Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to describe the implementation of single visit approach or See-visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid (VIA)-and Treat-immediate cryotherapy in the VIA positive cases-model for the cervical cancer prevention in Jakarta, Indonesia.

Methods

An observational study in community setting for See and Treat program was conducted in Jakarta from 2007 until 2010. The program used a proactive and coordinative with VIA and cryotherapy (Proactive-VO) model with comprehensive approach that consists of five pillars 1) area preparation, 2) training, 3) awareness, 4) VIA and cryotherapy, and 5) referral.

Results

There were 2,216 people trained, consist of 641 general practitioners, 678 midwives, 610 public health cadres and 287 key people from the society. They were trained for five days followed by refreshing and evaluation program to ensure the quality of the test providers. In total, 22,989 women had been screened. The VIA test-positive rate was 4.21% (970/22,989). In this positive group, immediate cryotherapy was performed in 654 women (67.4%).

Cervical cancer is the seventh in frequency overall, but it ranked for the second highest cancer in worldwide among women next only to breast cancer and is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the developing countries [1]. Cervical cancer continues to be a widespread public health problem in women throughout the world, especially in developing country like Indonesia [2]. The data from thirteen pathology centers in Indonesia shows that cervical cancer stands the first-ranked among all cancer (23.43% from 10 most common cancers among men and women; 31.0% from 10 most common cancers among women) [3]. Data from various academic hospitals in 2007 showed that cervical cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy followed by cancers of the ovary, uterus, vulva, and vagina [4].

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is a causative agent of cervical cancer, one study in Indonesia has shown that HPV was detected 96% in cervical cancer patients; HPV 16 and HPV 18 were found in 83% [4]. Since it is known that HPV has a strong relation to cervical cancer, ideally HPV vaccines are the choice in cervical cancer prevention programs. However, in developing countries, a limitation in cost becomes a big issue and therefore a vaccination program is not applicable yet. Thus preventing cervical cancer is still focused on the screening program.

The screening program itself has its own limitations. 'The lack of effective screening and treatment' program is the main reason why the rate of cervical cancer is higher in developing countries. Other common problems in women from the middle low class is that they generally seek care only when they develop symptoms and by that time the cancer has advanced and is difficult to treat. Approximately 70% are in the advanced stage when they come to the hospital (≥ stage IIB) [5], and at these stages, cancer has infiltrated the parametrium. Despite a complete effective treatment, the result will not be satisfactory and with ensuing higher mortality rate [5]. Moreover, even if women seek for help, some of them do not return to obtain test results or receive treatment.

By the introduction of regular screening with the Pap smear, the incidence and mortality rates for cervical cancer have declined to 70-80% and 90%, respectively, in most developed countries [6,7]. Nevertheless there are still many obstacles to make Pap smear the basic method of screening programs in developing countries like Indonesia, especially the limitations of pathologist which is very important for diagnosis. There are only 292 pathologists (data from IAPI 2010) [8] which must serve the population of Indonesia that numbers 237 million of people (Statistic Centre at Republic of Indonesia 2010) [9]. To address this health inequity, it is necessary to have an alternative method. Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) was identified as the potentially optimal alternative technique to use in a setting with low resources for its high sensitivity and specificity. According to the University of Zimbabwe Jhpiego [10], with lesion degree of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) and more severe, Sankaranarayanan et al. [11] in India with moderate/severe dysplasia and more severe lesion degree revealed that the sensitivity and specificity was 77% for sensitivity and 64% for specificity [10]; 90% for sensitivity and 92% for specificity, respectively [11].

VIA is a relatively noninvasive, inexpensive and can also be provided at all levels of the healthcare system by nurses and midwives because it is simple and easy to perform. Other advantages of VIA testing over cytology based (Pap smear) services is that the results are immediately available. This means that the further decisions can be made during a woman's initial visit such as treatment by cryotherapy. That's why the program is called by See and Treat program.

To conquer the problem of cervical cancer it needs a couple of activities that is starting with a preparation of the area, training of midwives and health cadres, socialization and education for the community by 'PKK (Pendidikan Kesejahteraan Keluarga-Family Welfare Women Organization)' as health cadres. Then it followed by the implementation phase of screening with VIA and cryotherapy as the treatment on the findings of a positive VIA. It is named as Proactive-VO model that is proactive and well coordinated with the screening method of VIA, which empowers midwives and cryotherapy as the treatment in a single visit.

Research design is an observational study in community setting for cervical cancer prevention coordinated by the Female Cancer Program (FCP) under Faculty of Medicine of the University of Indonesia-Ciptomangunkusumo General Hospital. This study was conducted in Jakarta from 2007 up until 2010. We combined the See and Treat model and how to implement in the community in a comprehensive approach, which consists of five pillars of foundation 1) area preparation that was coordinated with local government, 2) training course involving VIA and cryotherapy, 3) awareness, 4) screening and treat by VIA and cryotherapy, and 5) referral system of the difficult cases where there was a possibility of invasive disease. All of the activities formulated in a model, which called Proactive-VO model, as express in the schema (Fig. 1).

In this model, we should have the same program goal: 1) Increasing the screening coverage up to 70-80%, 2) having vaccination coverage, 3) increasing the finding of precancerous lesion, 4) reducing the advance stage of cervical cancer, 5) reducing the mortality rate of cervical cancer.

The training consist of five days that include 2 days of basic theory and dry workshop, 1 day of live demonstration and 2 days of working at their own clinic or Public Health Centre. All these examinations were undersupervised. The goal of the training was to achieve the level of competence. This level of competence will be achieved if they had examined 100 of patients from which there were two or three patients that had a positive-tested VIA predicted. The positive-tested VIA were confirmed by the supervisor. After the training, we conduct another refreshing and evaluation program the following 3 months to ensure the quality assurance of the test providers.

The awareness was done by health cadres, general practitioners and midwives using education materials such as leaflets and flipcharts. Leaflets were distributed door to door to motivate women in the area to go to the nearest Public Health Centre 'Puskesmas' in order to participate in the See and Treat program.

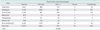

From 2007 up until 2010, there were 22,989 women who underwent VIA testing, except those with history of cervical cancer, history of total hysterectomy and pregnant women with less than 20 weeks of gestational age by clinical examination. The clients were positioned on the examination table, and then the speculum inserted in order to view the cervix. After that the cervix was assessed as to whether or not there was a presence of gross lesions consistent with possible cancer. Special attention was paid to ensuring that the entire squamo-columnar junction was visualized. The next step was to swab the cervix with 3-5% of acetic acid solution then the cervix was re-examined by an examination light. VIA was said to be positive value if there was a raised and thickened white plaques on the clinical findings (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Women with VIA positive-tested were offered to have an immediate therapy (cryotherapy), which involved freezing an area of abnormal tissue on the cervix by placing freeze-probe (cryoprobe) that covered the cervix which cools the cervix to sub-zero temperatures, using N2O or CO2. This abnormal tissue gradually disappears and the cervix heals. The main advantage of cryotherapy is that it is a simple procedure that requires inexpensive equipment that is suitable for low resource setting area. Most importantly, since the cryotherapy was offered immediately, it can reduce the loss to follow-up and the loss of opportunity to treat.

During this period based on area preparation as the first pillar, communication was developed with two Health Offices Districts, which are situated in Central of Jakarta and East of Jakarta. After the communication had been developed, the program area was setup at the Public Health Centre.

The second pillar is the training management which had been held for five days. There were 2,216 people trained which consisted of 641 general practitioners, 678 midwives, 610 public health cadres and 287 'key person' from the society (Table 2).

The third pillar is conducting awareness in order to motivate women at the area to go to the Public Health Centre 'Puskesmas' for participating in the See and Treat program. The awareness was provided to 80,991 women.

The fourth pillar is screening and treating by VIA and cryotherapy. During the end of 2007 to 2010, there were 22,989 clients that had been screened. The VIA test-positive rate was 4.21% (970/22,989) and 67.42% (654/970) of those eligible accepted immediate treatment. From 22,989 respondents, 19 cases (0.08 %) of invasive cervical cancer were found (Table 3).

The fifth pillar is the 'referral system' for those where there was a possibility of invasive disease. They were reconfirmed by histopathology examination.

The fact that 80% of all cervical cancer cases and deaths occur in less-developed countries, this is mainly due to the absence of well-organized screening programs. Thus, in the period of 2007 until 2010, the See and Treat program screened 22,989 correspondents, of which 4.21% (970) were VIA-test positive.

Cervical cancer usually proceeds by cytological changes, known as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and it takes a long period of 15-20 years before the invasive cancer develops [12,13]. Pap smear programs, also known as cytology-based screening programs, have achieved impressive results in reducing cervical cancer incidence and mortality in some developed countries that have the infrastructure to support these programs [14]. Nevertheless, cytology-based screening programs have proven difficult to implement and sustain in low-resource settings. High-quality cytology laboratories are difficult to maintain and there are often substantial delays before the results become available [15]. In developed countries, women with abnormal cytological results are usually referred for colposcopy with biopsy before initiating treatment [16]. Colposcopy services and histopathologic laboratories are often not available in low-resource settings. Other obstacles that makes Pap smear difficult to be implemented is the limitations of pathologist which is very important for diagnosis. There are only 292 pathologist in all of Indonesia (Indonesian Patologist Centre-IAPI), who must serve the population of Indonesia that numbers to 237 million of people [9].

Thus Proactive-VO (proactive and well coordinated with VIA and cryotherapy) model is being introduced in detecting early stage of cervical cancer with VIA and direct treatment with cryotherapy. Research has established the viability of VIA to identify precancerous lesions [10,11,17-23]. Acetic acid causes dehydration of the cells and some surface coagulation of cellular proteins, thereby reducing the transparency of the epithelium. These changes are more pronounced in abnormal epithelium due to a higher nuclear density and consequent high concentration of protein. It is possible to recognize the white plaque of the cervical epithelium with a naked eye, and this constitutes a positive VIA test (Fig. 2). In the screening, VIA test-positive was 4.21%, which is similar to the findings of Nuranna in 2003-2004 (2.16%). Besides its high sensitivity and low-cost as it does not require a laboratory infrastructure [24], VIA is simple enough for midwives to provide at low levels of the health-care system, with locally available supplies.

Women in many developing countries, particularly women in rural areas, have limited access to health services due to living long distances from health centers, transportation costs, family and work responsibilities, and other barriers. In developing countries, the proportion of women who do not return for treatment after screening can be as high as 80%, which severely jeopardizes the effectiveness of a cervical cancer prevention program [25,26]. VIA test provides an immediate result, therefore loss to follow-up is kept to a minimum [27-29].

Cervical cancer can be prevented if timely identification of precancerous lesions is followed by an effective treatment. In this case, cryotherapy was selected as the immediate treatment because it has a cure rate comparable to other common outpatient procedures [30-32] which provides a high cure rate for CIN I and CIN II, whereas for CIN III the result might not be as good as CIN I/II. Cervical cryotherapy is used widely not only because of its proven efficacy but also it is easily learned, does not require electricity and can be performed in the outpatient (office setting) without the use of local or general anesthesia and requires inexpensive equipment [33]. Cryotherapy also has a documented history of low complication rates [31,32,34].

One of the most common disadvantages of cryotherapy is profuse watery discharge that persists for up to 6 weeks. Therefore, it is important to provide post treatment counseling about temporary abstinence from sexual intercourse for approximately 4 weeks [35]. Due the culture of Indonesian society, wives have to ask for approval in advance from their husbands in making the treatment decision. Therefore it explains the differences in percentage of cryotherapied women from area to area.

VIA is an appropriate alternative screening method as it is applicable, affordable, accessible, and acceptable; and cryotherapy is a promising way to treat precancerous lesions in this low resource setting. This Proactive-VO model is recommended for cervical cancer prevention.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The model with 5 Pillars applicate at the Jakarta field. FCP, female cancer program; HOGI, Himpunan Onkologi Ginekologi Indonesia; VIA-CRYO, visual inspection with acetic acid and cryotherapy; YKI, Yayasan Kanker Indonesia.

Fig. 2

Positive result (acetowhite lesion) of visual inspection after the application of acetic acid.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank you Female Cancer Program International and Faculty of Medicine University of Leiden, The Netherlands as well as Indonesian Cancer Foundation (YKI) for supporting this program.

References

1. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Globocan 2008 fast stats [Internet]. 2010. cited 2012 Jun 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer;Available from:

http://globocan.iarc.fr/factsheets/populations/factsheet.asp?uno=900.

2. World Health Organization. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: report of a WHO consultation [Internet]. 2002. cited 2011 Aug 8. Geneva: World Health Organization;Available from:

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2002/9241545720.pdf.

3. Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. Indonesian Pathology Association. The Indonesian Cancer Foundation. Histopathological data of cancer in Indonesia 2006. 2006. Jakarta: Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia.

4. Aziz MF. Gynecological cancer in Indonesia. J Gynecol Oncol. 2009. 20:8–10.

5. Anggraeni TD, Nuranna L, Catherine C, Sobur CS, Rahardja F, Hia CW, et al. Distribution of age, stage, and histopathology of cervical cancer: a retrospective study on patients at Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia, 2006-2010. Indones J Obstet Gynecol. 2011. 35:21–24.

6. Anttila A, Nieminen P, Hakama M. Prendiville W, Davies P, editors. Cervical cytology as a screening test. HPV handbook. 2004. London: Taylor & Francis;11–23.

7. Sasieni P, Castanon A, Cuzick J. Effectiveness of cervical screening with age: population based case-control study of prospectively recorded data. BMJ. 2009. 339:b2968.

8. Association of Pathology Indonesia (IAPI) [Internet]. c2010. cited 2012 Jun 11. Jakarta, Indonesia: IAPI;Available from:

http://iapindonesia.com.

9. Budan Pusat Statistik Republik Indonesia. Budan Pusat Statistik [Internet]. c2009. cited 2012 Jun 11. Jakarta, Indonesia: Budan Pusat Statistik Republik Indonesia;Available from:

http://dds.bps.go.id/eng/.

10. Visual inspection with acetic acid for cervical-cancer screening: test qualities in a primary-care setting - University of Zimbabwe/JHPIEGO Cervical Cancer Project. Lancet. 1999. 353:869–873.

11. Sankaranarayanan R, Wesley R, Somanathan T, Dhakad N, Shyamalakumary B, Amma NS, et al. Visual inspection of the uterine cervix after the application of acetic acid in the detection of cervical carcinoma and its precursors. Cancer. 1998. 83:2150–2156.

12. Sankaranarayanan R, Wesley RS. A practical manual on visual screening for cervical neoplasia. 2003. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Center.

13. Sellors JW, Sankaranarayanan R. Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial Neoplasia: a beginner's manual. 2003. Lion, France: International Agency for Research on Center Press.

14. Miller AB. Cervical cancer screening programmes: managerial guidelines. 1992. Geneva: World Health Organization.

15. Richart RM. Screening: the next century. Cancer. 1995. 76:1919–1927.

16. Wright TC Jr, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB, Wilkinson EJ. ASCCP-Sponsored Consensus Conference. 2001 Consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA. 2002. 287:2120–2129.

17. Sankaranarayanan R, Shyamalakumary B, Wesley R, Sreedevi Amma N, Parkin DM, Nair MK. Visual inspection with acetic acid in the early detection of cervical cancer and precursors. Int J Cancer. 1999. 80:161–163.

18. Belinson JL, Pretorius RG, Zhang WH, Wu LY, Qiao YL, Elson P. Cervical cancer screening by simple visual inspection after acetic acid. Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 98:441–444.

19. Cecchini S, Bonardi R, Mazzotta A, Grazzini G, Iossa A, Ciatto S. Testing cervicography and cervicoscopy as screening tests for cervical cancer. Tumori. 1993. 79:22–25.

20. Megevand E, Denny L, Dehaeck K, Soeters R, Bloch B. Acetic acid visualization of the cervix: an alternative to cytologic screening. Obstet Gynecol. 1996. 88:383–386.

21. Londhe M, George SS, Seshadri L. Detection of CIN by naked eye visualization after application of acetic acid. Indian J Cancer. 1997. 34:88–91.

22. Mandelblatt JS, Lawrence WF, Gaffikin L, Limpahayom KK, Lumbiganon P, Warakamin S, et al. Costs and benefits of different strategies to screen for cervical cancer in less-developed countries. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002. 94:1469–1483.

23. Kitchener HC, Symonds P. Detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in developing countries. Lancet. 1999. 353:856–857.

24. Goldie SJ, Kuhn L, Denny L, Pollack A, Wright TC. Policy analysis of cervical cancer screening strategies in low-resource settings: clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness. JAMA. 2001. 285:3107–3115.

25. Bolivia Ministry of Health, EngenderHealth, Pan American Health. Cervical cancer prevention and treatment services in Bolivia: a strategic assessment. 2003. New York: Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention.

26. Gage JC, Ferreccio C, Gonzales M, Arroyo R, Huivin M, Robles SC. Follow-up care of women with an abnormal cytology in a low-resource setting. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003. 27:466–471.

27. Herdman C, Sherris J. Planning appropriate cervical cancer prevention programs. 2000. 2nd ed. Seatle, WA: PATH Publications.

28. Abwao S, Greene P, Sanghvi H, Tsu V, Winkler JL. Prevention and control of cervical cancer in the east and southern Africa region. 1998. Seatle, WA: PATH Publications.

29. Santos C, Galdos R, Alvarez M, Velarde C, Barriga O, Dyer R, et al. One-session management of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a solution for developing countries. A prospective, randomized trial of LEEP versus laser excisional conization. Gynecol Oncol. 1996. 61:11–15.

30. Mitchell MF, Tortolero-Luna G, Cook E, Whittaker L, Rhodes-Morris H, Silva E. A randomized clinical trial of cryotherapy, laser vaporization, and loop electrosurgical excision for treatment of squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix. Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 92:737–744.

31. Nuovo J, Melnikow J, Willan AR, Chan BK. Treatment outcomes for squamous intraepithelial lesions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2000. 68:25–33.

32. Andersen ES, Husth M. Cryosurgery for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 10-year follow-up. Gynecol Oncol. 1992. 45:240–242.

33. Morris DL, McLean CH, Bishop SL, Harlow KC. A comparison of the evaluation and treatment of cervical dysplasia by gynecologists and nurse practitioners. Nurse Pract. 1998. 23:101–102. 108–110. 113–114.

34. Cox JT. Management of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Lancet. 1999. 353:857–859.

35. Jacob M, Broekhuizen FF, Castro W, Sellors J. Experience using cryotherapy for treatment of cervical precancerous lesions in low-resource settings. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005. 89:Suppl 2. S13–S20.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download