessive tachycardia with orthostatic challenge, and these symptoms are relieved when recumbent. Apart from symptoms of orthostatic intolerance, there are many other comorbid conditions such as chronic headache, fibromyalgia, gastrointestinal disorders, and sleep disturbances. Dermatological manifestations of POTS are also common and range widely from livedo reticularis to Raynaud's phenomenon.

Methods

Questionnaires were distributed to 26 patients with POTS who presented to the neurology clinic. They were asked to report on various characteristics of dermatological symptoms, with their answers recorded on a Likert rating scale. Symptoms were considered positive if patients answered with "strongly agree" or "agree", and negative if they answered with "neutral", "strongly disagree", or "disagree".

Results

The most commonly reported symptom was rash (77%). Raynaud's phenomenon was reported by over half of the patients, and about a quarter of patients reported livedo reticularis. The rash was most commonly found on the arms, legs, and trunk. Some patients reported that the rash could spread, and was likely to be pruritic or painful. Very few reported worsening of symptoms on standing.

Conclusions

The results suggest that dermatological manifestations in POTS vary but are highly prevalent, and are therefore of important diagnostic and therapeutic significance for physicians and patients alike to gain a better understanding thereof. Further research exploring the underlying pathophysiology, incidence, and treatment strategies is necessary.

Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a syndrome of orthostatic intolerance that is most prevalent in young females.1 The hallmark of this disorder is an exaggerated increase in the heart rate (HR) in response to postural change, with relatively preserved autonomic reflexes.23 Contrary to the implication of its name, the symptoms and underlying pathophysiology of POTS are heterogeneous and are not restricted to orthostatic intolerance.4 Symptoms of POTS include inappropriate tachycardia, chronic fatigue, and dizziness. Symptoms that cannot be fully explained by orthostatic intolerance include gastrointestinal or bladder disorders, chronic headache, fibromyalgia, and sleep disturbances. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying POTS are also diverse and multifactorial, and include hypovolemia,5 hyperadrenergic states,6 lower-extremity neuropathies,7 and deconditioning.8

Dermatological manifestations are also frequently associated with POTS, and include (but are not limited to) Raynaud's phenomenon, erythromelalgia, livedo reticularis, hives, and varicose veins.910 The aim of the present study was to characterize the dermatological manifestations in a cohort of patients with POTS.

Patients with POTS were selected based on the results of tilt-table testing, in which this condition was established based on an HR increase of 30 beats/min or an HR of >120 beats/min within 10 minutes of tilt. A comprehensive survey was developed to assess the various symptoms experienced by patients with POTS. Fourteen questions of this survey were specific to dermatological symptoms. Patients at Boston Medical Center who met the diagnostic criteria for POTS were selected. Surveys were completed by 26 patients during 2014 and 2015. Responses were reported on the following 5-point Likert scale: strongly agree=5, agree=4, neutral=3, disagree=2, and strongly disagree=1. The frequency of positive responses (i.e., strongly agree and agree) and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated using Microsoft Excel; the other three responses (strongly disagree, disagree, and neutral) were considered negative responses.

Our IRB number is H-33658 and we are BUMC (Boston University Medical College) IRB exempt.

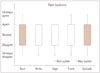

Twenty-two of the 26 patients (85%) reported at least 1 core dermatological symptom. Similarly, at least two dermatological symptoms were identified by slightly more than half (54%) of patients (Fig. 1A). The most commonly reported dermatological symptom was rash (77%); the strongest consensus was for presence of rash (median=4, IQR=0) (Fig. 1B). Most also agreed on the absence of varicose veins (median=2, IQR=2) and that symptoms did not change with position (median=2, IQR=1.5) (Fig. 2). Raynaud's phenomenon and hives were reported in nearly half (48%) and in a quarter (25%) of the patients, respectively. Itching was a common feature (54%; median=4, IQR=2), and the use of antihistamines did not ameliorate the rash (median=3, IQR=2.5). Most reported that the symptoms did not worsen with stress (median=2, IQR=2) or associated pain (median=2, IQR=2). Nearly a quarter of patients (23%) reported spreading of the rash, most commonly to the arms (50%) and trunk (48%), followed by the legs (42%) and the face (29%) (Fig. 3).

Our data suggest that there is a strong association between POTS and various dermatological complaints. Most of the patients reported at least two dermatological symptoms (Fig. 1B). The prevalence of Raynaud's phenomenon (48%) in this cohort exceeds the reported estimates in the population, which are currently up to 20%.1112 In addition, another study found that Raynaud's-like symptoms occurred alongside POTS in 74.1% of a pediatric cohort.9 Stewart et al.131415 proposed that Raynaud's phenomenon in POTS can be explained partially by excessive vasoconstriction and hypoxia in the cutaneous vasculature secondary to imbalances in local mediators, especially increased angiotensin II and decreased nitrous oxide. In fact, a recent study involved a case of moderate-to-severe POTS with dermatological manifestations including Raynaud's phenomenon that was successfully treated with losartan, which is a competitive angiotensin II receptor type I antagonist.10

The reported prevalence of hives (25%) in the present cohort greatly exceeds the reported estimate of 1% in the general population.16 In the unified model of POTS and mast cell activation syndrome, excessive vasodilatation caused by mast cell degranulation leads to increased sympathetic activity leading to orthostatic tachycardia. The increased sympathetic drive in turn leads to more mast cell activation, propagating the cascade.17 Thus, the available data suggest a role of dysfunctional hyperadrenergic system in both Raynaud's phenomenon and hives in addition to POTS.6

The first-line pharmacological management of pruritic dermatological conditions attributed to mast cell system activation involves H1 antihistamines.18 Twenty-five percent of our patients reported symptoms of hives and 54% reported pruritus associated with the rash. Interestingly, most of the patients with rash reported that it was not ameliorated by antihistamine treatment (Fig. 2). "Rash" could be interpreted as either an umbrella term that encompasses the other three dermatological symptoms in question (i.e., hives, Raynaud's phenomenon, and varicose veins), or it could be interpreted as a separate dermatological entity such as erythromelalgia or livedo reticularis. Furthermore, studies on the rare disease of adrenergic hives (or adrenergic urticaria) have suggested that activation of adrenergic receptors can lead to direct mast-cell activation without histamine liberation.1920

Neuropathic POTS specifically describes a subgroup of POTS with evidence of peripheral sympathetic denervation, resulting in venous pooling in the lower limbs.7 It was previously reported that factors that augment venous pooling, such as varicose veins, are associated with orthostatic symptoms even in otherwise healthy patients.21 In fact, midodrine, which is commonly used to treat symptoms associated with POTS, acts primarily by reducing venous pooling.4 Interestingly, whereas one-third of the population worldwide is estimated to be affected by varicose veins,22 this feature was reported by only 13% of the present cohort. While rash is found on the arms, legs, and trunk, it is less commonly found on the face and it rarely spreads (Fig. 3). In addition, patients report that there is no change in the rash when the position changes, which is an important orthostatic stressor, especially in POTS. This further supports the notion that POTS is not a nosological disease and that there are many symptoms that cannot be explained by orthostatic intolerance alone.4

The limitations of this study include the small sample size and the lack of comparison with a control group. Studies with larger patient samples will enable differentiation between high- and low-frequency symptoms. In addition, the intake survey has not yet been validated. Additional information on each symptom would be useful in terms of symptomatic treatment, but also for elucidating the pathophysiology.

POTS, a common form of orthostatic intolerance, remains poorly understood. This analysis of 26 patients at a large medical center was conducted in order to obtain a better understanding of the dermatological presentations of POTS patients. The results suggest that dermatological presentations in POTS patients vary, but are highly prevalent, and may therefore be of important diagnostic and therapeutic significance for physicians and patients alike. Further research exploring the underlying pathophysiology, incidence, and treatment strategies for this condition are necessary.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Response rates for core dermatological symptoms. A: Bar graph displays the frequency of positive responses (i.e., "strongly agree" or "agree"). B: Box-and-whisker plots display the median and interquartile range for each symptom. Q1: first quartile, Q3: third quartile. |

References

1. Stewart JM. Pooling in chronic orthostatic intolerance: arterial vasoconstrictive but not venous compliance defects. Circulation. 2002; 105:2274–2281.

2. Schondorf R, Low PA. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: an attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia? Neurology. 1993; 43:132–137.

3. Low PA, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Textor SC, Schondorf R, Suarez GA, Fealey RD, et al. Comparison of the postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) with orthostatic hypotension due to autonomic failure. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1994; 50:181–188.

4. Benarroch EE. Postural tachycardia syndrome: a heterogeneous and multifactorial disorder. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012; 87:1214–1225.

5. Raj SR, Robertson D. Blood volume perturbations in the postural tachycardia syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2007; 334:57–60.

6. Jordan J, Shannon JR, Diedrich A, Black BK, Robertson D. Increased sympathetic activation in idiopathic orthostatic intolerance: role of systemic adrenoreceptor sensitivity. Hypertension. 2002; 39:173–178.

7. Jacob G, Costa F, Shannon JR, Robertson RM, Wathen M, Stein M, et al. The neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343:1008–1014.

8. Joyner MJ, Masuki S. POTS versus deconditioning: the same or different? Clin Auton Res. 2008; 18:300–307.

9. Ojha A, Chelimsky TC, Chelimsky G. Comorbidities in pediatric patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Pediatr. 2011; 158:20–23.

10. Landero J. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: a dermatologic perspective and successful treatment with losartan. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014; 7:41–47.

11. Suter LG, Murabito JM, Felson DT, Fraenkel L. The incidence and natural history of Raynaud's phenomenon in the community. Arthritis Rheum. 2005; 52:1259–1263.

12. Maricq HR, Carpentier PH, Weinrich MC, Keil JE, Franco A, Drouet P, et al. Geographic variation in the prevalence of Raynaud's phenomenon: Charleston, SC, USA, vs Tarentaise, Savoie, France. J Rheumatol. 1993; 20:70–76.

13. Stewart JM, Taneja I, Medow MS. Reduced body mass index is associated with increased angiotensin II in young women with postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007; 113:449–457.

14. Stewart JM, Taneja I, Glover J, Medow MS. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade corrects cutaneous nitric oxide deficit in postural tachycardia syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008; 294:H466–H473.

15. Stewart JM, Ocon AJ, Clarke D, Taneja I, Medow MS. Defects in cutaneous angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-(1-7) production in postural tachycardia syndrome. Hypertension. 2009; 53:767–774.

17. Shibao C, Arzubiaga C, Roberts LJ 2nd, Raj S, Black B, Harris P, et al. Hyperadrenergic postural tachycardia syndrome in mast cell activation disorders. Hypertension. 2005; 45:385–390.

18. Sharma M, Bennett C, Cohen SN, Carter B. H1-antihistamines for chronic spontaneous urticaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 11:CD006137.

19. Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Adrenergic urticaria: a new form of stress-induced hives. Lancet. 1985; 2:1031–1033.

20. Haustein UF. Adrenergic urticaria and adrenergic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990; 70:82–84.

21. Chapman EM, Asmussen E. On the occurrence of dyspnea, dizziness and precordial distress ccasioned by the pooling of blood in varicose veins. J Clin Invest. 1942; 21:393–399.

22. National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Varicose Veins in the Legs: The Diagnosis and Management of Varicose Veins. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK);2013.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download